At the start of the new year, alarms are again blaring over trade disputes between major economies, geopolitical tensions, and the potential for resurgent inflation. Yet, the global economy has remained surprisingly resilient for the past three years despite being subjected to a barrage of shocks. And there are at least three reasons why it could defy expectations yet again this year.

Let’s be clear: There is ample reason to worry. In the wake of elections in more than 60% of countries, policy uncertainty has reached its second-highest level in this century. New global trade restrictions introduced in 2024 were five times the average in the decade before COVID-19. Over 2025-26, in nearly two-thirds of economies, trade growth is on track to be lower than the 2010-19 average. Armed conflicts—interstate as well as intrastate—are occurring at a frequency not seen since the end of World War II. Global temperatures in 2024 were the highest on record, and weather-related disasters are dominating the headlines.

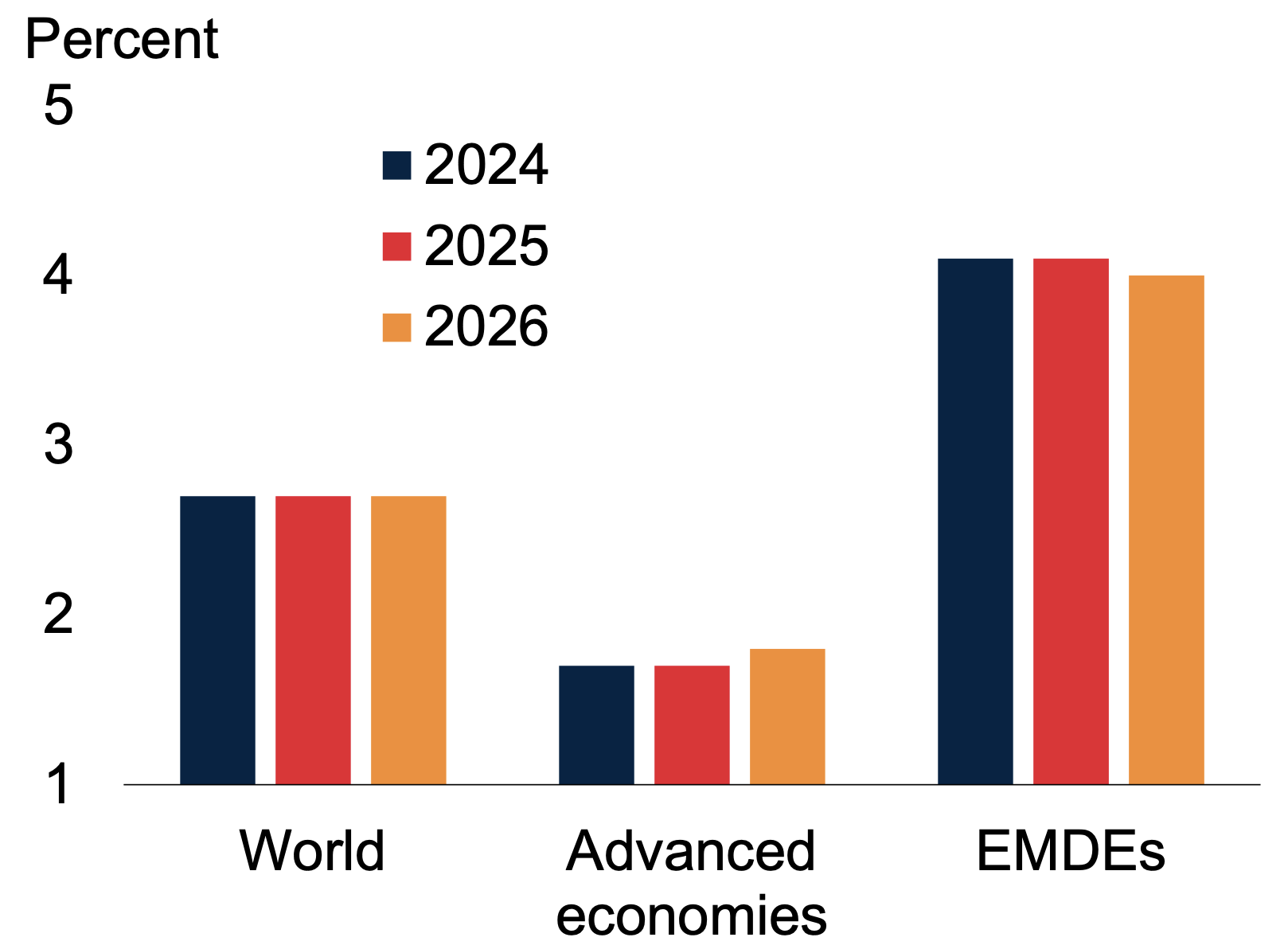

Figure 1a. GDP growth

Note: Aggregate growth rates are calculated using GDP weights at average 2010-19 prices and market exchange rates.

