Schools across the country face teacher shortages in a range of areas, including Career and Technical Education (CTE), which prepares students for postsecondary education and careers. National data shows that administrators report having difficulty filling positions in CTE subjects 57% of the time, compared to only 39% for openings in academic subjects. These reports of difficulty retaining CTE teachers are similar to how administrators report shortages in other hard-to-staff positions like special education. Shortages are particularly pressing in high-demand, high-wage subjects in which teachers may face higher opportunity costs to teach. A report from the National Association of State Directors of CTE describes teacher shortages in manufacturing (81% of surveyed state CTE directors reported shortages), IT (73%), health sciences (71%), and STEM CTE.

Teacher shortages in areas with parallel strong demand in the private sector are not surprising. For example, we might expect that teachers with training and work experience in high-growth areas such as STEM, health sciences, and IT would be more likely to leave teaching for higher wages and be more difficult to replace. If true, then these shortages may contribute to a vicious cycle between labor supply and demand in the field. Namely, too few workers in high-demand occupations makes it easy for employers to poach teachers in those areas, but losing teachers makes it harder to build the next generation of workers in those industries. In high schools this is further a problem because evidence suggests that CTE course-taking can improve student’s chances for high school graduation as well as higher earnings and later employment, particularly among low-income students. Without CTE teachers in these fields, high-quality courses and programs cannot be offered, impacting students’ prospects in the near term, and potentially hindering economic growth later.

Insights on CTE workforce dynamics from Tennessee

In a recent study, we examined CTE teacher turnover in Tennessee and the mechanisms that may explain differences in turnover by subject area, as well as the policy implications in the specific case of health science teachers. As in many states, CTE teachers in Tennessee can enter the teaching profession through two different pathways: either by pursuing a traditional teacher certification program via a bachelors’ degree (more typical for business or agriculture teachers) or through occupational pathways that prioritize professional experience in related occupations and with more flexible education requirements (more typical for construction trades, cosmetology, IT, and health services).

CTE teachers make up 18% of high school teachers in the state, and the composition has been changing over time to reflect economic need. In the study, we examined CTE turnover along two dimensions—license type and content area taught. We consider CTE teachers in high-growth areas (IT, health sciences, and STEM) in comparison to other groups of teachers. We construct this high-growth category because these programs align with rapidly growing industries in the state (and nation). The number of teachers in these high-growth areas have grown over time in the state, with relative declines in trades and business, as well as other professionally certified CTE areas such as human services, hospitality, and education.

To conduct the analysis, we used administrative data from Tennessee on teachers, courses, and students, to trace teacher turnover and the impact of this turnover by subject area. One of our novel contributions is our ability to track those who leave teaching into non-teaching employment among those who remain employed and in the state.

We found that teachers in the high-growth, hard-to-staff CTE areas are: 1) more likely to leave teaching; 2) difficult to replace, creating net reductions in the number of students who can be served; and 3) earn the most money in their post-teaching employment compared to other high school teachers who exit teaching. We describe each of these points in further detail below, and collectively they highlight the need for policy response.

Occupationally licensed CTE teachers more likely to leave

We first examined teacher turnover by license type. CTE teachers who hold professional teaching licenses are slightly less likely to leave teaching than their non-CTE peers (who similarly hold professional teaching licenses), whereas occupationally licensed CTE teachers have a more than 25% higher rate of exit than non-CTE teachers. Though we might like to compare whether teachers in the same CTE fields leave at different rates based on their license type, this is not really possible in our context. In fact, the different paths to licensure are meant to address the fact that traditional teacher preparation programs do not exist in some CTE areas (e.g., cosmetology), and the time and financial costs of entry via traditional teacher licensure are precisely the reason that occupational routes are the de facto sole pathway into teaching in these CTE areas.

