This week the World Health Organization (WHO) issued a new set of guidelines on “Physical Activity, Sedentary Behaviour and Sleep for Children Under 5 Years of Age.” But to read the mainstream media coverage, you would think it was all about “screen time.”

“WHO Says Limited or No Screen Time for Children Under 5,” announced the New York Times headline. Time magazine went with “World Health Organization Issues First-Ever Screen Time Guidelines for Young Kids.” While neither of these headlines are inaccurate, they are misleading. WHO was actually addressing physical inactivity in early childhood—“a leading risk factor and a contributor to the rise in overweight and obesity.” Screen time wasn’t the primary focus.

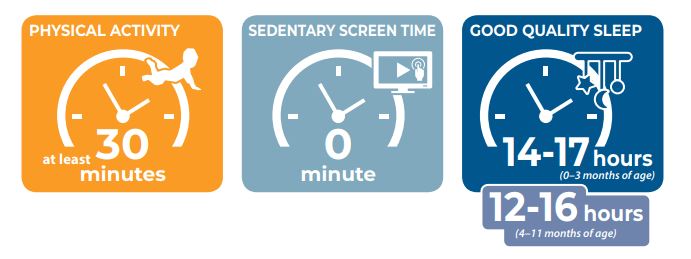

But don’t blame the media for the mischaracterization. It’s WHO itself that chose to give an oddly disproportionate amount of attention to “sedentary screen time,” a category the organization defines as: “Time spent passively watching screen-based entertainment.” Throughout the new guidelines, WHO presents “sedentary screen time” as one of three main categories, along with “physical activity” and “good quality” sleep. These are represented with large colorful graphics as shown below, implying that screen time limits are equally as important to early childhood wellbeing as sleep and exercise. Of course, that’s not true, not even by the guidelines’ standards.

“There was moderate to very low-quality evidence for screen time and adiposity, motor and cognitive development and psychosocial health,” the document states, confirming what most researchers already know: There’s only very weak correlative evidence linking screen time to negative outcomes.

Unsurprisingly, many prominent researchers took umbrage with the attention given to screen time, arguing that WHO’s screen time recommendations are based on bad science. “There is currently no clear evidence for the specific duration limits proposed at this age range,” said Dr. Tim Smith at the Centre for Brain and Cognitive Development in Birkbeck, London.

Similarly, Andrew Przybylski, the Director of Research at the Oxford Internet Institute, University of Oxford, said: “The authors are overly optimistic when they conclude screen time and physical activity can be swapped on a 1:1 basis.” He added that, “the advice overly focuses on quantity of screen time and fails to consider the content and context of use. Both the American Academy of Pediatricians and the Royal College of Paediatrics and Child Health now emphasize that not all screen time is created equal.”

Without a doubt, we should encourage young children to get plenty of physical activity and to adopt healthy sleeping routines. Likewise, caretakers probably shouldn’t let kids sit in front of a screen all day. But by focusing on screen “exposure”—and perpetuating the unsubstantiated myth that screens can be toxic—WHO is reinforcing a problematic attitude toward digital technology that could potentially cause even more harm in the long run.

As I explain in my book “The New Childhood: Raising Kids to Thrive in a Connected World,” many of our concerns around kids and technology—video games, digital devices, social media—are really about nostalgia and an unconscious fear of change. We don’t want to disrupt our most familiar conception of the childhood experience. But we need to remember that most of the things we consider to be the purest forms of child’s play, like the playground and the sandbox, were established during the Industrial Age. They lead to positive, healthy outcomes, not because they are essentially “good,” but rather because they address the unique psychological, social, and emotional challenges of a specific technological and economic context.

In the current context, there are new challenges around healthy child development. Increasingly sedentary lifestyles seem to be among them. Therefore, in the same way that formal physical exercise and repetitive aerobics had to be invented for a post-agrarian world, we will need to find ways to address the fitness needs of a digitally connected world. This is clearly an urgent problem. But while we’re working on solving it, it’s naive and misguided to scapegoat the screens. Instead, we will need to figure out how to integrate technology into the childhood experience in developmentally beneficial ways.

The answer is not more limits and restrictions; it’s more mentorship and guidance. When we treat screens as a forbidden fruit, we reinforce the idea that digital play is an unhealthy temptation that kids enjoy alone, mischievously, and with a bit of guilt and shame. That’s a problem because children need help learning how to engage in positive online behaviors, how to manifest the values we care most about through digital modes of communication, and how to be good citizens of a connected world.

And when it comes to social and emotional well-being, there’s plenty of research pointing toward the benefits of joint media engagement, where grown-ups and children engage in digital play together. I’m not sure why WHO chose to ignore it. What grown-ups really need (and want) is not more fearmongering and parent shaming, but rather, evidence-based guidelines to help them distinguish healthy screen-based activities.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).

Commentary

Children need digital mentorship, not WHO’s restrictions on screen time

April 26, 2019