Content from the Brookings-Tsinghua Public Policy Center is now archived. Since October 1, 2020, Brookings has maintained a limited partnership with Tsinghua University School of Public Policy and Management that is intended to facilitate jointly organized dialogues, meetings, and/or events.

President Trump’s speech at the APEC CEO Summit in Danang, Vietnam took a strategic approach and offered few details beyond restating Trump’s preference for bilateral trade deals over multilateral accords. This idea so far appears to have fallen flat, write Jonathan Stromseth and Ryan Hass. This piece originally appeared in Nikkei Asian Review.

U.S. President Donald Trump’s call for countries to work together to promote a peaceful, prosperous and free Indo-Pacific region in his speech at the APEC CEO Summit in Danang, Vietnam will be generally welcomed given its largely unobjectionable nature.

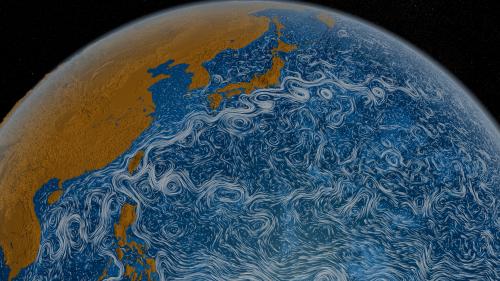

His administration sees the geopolitical center of gravity shifting to the Indo-Pacific, a geographic expanse spanning the entire Indian Ocean, the western Pacific and the countries that surround the two bodies of water, with the key players being the democratic nations of India, Japan, Australia, and the United States.

The speech was highly anticipated, particularly following Trump’s withdrawal from the Trans-Pacific Partnership, his tight focus on North Korea, the seeming absence of an affirmative American agenda for the region, and China’s concurrent efforts to place itself at the center of virtually every major regional initiative. Many Asian leaders and experts, especially those from the 10 countries that make up the Association of Southeast Asian Nations, were eager to see if Trump would offer fresh and actionable ideas for further integrating the region and spurring economic development—in other words, whether Trump would commit to linking American power to the aspirations of the region’s people.

The speech took a strategic approach and offered few details beyond restating Trump’s preference for bilateral trade deals over multilateral accords. This idea so far appears to have fallen flat. No Asian leader has taken up Trump’s invitation to negotiate a bilateral trade agreement. Meanwhile, the 11 remaining members of the TPP announced an in-principle agreement in Danang to implement the deal without the United States, feeding the perception that the region is moving forward on its own.

Mixed messages

To prevent such perceptions from taking root and doing lasting damage to U.S. standing, it will be important for Trump and his advisers to flesh out what specific results the broader Indo-Pacific strategy is meant to achieve or avoid; what is expected of participants; and whether all countries in the region, including China, can participate or whether the purpose is to limit the expansion of Beijing’s influence. If the underlying motivation is to collectively curb China’s ambitions, the Trump administration will need to develop its arguments as to why other countries should feel confident in partnering with the United States in such an effort.

After heaping praise on Chinese President Xi Jinping in Beijing just 24 hours earlier, Trump still spoke positively about Xi in his Danang speech on November 10. At the same time, however, Trump offered thinly veiled criticisms of China by referring to the predatory industrial policies of “other countries,” noting as well that the United States is seeking friendship and does not dream of domination.

The variance in tone between sweet talk toward Xi in Beijing and tough talk about China in Danang will call into question whether Trump is convinced about his strategy, and whether he will give support to countries that choose to partner with him, even when doing so creates friction in his relationship with Xi.

Almost no Asian country wants to lean too far toward one power or the other and would prefer instead to preserve good relations with both the United States and China.

Even with concerns over the implications of China’s growing regional influence, almost no Asian country wants to lean too far toward one power or the other and would prefer instead to preserve good relations with both the United States and China. The reason is simple: Countries want to enjoy the economic benefits that positive relations with China offer and the security protection offered by the U.S. No country in Asia wants to be forced to choose between China, their permanent and powerful neighbor, and the U.S., their distant and inwardly focused friend.

One way the administration could square this circle would be to focus its Indo-Pacific strategy on strengthening regional institutions and supporting the emergence of issue-based country networks. There does not need to be any single path for promoting freedom, openness and respect for rules in the region. The denser the web of relationships in Asia, the less space there will be for any one country to throw its weight around.

Common challenges

In this sense, the best China policy is a robust and comprehensive Asia policy. The goal of such efforts would not be to limit China’s role in the region, but rather to build multilateral platforms that set common expectations for all members while also lowering the threshold for collective action in addressing common challenges. The more such as initiative is framed around what it seeks to advance rather than what it opposes, the easier it will be to attract support within the region.

Disaster management and response, particularly in Southeast Asia given its high vulnerability to natural disasters, is one potential focus area. The U.S. should lead efforts to create a better resourced and more agile regional disaster response program and welcome China’s contributions.

A related issue is climate change. The U.S., China and other regional countries could take the lead in establishing a climate change trust fund at the World Bank or another institution. Although the Trump administration has backed away from global climate commitments, such a regional initiative would encourage cost-sharing to address the unavoidable effects of shifting weather patterns resulting from changes in sea temperatures. U.S. leadership would not be diminished by China’s contributions. The only thing that would go down would be the potential bill for U.S. taxpayers.

The U.S. should continue to strengthen and modernize its alliances in the region, while developing comprehensive and strategic partnerships with emerging partners such as Indonesia, Vietnam and India. To be effective, of course, the U.S. needs to be engaged not just in the political and security spheres, but also in the economic realm.

Without an affirmative economic agenda for the region that takes into account the integrated nature of Asian supply chains, Washington will lose influence in Asia, no matter how many U.S. aircraft carriers operate in the region. Having exited TPP, the U.S. could be left further behind as talks on other multilateral trade agreements gain momentum, including the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership backed by China.

Trump has delivered the opening chapter of U.S. efforts to advance a comprehensive strategy for the Indo-Pacific. Many countries in the region stand ready to support an affirmative agenda for strengthening the region’s capacity to tackle common challenges. There are practical areas where the U.S. can convene and lead such efforts. It should do so.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).

Commentary

America’s Asia policy must offer a positive agenda

November 13, 2017