For the first 10 years that Michelle Eisen worked as a Starbucks barista in Buffalo, N.Y., it never occurred to her to form a union. But the COVID-19 pandemic changed everything—including her opinion of the company she had long admired.

“We were tired and we were scared,” Eisen said at a Brookings event last week. “And we were feeling incredibly undervalued and unappreciated.”

Eisen contrasted the sacrifices and struggles that she and her colleagues endured with her employer’s financial success—a sentiment we heard echoed across dozens of interviews with frontline workers since the start of the pandemic.

“We are being called ‘essential workers’ and we are putting our health and safety at risk to work through this pandemic,” said Eisen. “And we’re hearing our CEO on CNN and other financial shows announce these record-breaking profits…And I know that this money is coming from my labor and my coworkers’ labor. I’ve got co-workers who are crying in the back room because they don’t know if they’re going to be able to pay their rent and put groceries in their fridge that week.”

In summer 2021, on the brink of quitting, Eisen instead joined her colleagues in filing to form Starbucks’ first-ever union. Their successful vote that December sparked a nationwide movement that now counts over 50 victories, including several successful votes this week alone. Since August 2021, workers at more than 200 additional Starbucks locations have petitioned to hold union elections.

Starbucks workers are not outliers in seeking union representation. Between October 2021 and March 2022, the number of union petitions filed with the National Labor Relations Board increased by 57%—a dramatic jump after decades of declining union membership. Among the petitions filed last October was that of the fledgling Amazon Labor Union, led by Chris Smalls, which made headlines last month with their upset victory in a Staten Island, N.Y. Amazon warehouse.

This surging demand for union representation should come as no surprise. The findings of our new report, Profits and the pandemic: As shareholder wealth soared, workers were left behind, help explain why. Alongside co-author Katie Bach, we analyzed how 22 leading companies—including Starbucks and Amazon—shared their pandemic profits and financial gains with workers. We looked precisely at the period between January 2020 and October 2021, which immediately preceded the spike in union petition filings, including those at Amazon and Starbucks.

Our report found that wealthy shareholders, executives, and billionaire heirs and founders were the pandemic economy’s real winners, while frontline workers benefited minimally from their employer’s success. Despite the potential moment for change the pandemic presented, on average, the 22 companies we analyzed are paying workers only modestly more in real terms than they did before COVID-19—and, for most workers, still not enough to get by.

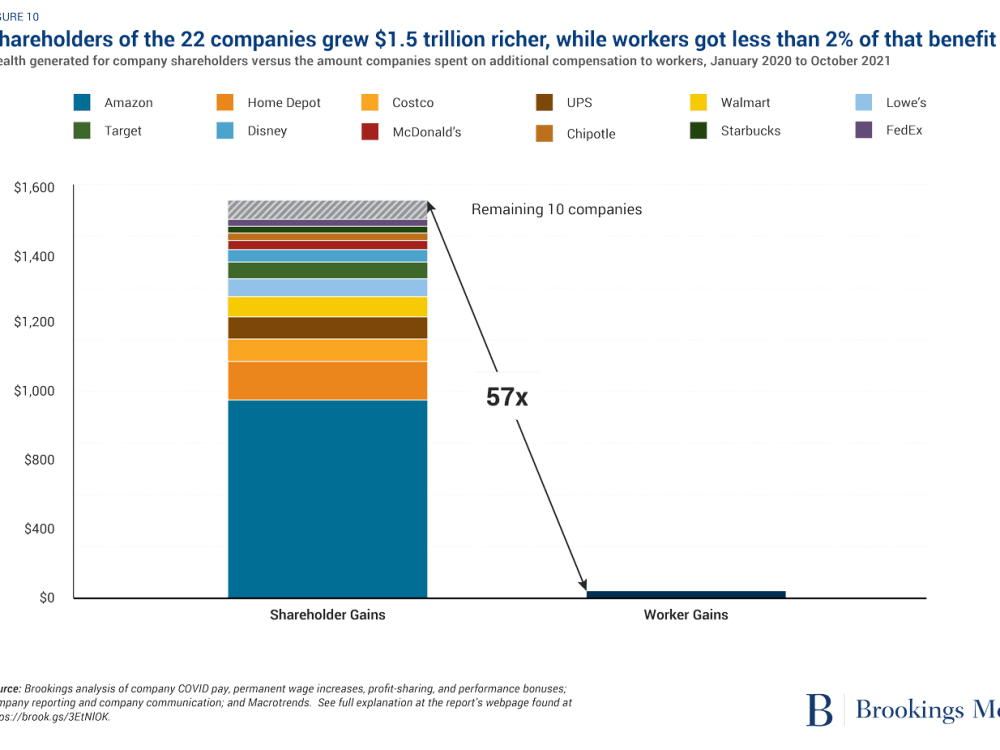

Between January 2020 and October 2021, the shareholders of these 22 companies grew $1.5 trillion richer, while their 7 million workers received $27 billion in additional pay—less than 2% of shareholders’ gains. At Amazon alone, the wealth the company generated for its shareholders through October 2021 was 177 times greater than the additional pay given to the company’s more than 1 million frontline employees.

