In the face of dour news about stagnant wages, rising inequality, and a vanishing middle class, metropolitan areas are raising local minimum wages, experimenting with new apprenticeship programs, and considering a range of other development tools to tackle their workforce challenges. Collectively, these strategies represent crucial steps to boost incomes and improve economic mobility during the recovery. In the same way, infrastructure investment is supporting more and better jobs throughout the country, drawing from a variety of efforts across the public and private sector.

However, the federal transportation program is headed toward another financial cliff, and Washington is once again scrambling to find a patchwork solution for the crumbling roads, bridges, and facilities whose maintenance is central to economic growth. An oft-cited statistic, for instance, notes that every $1 billion in highway spending can directly and indirectly create up to 13,000 jobs a year. With continued uncertainty at the federal level, many states and localities are delaying construction projects and remain trapped in a cycle of deferred maintenance that hurts thousands of employers and workers alike.

The need to invest in U.S. infrastructure has never been clearer, making it all the more critical to take a fresh look at infrastructure’s importance to the labor market, both to drive long-lasting growth and to expand economic opportunity across the entire workforce—two elements often missing from the current narrative on infrastructure and jobs.

First, infrastructure is not limited to short-term construction. Beyond “shovel-ready” projects, millions of workers are critical to providing timely transportation, reliable water, efficient energy, and other public services over several decades. Engaged in the construction, operation, governance, and design of infrastructure, these workers—from bus drivers and civil engineers to air traffic controllers and telecommunication line installers—play a key role supporting the economy across every region.

Second, infrastructure jobs usually represent long-term, well-paid opportunities for the two-thirds of U.S. workers who lack four-year college degrees. These jobs not only boast competitive wages and have relatively low barriers to entry, but they also have enormous replacement needs, primarily due to an impending wave of retirements. In turn, infrastructure has the potential to promote more durable and equitable growth as the labor market picks up steam following the Great Recession.

Using occupational data from the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, this report provides an update to last year’s analysis measuring the extent and impact of infrastructure jobs. It focuses on national and metropolitan levels of infrastructure employment in 2013, in addition to post-recession employment changes since 2010. The report also explores infrastructure wages in greater depth from 2003 to 2013 to highlight trends in pay, especially for workers at lower ends of the income distribution, i.e., at the 10th and 25th percentile of all wage earners. The report finds that:

1. In 2013, nearly 14.5 million workers—11 percent of the U.S. workforce— were employed in infrastructure jobs, many of which have relatively low barriers to entry.

2. From 2010 to 2013, infrastructure employment jumped 5 percent, exceeding the national average (4.3 percent) across all occupations while expanding opportunities to workers with less formal education.

3. Infrastructure occupations often provide more competitive and equitable wages compared to all jobs nationally, consistently paying up to 30 percent more to low-income workers over the past decade.

Further information on infrastructure job classifications and methods is available in a downloadable appendix.

In 2013, nearly 14.5 million workers—11 percent of the U.S. workforce—were employed in infrastructure jobs, many of which have relatively low barriers to entry.

Nationally, 14.5 million workers are employed in infrastructure jobs, most of which are concentrated in 95 different occupations, ranging from material movers and truck drivers to electricians and water treatment plant operators. In turn, workers in these occupations are engaged in a variety of industrial activities that transport passengers, move goods, produce energy, distribute water, and transmit information, which underscore their sizable economic importance across the public and private sector. For example, more workers are employed in infrastructure than are employed in education (12.7 million), manufacturing (12.0 million), and professional-scientific-technical services (8.0 million).

More than 64 percent of infrastructure employment (9.3 million workers) is concentrated in the 100 largest metro areas. New York, Los Angeles, and Chicago rank among the markets with the most infrastructure jobs, employing a combined 1.9 million workers. By comparison, logistics hubs like Louisville, Ky. and Memphis, Tenn. and energy centers like New Orleans and Baton Rouge, La. have the highest share of these workers, at nearly 15 percent of local employment.