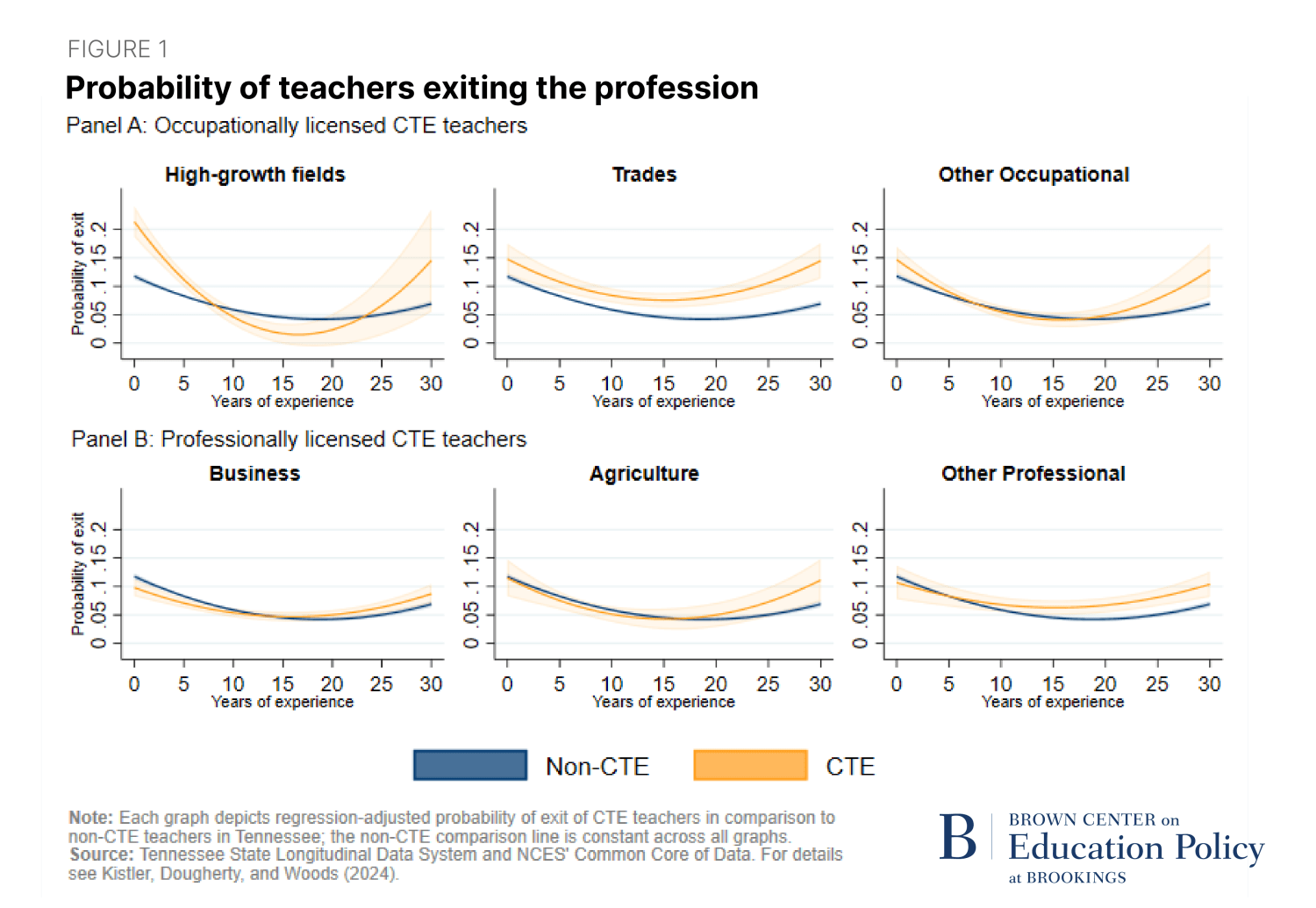

We also looked at differences in the CTE certification fields and found teachers in high-growth fields are also more likely to leave teaching early in their teaching careers. In Figure 1, we present fitted probabilities of exiting teaching by years of experience, accounting for important differences among teachers such as gender, race, and school context. Each panel of this figure estimates the likelihood of turnover for all non-CTE teachers compared against a specific set of CTE teachers (that is, the curve for non-CTE teachers is the same across graphs). The top three panels correspond to our three groups for occupationally licensed CTE teachers, and the bottom three correspond to the groups of professionally licensed CTE teachers. All figures show a U-shaped exit probability among teachers, which is a widely documented pattern in prior research. But the most salient feature here is the substantially higher rate of exit among high-growth, occupationally licensed CTE teachers with fewer than 10 years of experience and the generally higher rate of exit among trade teachers with all years of experience. Also, the bottom row shows the similarity of attrition patterns between professionally licensed CTE teachers and their non-CTE counterparts.