Most of these financial gains accrued to already wealthy households. More than 70% of the wealth these 22 companies generated for U.S. shareholders during the pandemic benefitted the richest 5% of Americans, compared to just 1% for the bottom half of all American families, including most frontline workers.

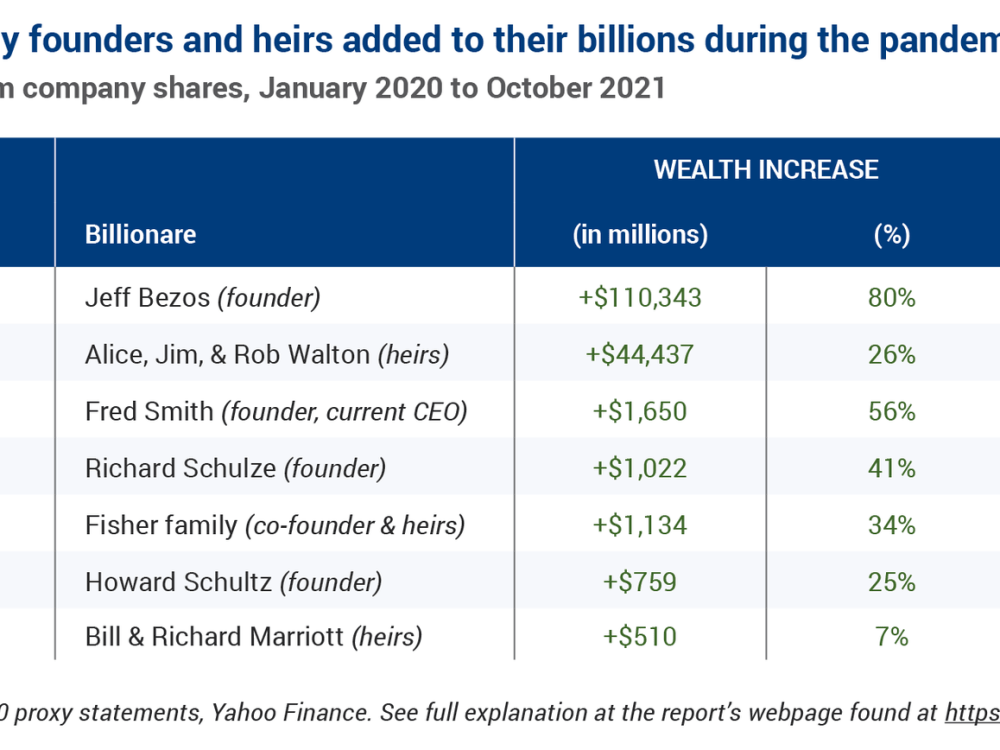

Billionaire founders and heirs were among those that gained the most. At seven of the 22 companies, including Starbucks and Amazon, the wealth of 13 billionaire founders and heirs would have grown by nearly $160 billion in the first 22 months of the pandemic—more than 12 times all extra pay to the 3.4 million U.S. workers those companies employed. Through October 2021, the value of founder Jeff Bezos’ Amazon shares rose by $110 billion, while founder and current CEO Howard Schultz’s Starbucks shares increased by more than $750 million. (These wealth gains are lower today due to recent drops in company share prices.)