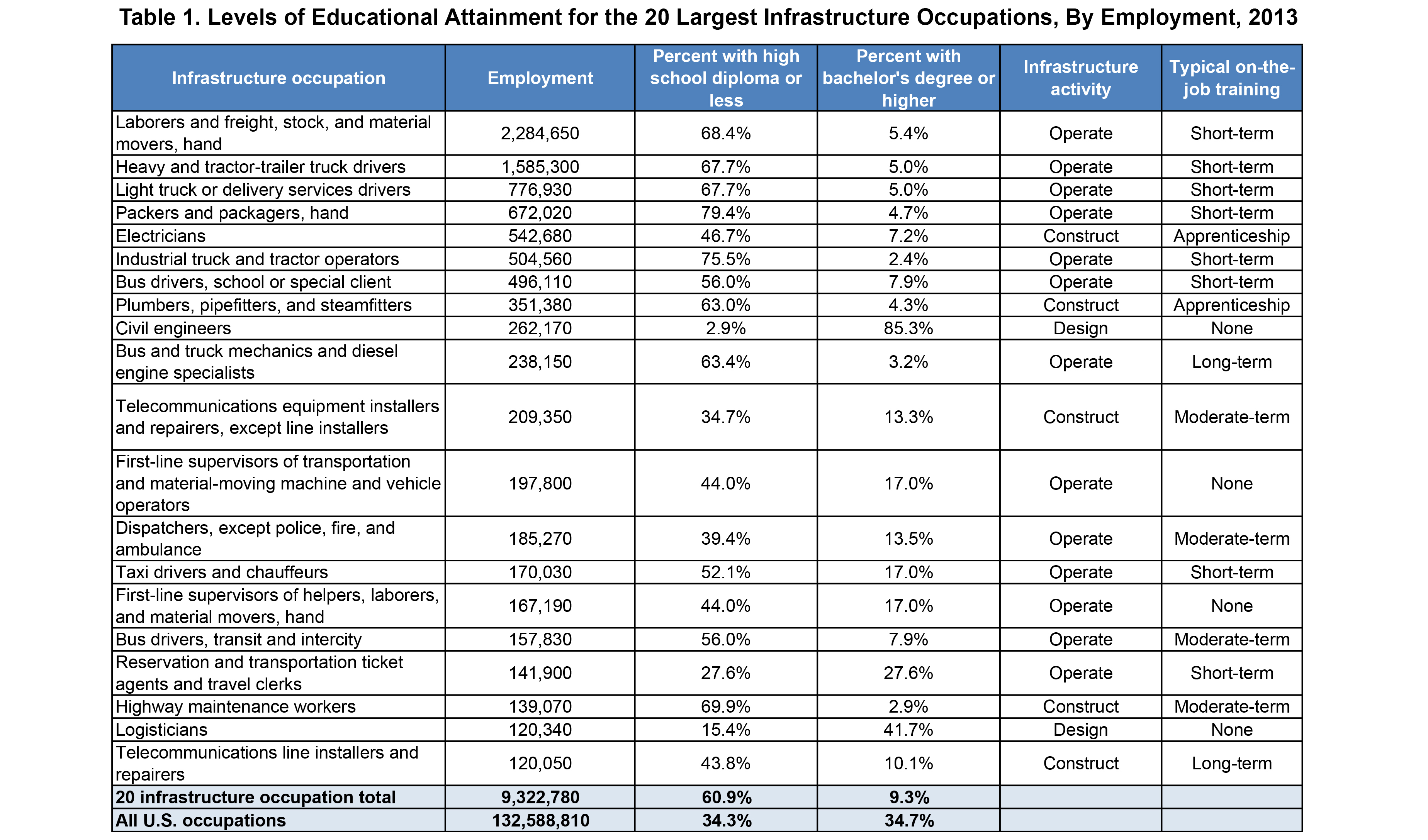

Beyond infrastructure’s enormous economic impact, though, these jobs frequently translate into long-term opportunities for workers across all skill levels. Most workers in the field (78 percent) concentrate on operating infrastructure, rather than constructing (15 percent), designing (6 percent), or governing it (1 percent). Consequently, unlike many other jobs, infrastructure positions often prioritize on-the-job training and have lower educational boundaries to carry out their duties. Only 12 percent of infrastructure workers have a bachelor’s degree or higher compared to 34 percent nationally. Likewise, just 13 of the 95 infrastructure occupations require a bachelor’s degree or higher for entry—such as civil engineers and landscape architects—while 67 occupations are generally filled by workers with a high school diploma or less. These patterns clearly emerge among the 20 largest infrastructure occupations overall.

