In December last year, I argued that “America First” cannot be achieved by “America alone,” but rather, on the back of a strong foundation of allies, partners, and friends, including in Asia. In May this year, National Security Adviser H.R. McMaster and Director of the National Economic Council Gary Cohn appeared to agree. They confirmed that “America First does not mean America alone” and that strong alliances and economically thriving partners are a “vital” American interest.

What Asia wants

Throughout President Donald Trump’s first visit to Asia, the region will be looking for him to demonstrate personal commitment to allies and partners and for an indication of how he intends to work together to advance mutual interests. It worries about alliances and partnerships coming undone at whim and fancy. A clear statement of U.S. interests and priorities in the region will help allay fears.

Critically, the region will be seeking signs that Trump can be trusted to manage relations with China and North Korea. A trade war with China could cripple the region; a nuclear war might well annihilate it. Even short of outright war, failing to properly manage the situation on the Korean Peninsula could set in motion a series of destabilizing events—already there are renewed calls for Japan and South Korea to become nuclear-armed states. Some argue that this would mean greater stability in the longer run, but we should not too readily assume rational actors into the future, even if that assumption were true today. Many countries in Asia will also be looking for indications that the president’s understanding of U.S. interests is not a narrow one, but includes appreciation of the critical role the region’s multilateral institutions and international law play in maintaining peace, stability, and prosperity for all.

The United States’ ability to enunciate and pursue a coherent Asia strategy balancing firmness in defense of international law and norms, on the one hand, and prudence, on the other, will have an important impact on how the region views its leadership role. “Whack-a-mole,” or a reactive approach to lashing out at actors who have displeased the U.S. president, should not substitute for strategy in the region.

A trade war with China could cripple the region; a nuclear war might well annihilate it.

Less than promising start

Early indicators that Trump will satisfy some or all of the region’s wish list are less than promising. On October 24, the White House said that Trump will be skipping the East Asia Summit taking place in the Philippines at the end of his trip. The summit is recognized by Trump’s own state department officials as the “premier forum for security discussions in the Asia Pacific.” Last Friday, however, Trump turned around and decided that he would, after all, attend “the most important day” of the summit.

Bowing out of the summit would have been a missed opportunity for the United States to demonstrate commitment to key institutional frameworks. It would also have allowed fellow member states like China and Russia greater leeway in shaping the rapidly changing strategic landscape. It is thus a good thing that Trump eventually decided to attend. However, his initial “no” suggests he lacks a clear understanding of what is at stake. His flip-flopping entrenches perceptions of an erratic leader.

Trump’s withdrawal of the United States from the Trans Pacific Partnership has already denied the country of a potent tool of regional influence. The trade deal was the economic pillar of the Obama administration’s rebalance to Asia. As Singapore Prime Minister Lee Hsien Loong recently pointed out in Washington, the United States might be able to push for a better trade deal bilaterally, but not many partners will be keen. His advice for the current U.S. administration are modest: “[D]o no harm. Don’t take steps which will damage the existing cooperation, the existing substantial trade and investment links which are already there.”

Meanwhile, Beijing has unfolded an ambitious vision for the region in the form of the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank and the Belt and Road Initiative linking countries in Asia, the Middle East, Europe, and Africa in a China-centered economic network. The 16-member Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership, which includes China but not the United States, is also moving forward. Although Trump’s phone calls to Asian leaders are often cited as examples of the United States engaging with the region, phone calls are not strategy and the region would not have failed to notice. Even if bilateral trade deals did eventually go through, U.S. leadership looks diminished in comparison.

No mean feat

President Trump thus has his work cut out for him in Asia. Insecurities about U.S. abandonment have been heightened by the president’s capriciousness in tearing up agreements; his casualness in questioning alliances; his threats of war with a country possessed of nuclear weapons; and his lack of enthusiasm in taking up his country’s traditional mantle of championing free trade (who can forget that U.S. officials opposed a reference to “protectionist trends” that could adversely impact global economic recovery and economic integration at an APEC meeting earlier this year). Trans-Pacific Partnership countries are still smarting from U.S. withdrawal when many had signed on notwithstanding painful domestic adjustments that the deal necessitates and objections from domestic constituencies. Restoring trust in the United States will take time and, even on Trump’s best behavior, is unlikely to be wholly restored on this trip.

Reassuring the region will also be made more difficult because of China’s strong showing. The recent Chinese Party Congress has further consolidated President Xi Jinping’s domestic position and supports a continued shift in the balance of power in the Asia-Pacific in China’s favor. The United States, on the other hand, appears weak at home and undecided about its proper role abroad. The indictments in special counsel Robert Mueller’s Russia probe are only the latest in a slew of scandals that have weakened the credibility of the Trump presidency. Divisions along multiple social lines are cleaving America’s broader polity. Asian societies place a premium on order. From this perspective, the United States looks, quite simply, a mess.

Still, the region remains the United States’ to lose. Many countries in Asia have enjoyed peace and prosperity secured by the U.S. presence and consider the superpower as having an important role to play in the region.

The region remains the United States’ to lose.

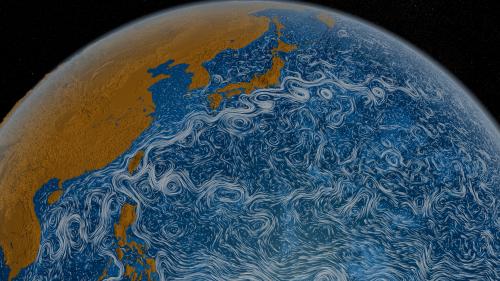

They are also wary about China’s intentions. Beijing’s attempts to assert greater de facto control in the South China Sea have not gone down well with neighbors. U.S. freedom of navigation operations, including four thus far in the Trump administration, have been a welcome push back against Beijing’s expansionist attempts and efforts to play fast and loose with international law.

At the end of the day, the region is pragmatic and will work with President Trump, whatever its personal views of him. (In this respect, a recent Pew Research Center Poll shows a “sharp decline” in how much U.S. allies in Asia have confidence in the president to do the right thing internationally.)

Trump’s top security and foreign policy officials have made trips to the region and statements that have been well-received. Secretary of State Rex Tillerson, for example, recently gave a strong speech calling for a “free and open Indo-Pacific” based on “shared commitment [to] upholding the rule of law, freedom of navigation, universal values, and free trade.” It will be incumbent upon Trump to flesh out his vision of how that goal is to be achieved on security, economic, and diplomatic fronts.

What’s at stake

Failure to convey a clear sense of what is at stake may mean that smaller countries in the region, regardless of reservations, will increasingly move into China’s orbit as a matter of necessity, if not choice. This would in turn have implications for the United States’ ability to defend its interests in Asia, the rule of law, and trade and investment standards. It would be the last thing putting “America First” needs. There would be no lack of irony if U.S. leadership and influence over Asia were to wane as the region’s importance waxes.

Commentary

High stakes but expectations are low for U.S. president’s first trip to Asia

November 7, 2017