CTE teachers most likely to turnover also earn more

We also found those who leave teaching at the highest rate are also those who earn more in non-teaching employment. On average, non-CTE teachers who exit earn just over $90,000 total in the two years after exiting, with other professionally licensed CTE teachers who leave earning similar amounts. In contrast, occupationally licensed CTE teachers earn considerably more than professionally licensed teachers after exiting. Those in high-growth areas earn nearly $110,000 (about 20% more) in these two years after leaving teaching. Former trades teachers also show a substantial earnings premium.

Taken together, these results suggest that occupationally licensed teachers likely face more favorable non-teaching options, at least in terms of pay, than those in lower-demand areas or with professional licenses. This difference is likely explained by the fact that occupational teaching licenses are designed to create a pathway into the classroom for industry professionals who potentially have stronger ties to the private market and face greater opportunity costs to teach. In turn, those higher wages in the private industry may be a powerful pull out of teaching.

Our results stand in contrast to other recent work from Washington state showing that teachers earn less outside of teaching, though we can reconcile these different findings. Not only is average teacher pay significantly higher in Washington than in Tennessee, but that study also aggregates all elementary and secondary teachers together, ignoring differences across specializations. On the other hand, we find large differences in pay by field after leaving teaching—even among CTE teachers in different fields—which highlights the fact that CTE teachers in high-growth fields face starkly different alternative work opportunities than other teachers.

Teacher exit creates course shortages in high-growth areas

By focusing in on health science as a particularly important case, we find that when health science teachers leave their school, they are not always successfully replaced, which results in a net loss of course section offerings. We find that for each health science teacher who leaves, there is a net loss of about one-half of a teacher, on average, in the next year. The fact that losing a teacher does not result in the loss of a full teacher in the next year suggests that some schools successfully rehire (though in about half of cases, they do not).

If exited teachers cannot be perfectly replaced, schools could potentially respond to reductions in the number of health science teachers by increasing class sizes or reducing the number of course sections offered. We estimate that the loss of a health science teacher results in a net loss of roughly one section of related coursework. And, among schools that continue to offer health science courses, we demonstrate that health science teacher turnover does not result in larger classes. These findings imply that turnover among health science CTE teachers results in a net reduction in the number of students participating in health science coursework.

Policy ideas to counter CTE teacher attrition

In summary, we find that CTE teachers with occupational licenses and in high-growth areas are much more likely to leave the profession, earn nearly 20% more in private industry, and their departure from the classroom sometimes results in fewer learning opportunities for students. These results suggest a few implications for both policy and practice.

First, to address shortages, policymakers need to consider how to further lower the barriers to entry. Though the occupational pathway already removes some requirements for licensure, creative policy solutions may help to increase the number of industry professionals who become teachers. For example, offering opportunities for industry professionals to work as teachers in schools part-time may help to address urgent shortages and provide a pathway into teaching. It might also allow some teachers to more easily straddle both the teaching and non-teaching workforces, perhaps diminishing the compulsion to leave teaching altogether as well as helping them to keep their skills sharp and maintain employment networks for their students.

Second, policymakers and school leaders should consider strategies to support and better retain CTE teachers with occupational licenses who are new to teaching. These teachers in skilled trades, health services, and IT, by definition, have less educator preparation for the job of teaching and may need more support in their transition. Given their stronger alternative job opportunities, school leaders and policymakers should strive to improve working conditions and increase pay to make teaching more attractive.

The provision of CTE coursework in high schools, especially in high-growth fields, promotes student engagement, high school completion, and later employment, especially among disadvantaged student groups. But the provision of quality CTE courses depends on an especially transient segment of the teacher workforce, consisting of people moving between teaching and industry. On net, this mobility may not be something we can fully remove, but smart policies could help stabilize the workforce and learning opportunities for students.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).