Source: Brookings analysis of BLS Occupational Employment Statistics and Employment Projections data

From 2010 to 2013, infrastructure employment jumped 5 percent, exceeding the national average across all occupations (4.3 percent) while expanding opportunities to workers with less formal education.

Over the next decade, infrastructure occupations are projected to increase their employment by 9.1 percent and will need to replace almost 2.7 million workers due to retirements and other employment shifts. Some occupations, like solar photovoltaic installers and wind turbine service technicians, are expected to grow quickly. In contrast, plant operators, subway operators, and other related occupations in water utilities and transit agencies are expected to see a growing number of retirements, prompting the recruitment of a new generation of workers.

Since the recession, many infrastructure occupations have already demonstrated a gradual rise in employment. Since 2010, total infrastructure employment grew by approximately 686,330, including 435,450 additional workers concentrated in four occupations alone: material movers, truck drivers, bus drivers, and electricians. As a result, infrastructure jobs focused on operation have tended to lead these gains, coinciding with a rise in freight and passenger traffic. On the other hand, occupations involved in governance, design, and construction—such as conservation technicians, architectural drafters, and pipelayers—have experienced flat growth, likely due in part to constrained public budgets for new capital projects.

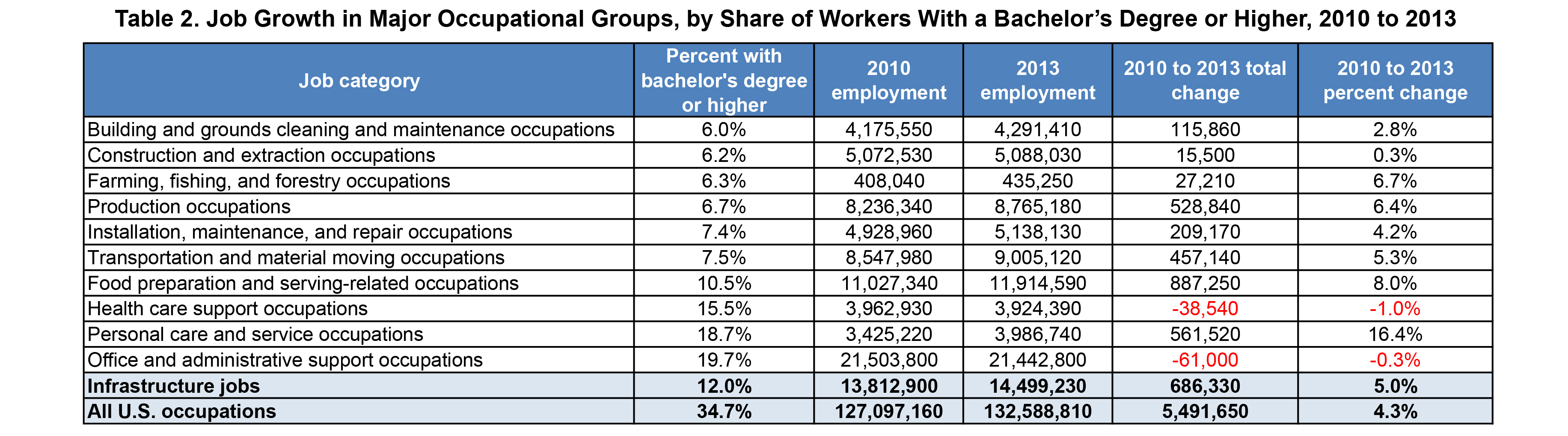

While personal care occupations (16.4 percent) and computer and mathematical occupations (12.6 percent) have experienced the most rapid post-recession expansion, infrastructure jobs stand out in the opportunities they offer workers with less formal education. For example, infrastructure occupations saw faster job growth (5 percent) compared to many non-infrastructure occupations that also appeal to workers with a high school diploma or less, such as those involved in grounds cleaning (2.8 percent) and installation (4.2 percent). Likewise, among occupations employing the smallest share of workers that hold a bachelor’s degree or higher, infrastructure added the second most jobs since 2010, after low-paying food preparation occupations.

