Scientists and activists put the problem of global warming on the national agenda in the late 1980s. Since then, five different presidents have occupied the White House, leading to five disparate federal strategies for managing the emissions that cause climate change.

Whipsawed by Washington, activists and policymakers have instead turned inside the country, notably to cities. Since 1991, over 600 local governments in the United States have developed climate action plans that include greenhouse gas inventories and reduction targets, reflecting growing public concern about the consequences of a warmer planet. Recently, this local action has been accelerating. But despite numerous studies, we still don’t know if all this effort is working.

Now, a team of scholars organized by the Brookings Institution has built and analyzed one of the most comprehensive statistical evaluations of just what’s happening in a cross section of diverse cities on emissions reductions. Unlike earlier studies—which tend to focus only on the places that have made climate pledges—we looked at all of the nation’s 100 largest cities to get a dose of realism about how much of the country is really engaged in confronting climate change.

From that perspective, what cities are doing is—at best—a start. As of 2017, only 45 of the 100 largest cities had any serious climate pledge at all, and many of those pledges are more aspirational than realistic. About two-thirds of cities with climate pledges are currently lagging in their targeted emissions cuts, while 13 others don’t appear to have available emissions tracking in place.

Still, the places that have made climate pledges are making a modest dent in emissions. The 45 cities with pledges will, by themselves, eliminate about 6% of total annual U.S. emissions compared with 2017 levels, which adds up to the equivalent of 365 million metric tons of carbon pollution—a volume equal to removing about 79 million passenger vehicles from the road. This kind of concrete action is what Brookings President John R. Allen calls “American leadership”: action embedded within the country, even when Washington seems impotent.

Of course, cities acting on their own can’t stop climate change; that requires global cuts in carbon pollution to nearly zero. Instead, cities’ efforts matter because they—to extend former Supreme Court Justice Louis Brandeis’s dictum into the era of deep decarbonization—are laboratories of action. Some of the hardest tasks in cutting emissions involve activities such as urban planning and rebuilding transportation infrastructures, where cities are on the front lines.

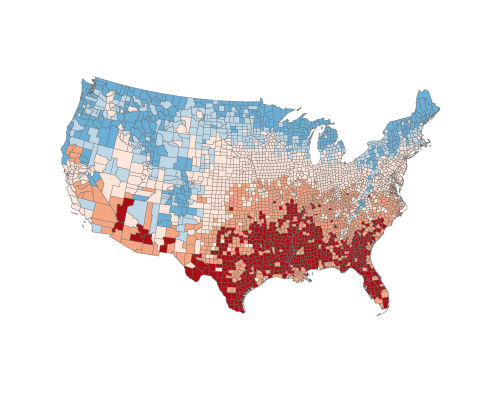

Already, leading cities are having an impact, as shown in the figure above. And these big reductions are a signal of what’s to come. Some of the patterns are what you’d expect: Half of the top six cities for emissions reductions are in California. Other top performers include cities in the Democratic-leaning arc that swings up the West Coast of the United States, across much of the North, and down half of the Eastern Seaboard. But even more interesting are the “purple” areas that are shifting politically, and where topics such as climate change are centrist: Greensboro and Durham, N.C., Cincinnati, Ohio, Richmond, Va., and many others. Geographically, local climate pledges are relatively evenly distributed—a good sign that action on climate change is spreading throughout the urban heartland.

Looking to the future, the cities that are pledging to make the biggest cuts in pollution volumes are, not surprisingly, the largest and greenest. They have big pollution loads today (thanks to their size) and powerful commitments to act. For leaders there, vigilance is needed to make sure pledges become reality, as some of the places pledging big cuts are already struggling to make a dent—Philadelphia and Phoenix, for example.

Some of the largest achievements, meanwhile, have emanated from the electric power sector. For cities such as Los Angeles, the closure of coal plants (that sent their power to the city long distances via wire) have offered big reductions. But every city planner knows that the real frontier where their actions are most pivotal is in managing sprawl and transportation.

These factors have two huge implications for national and foreign policy on climate change.

First, the cities-as-laboratories theory of change has a lot to offer, especially when Washington is flaky, gridlocked, or both. But it only works if the efforts don’t stop with the pioneers. After all, more than half of the nation’s largest cities lack serious climate plans, and many of the plans that do exist lack viable agendas for implementation. Highly qualified city planning offices—as in San Diego, for example—are not universal. This matters because the theory of change at work here—one that starts with decentralized actions and experiments—requires diligent review and assessment to learn what really works. Very little of that evaluation is occurring, and there is a danger that all this decentralized action could lead to chaos and drift. Pioneers are important, but “followership” in medium-sized cities and the Midwest is going to be equally essential.

Second, with each change in leadership at the White House, the pendulum of federal policy has swung wider and harder. The imminent election may swing it again, and if it does, the U.S. will once again proclaim “we’re back” for international diplomacy on climate change. But that diplomacy won’t matter much if the rest of the world doesn’t believe our promises will stick and doesn’t see climate action in areas that have resisted thus far. The solution to this problem isn’t more diplomacy, but more mayors making (and delivering on) compelling emission reductions pledges.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).

Commentary

Cities are pledging to confront climate change, but are their actions working?

October 22, 2020