The Global Economy and Development program is pleased to welcome Eduardo Levy Yeyati back to the Brookings Institution as a senior fellow. Eduardo was previously a nonresident senior fellow with Brookings and has published extensively with us on issues from debt and monetary policy to labor markets and income inequality.

This week, Esther Lee Rosen, senior director of communications at Global, sat down with Eduardo to discuss his research agenda and the future of work in the age of artificial intelligence.

Esther Lee Rosen (ELR): Welcome to the Global Economy and Development team at Brookings! We are thrilled to have you join us.

Eduardo Levy Yeyati (ELY): I am delighted to be here, working with such a talented group at these challenging times.

ELR: You are now leading Global’s Workforce of the Future initiative, which has focused on issues such as effective economic development planning and the importance of immigrants to the American workforce. What are key issues you will focus on in the coming months?

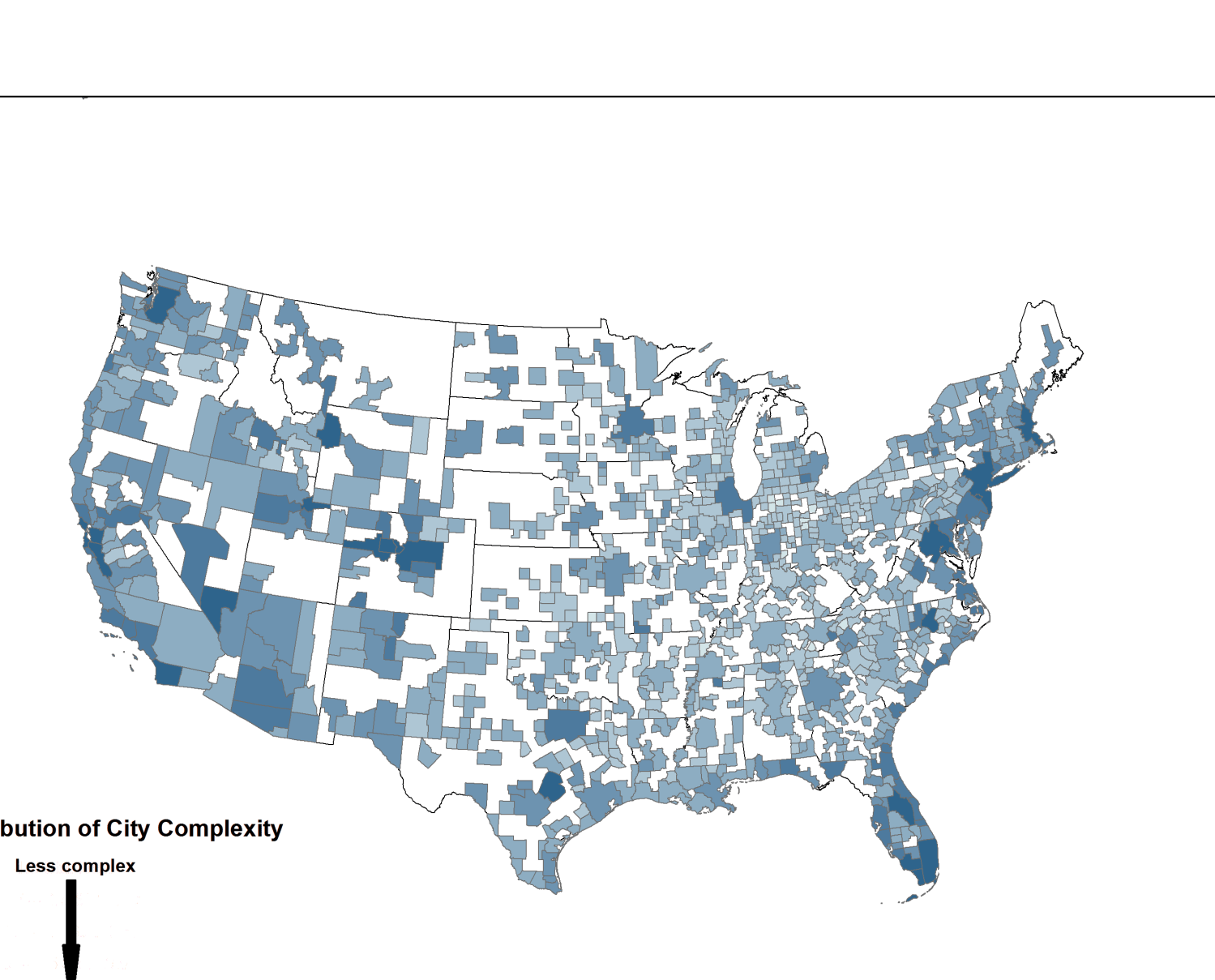

ELY: The initiative, with which I collaborated in the past, has so far successfully focused on local development, reskilling, and the inclusion of immigrants in the U.S., as well as building data-intensive tools for policymakers that are currently being used to guide productive and training strategies in several U.S. states. But we all know how the world is mutating due to demographic, geopolitical, and most notably, technological changes, all of which call for a significant updating and extension of these tools.