Source: Brookings analysis of BLS Occupational Employment Statistics and Employment Projections data

Note: Employment in individual occupational groups may overlap with infrastructure totals, particularly in transportation- and construction-related occupations.

As more infrastructure jobs emerge across the country, metropolitan areas are driving much of the growth. From 2010 to 2013, the 100 largest metro areas added 561,590 of the 686,330 infrastructure jobs, or about 82 percent of the U.S. total. In addition, these areas have seen their infrastructure employment rise by 6.4 percent over this same span, slightly above the national growth rate for these jobs (5.0 percent).

Combined, the 15 metro areas that added the most infrastructure jobs (353,030) over the past four years, led by New York, Houston, and Chicago, accounted for more than half of the country’s total infrastructure growth. Meanwhile, Boise, Idaho, Lakeland, Fla., and Greensboro, N.C.—metros that emphasize trade and logistics—experienced rapid growth, increasing their infrastructure workforce by almost 20 percent. In some places, like Atlanta, Ga. and Fresno, Calif., infrastructure jobs made up more than a quarter of all jobs added since the end of the recession, reflecting widespread hiring in transportation, warehousing, and utilities.

Infrastructure occupations often provide more competitive and equitable wages compared to all jobs nationally, consistently paying up to 30 percent more to low-income workers over the past decade.