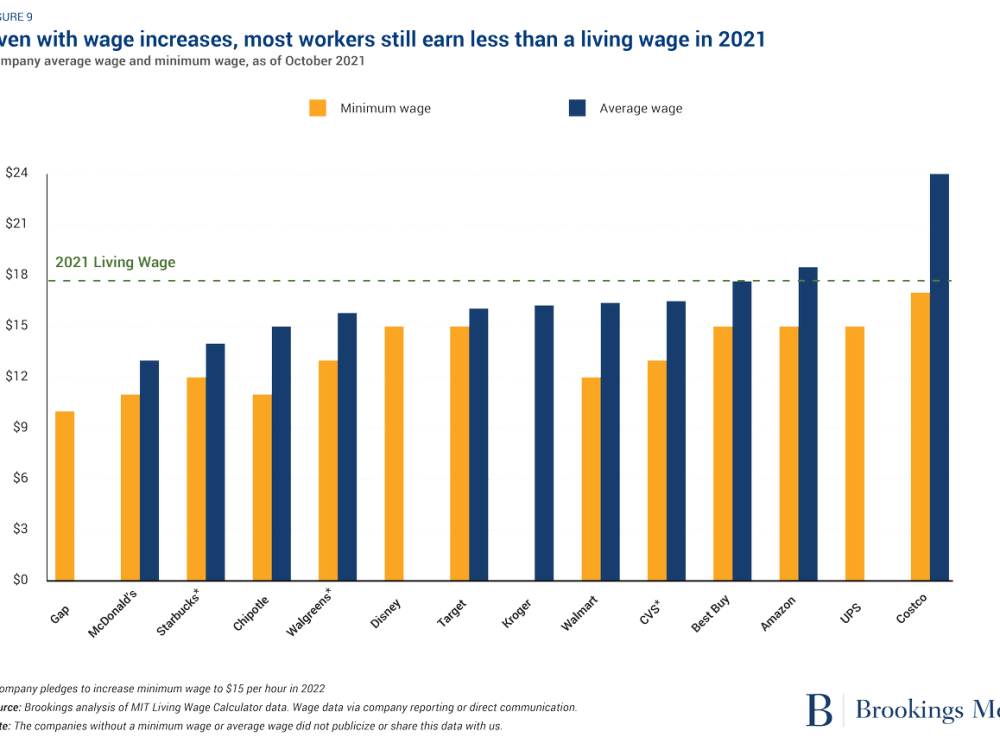

While most companies, including Amazon and Starbucks, raised wages during the pandemic, workers’ real gains were modest. Due to a combination of high inflation and a very low wage starting point, the vast majority of workers still earn too little to get by. At most, only seven of the 22 companies are paying at least half of their workers a living wage—enough to cover just their basic expenses. Only one company, Costco, has a minimum wage today that is close to a living wage.

We estimate that across all 22 companies, the average real wage gain, factoring in inflation, was between 2% and 5% through October 2021. Unless these companies raised wages substantially since then, fast-rising inflation would have eroded most, or even all, of these gains.

Take Amazon. Faced with high employee turnover and booming business, Amazon hired hundreds of thousands of new warehouse workers since the start of the pandemic and raised its average hourly wage from $15.75 to $18.50—a 17% nominal increase, the highest of the companies we analyzed. Yet inflation has erased the vast majority of these gains; adjusted for inflation, Amazon’s average wage was up 10% through October 2021, and just 5% through March of this year—less than $1 per hour. The company’s $15 minimum wage has lost more than $1.50 in purchasing power.

Starbucks also raised wages during the pandemic. Despite these increases, the majority of Starbucks workers still earn too little today to get by. As of October 2021, the company’s minimum wage was $12 per hour and its average wage was $14 per hour. In December, two days after Michelle Eisen and her Buffalo colleagues voted to become the first unionized Starbucks in the country, the company pledged to raise wages again by this summer to a minimum of $15 per hour and an average of $17 per hour—still less than a living wage that would allow its workers to pay their basic expenses.

Against the backdrop of these lopsided corporate gains and worker struggles, the appeal of unions is clear. Historically, unions have served as one of the most important counterweights to shareholder and corporate power by curbing inequality, moderating excess profits, and securing wage gains for workers.

This newfound union power was evidenced this week. Faced with a rapidly expanding unionization drive, Starbucks CEO Howard Schultz announced $1 billion in planned investments in worker wages and benefits this fiscal year. Schultz clarified that these new benefits and pay would only be available for non-union stores—a potentially illegal exclusion that illustrates the aggressive tactics companies deploy to thwart unionization efforts. Notably, the company’s announcement reflects many of the same demands that Starbucks union members have sought from the company, including pay raises for workers with longer tenures and the introduction of tipping.

“I’ve always said we need a voice within the business,” Michelle Eisen said at last week’s Brookings event. “And the voice would allow us to be a part of those decisions, which would decide wages, which would decide benefits, which would decide stock buybacks. Just being able to have a conversation with someone who essentially makes those decisions and then be able to vote on those decisions for yourself and your location, that’s what we need. There has to be a conversation.”

Ultimately, equitable gains for workers will only happen with a new balance of power between workers, companies, and shareholders. This rebalance will be fueled by the courage on display as an increasing number of workers exercise their right to organize. But it can’t stop with the bravery of workers like Michelle Eisen, Chris Smalls, and other leading union organizers who will meet with Vice President Kamala Harris at the White House this week. The U.S. needs major labor law reforms and legislative changes to give workers a more even playing field so they can exercise this power and have a real voice within their workplace.

Commentary

Frontline workers were excluded from companies’ pandemic windfalls. No wonder so many are forming unions.

May 4, 2022