Take, for example, the implications of generative artificial intelligence (AI) for the labor market, particularly the need to orient training toward skills that complement rather than compete with AI. This should reshape the way we think about the connection between education and training with jobs, which would in turn call for the redesign of our tools. It also brings huge opportunities. I am convinced AI can significantly help us improve the way we use our data and calibrate our models.

Moreover, the Workforce of the Future initiative’s research, which aims at helping men and women in precarious low-productivity, low-wage occupations to find a path to good jobs, should be particularly useful to reduce labor segmentation and inequalities in developing countries in Africa or Latin America where low-skilled, informal workers represent an important share of the labor force. Adapting and extending our tools for the context of these countries should be one of our priorities. Again, AI may have a positive impact as it could benefit relatively unskilled workers—as a recent study shows—helping developing countries to leapfrog on labor productivity.

The same is true for learning and employment records, a truly valuable vehicle to reduce information asymmetries in the labor market, which can be substantially enhanced by AI, and may prove especially impactful in dual labor markets in the developing world.

ELR: What are the longer-term research agenda and focus you are interested in pursuing?

ELY: The intersection of a human-centered AI and the future of work is a fascinating and growing area for policy research, which I have been working on and writing about for the past few years. Frankly, this area is moving so fast that sometimes I cannot keep up with the pace: The upcoming revised edition of my last book on AI and the labor market will probably be almost a completely new book rather than a simple update.

The field is vast. The issues I cover range from the economics of AI and its impact on labor and distribution, to incipient AI regulation and its influence on tax and education reform, with the broader goal of increasing preparedness to profit from technological change while avoiding labor market disruptions or the Turing trap: the temptation to use inferior technologies to reduce costs with no gains in productivity.

An important and sometimes overlooked aspect of this intersection is the fact that AI, by construction, captures and uses very effectively knowledge that is documented in data, such as numbers, images, and language, while failing to emulate experiential and practical knowledge, which is sometimes as important if not more, as I argued in a recent blog. This paves the way for a fruitful complementarity, if only we adapt our education to focus more on these learning areas.

I cannot emphasize enough the importance of this issue. Labor income is the key distribution channel: Until we find another sustainable way to distribute income, we need to preserve it.

ELR: How is technology like AI impacting the labor force? What are some opportunities AI provides—and what are its potential risks?

ELY: To answer that, bear in mind that technology is still in its exponential phase—in other words, we still don’t know where it will be once it matures. For example, the World Bank in 2016 predicted that developing countries were the most exposed to substitution, whereas a similar study by the IMF in 2024 concluded the opposite. Why? Because we used to think that middle-skilled jobs were first in line, but generative AI is now competing with more sophisticated tasks. Indeed, AI creates a “Robin Hood effect” whereby the most qualified lose against the less qualified, a mixed blessing since this is likely to reduce labor income inequality but also the labor share in output.

That said, I already mentioned that generative AI is more complementary than usually thought: To the extent that we adapt to profit from this complementarity, there may be fewer jobs in the future, but they will be better jobs, more productive and lucrative.

But we must be cautious. The incipient adoption of AI that we see is barely a preview of things to come once the technology stabilizes and firms approach it not as an accessory but as the foundation of a new way to organize production, which will take longer than technologists predict.

Ultimately, though, we need to prepare. There will be fewer jobs, meaning a decline in demand for paid hours, labor shares will likely continue to drift downward, and the jobs that remain, perhaps with the same names, will have a different task composition. I don’t want to sound repetitive, but we need to reevaluate the way we think of education and training, and we need to promote human-centered technologies.

On the positive side, the fact that AI does not substitute for experience and judgment may tilt education and jobs toward the aspects of work that are more intrinsically human, if we prepare accordingly, that is. More reason to continue with the work of the Workforce of the Future initiative and on the learning and employment records agenda, which I am convinced will be essential for a smooth transition to a better future.

ELR: In your experience, what are some key challenges to labor inclusion and further, how do we prepare the labor force for the present and future?

ELY: The challenges depend on the countries. In the developed world, concerns are often associated with the future: the fear that technology may substitute jobs or depress wages; the winner-takes-all nature of many new activities, which may lead to concentrated markets and lower wages; or the rapid change in the competences demanded by the market, which results in a mismatch with workers’ current skills that may foster unemployment or overqualification.

In developing economies, to the previous list we add pending assignments from the past: informality, low human capital, and an education system often indifferent to labor inclusion. In other words, policymakers need to bridge the gap between insiders and outsiders while aiming at the moving target of future labor demands, all of which makes active labor market policies tremendously complex.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).

Commentary

Opening paths to good jobs—Welcoming Eduardo Levy Yeyati back to Brookings

November 21, 2024