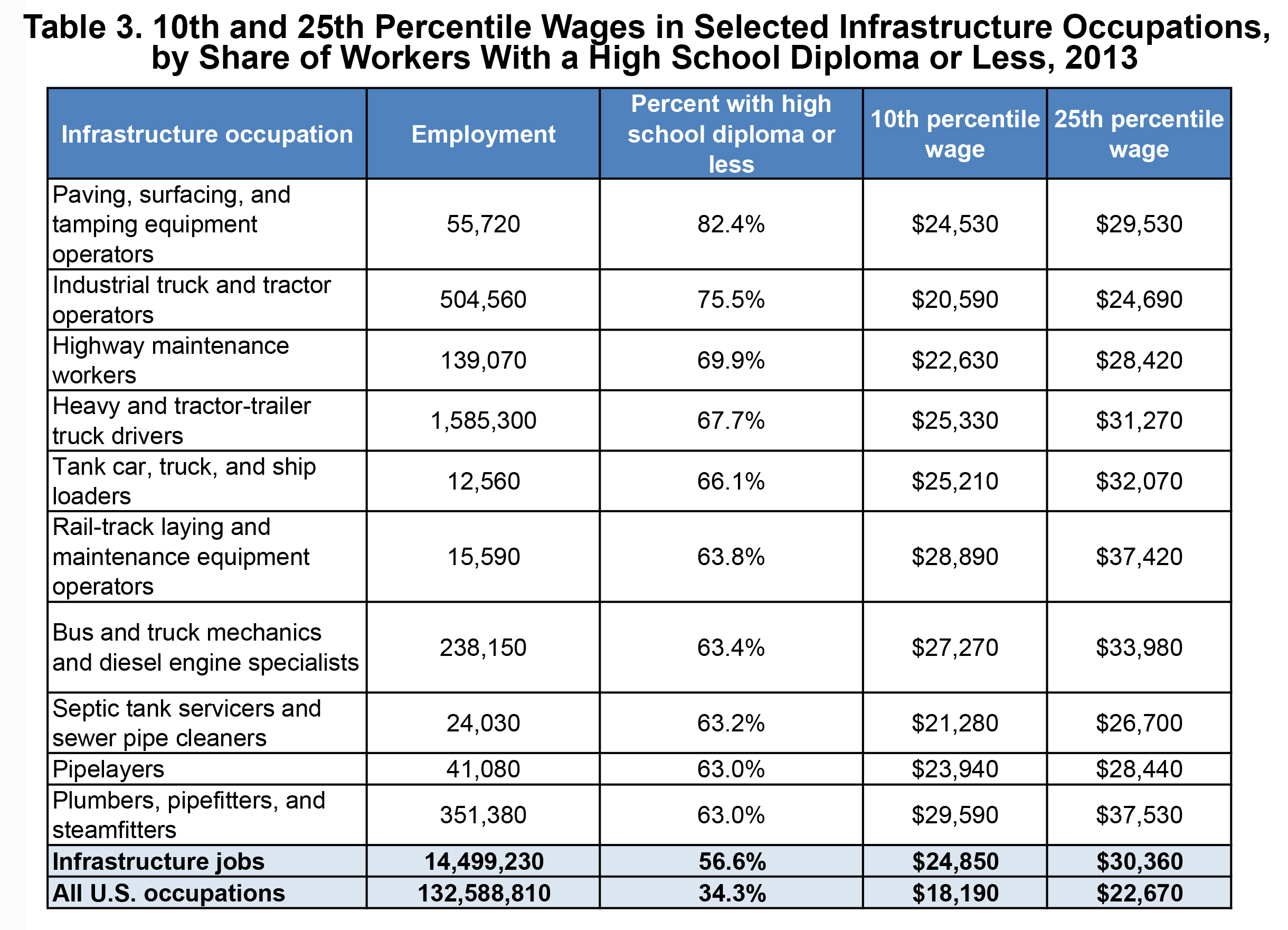

For workers at the 10th and 25th percentiles, infrastructure occupations paid considerably higher wages in 2013 ($24,850 and $30,360 annually) relative to all jobs across the country ($18,190 and $22,670). From plumbers and aircraft mechanics to logisticians and nuclear power operators, wages can vary depending on the specific line of work, but nearly 8 million workers in over 80 of the 95 infrastructure occupations earn higher wages at these percentiles. In addition, median wages for infrastructure workers ($38,810) top the national median ($35,080).

Infrastructure’s importance at these wage levels also extends to workers with less formal education. Unlike numerous service and food preparation occupations—like cooks, dishwashers, and cashiers—that pay the lowest wages nationally, infrastructure jobs offer higher pay to workers at the 10th and 25th percentile and also have relatively low barriers to entry. Industrial truck operators, highway maintenance workers, and bus mechanics rank among the largest infrastructure occupations in this respect; more than 60 percent of these workers have a high school diploma or less.

Source: Brookings analysis of BLS Occupational Employment Statistics and Employment Projections data

From 2003 to 2013, infrastructure occupations continued to offer relatively high wages to workers at these low income levels, even as concerns over inequality mounted during and after the recession. For example, despite general wage stagnation across all occupations—including nearly a 5 percent fall in real wages for workers at the 10th and 25th percentiles over this 10-year period—infrastructure occupations maintained their advantage for lower-income workers.

When adjusted for inflation, this advantage in pay actually increased 12 percent between 2003 and 2013, with infrastructure jobs offering almost $6,700 and $7,700 more annually to workers at the 10th and 25th percentiles, respectively, compared to all jobs nationally at the end of the period. High levels of unionization among public-sector employees, along with other industry norms, have likely contributed to these competitive wage practices.

Although infrastructure occupations still pay slightly less on average than all jobs ($41,350 versus $46,440)—and much less at the 75th and 90th percentiles—they continue to promote a more equitable distribution of incomes over time. For instance, the ratio of wages earned by infrastructure workers at the 90th and 10th percentiles have remained considerably low—2.5—compared to all workers nationally (4.9). From septic tank servicers (2.6) to rail yard engineers (2.1), this equitable wage distribution across all types of infrastructure occupations stands in stark contrast to larger national-level trends, where the gulf between workers at the 10th and 90th percentile has increased from 4.5 to 4.9 since 2003.

Conclusion

Infrastructure’s sizable and enduring impact on the labor market underscores the need for public and private leaders to continue prioritizing physical investments that propel economic growth. Stimulus spending and other stopgap measures fail to provide the kind of certainty that regions and millions of workers need when constructing, operating, governing, and designing major infrastructure assets.

The equitable nature of these jobs, particularly when it comes to pay, also speaks to the importance of recruiting and training more infrastructure workers during the ongoing recovery. As infrastructure occupations experience growth or face shortfalls in hiring and retention, they can expand opportunity for years to come.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).