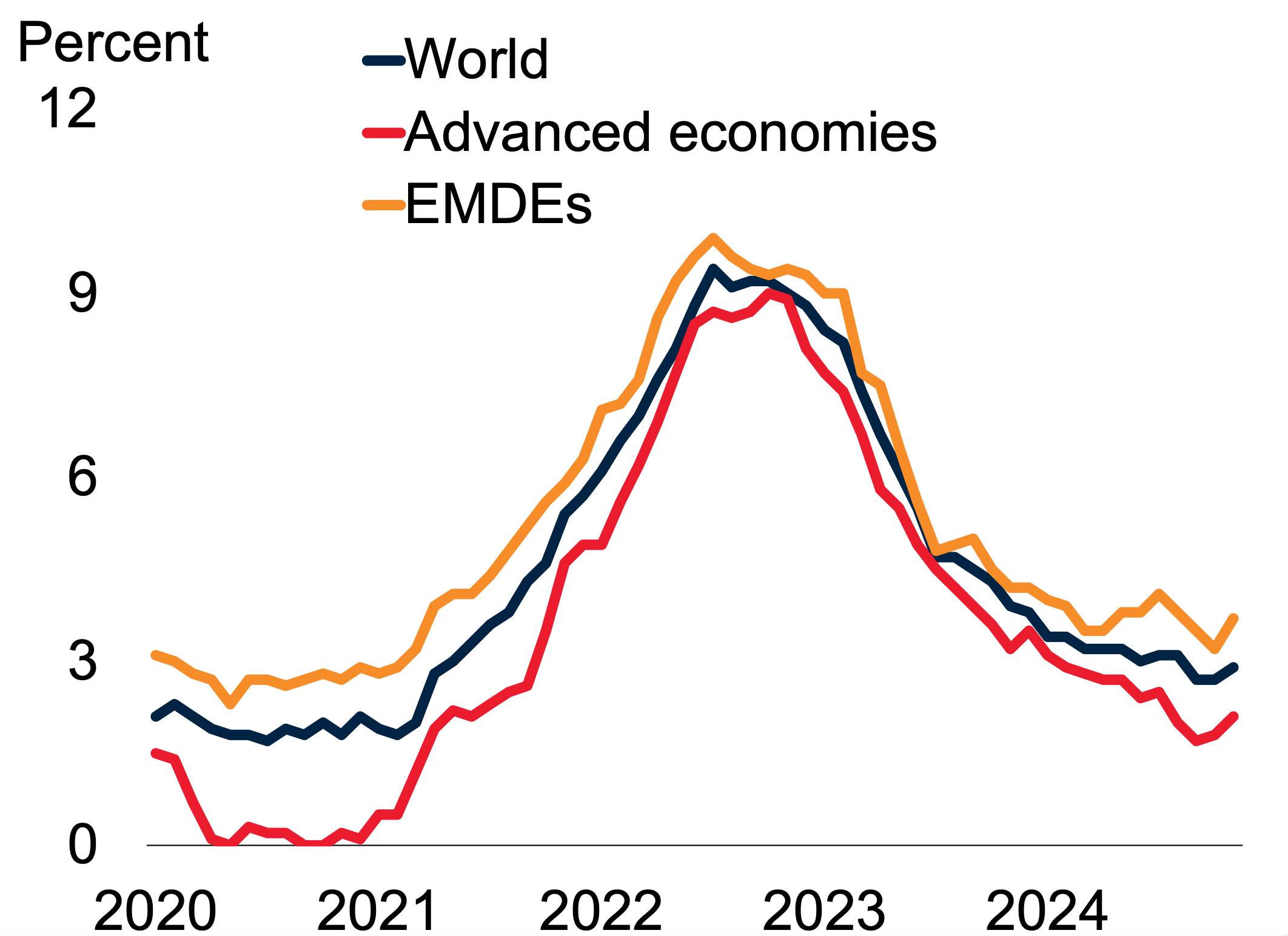

Figure 1b. Headline consumer price inflation

Note: The figure shows median headline inflation. Last observation is November 2024.

Yet it’s worth taking stock of what could go right in the near term—especially because the global economy has been resilient since COVID-19 in ways that puzzle most economists. The World Bank’s latest Global Economic Prospects report predicts that global growth in 2025-26 will clock in at 2.7%—the same pace as in 2024—as inflation cools and interest rates fall gradually (Figures 1a and 1b). That is remarkable in itself: It’s one of the few times central banks have managed to rein in high inflation without the economy falling into a recession. We see three possible surprises that could push global growth higher this year

Inflation might be whipped after all

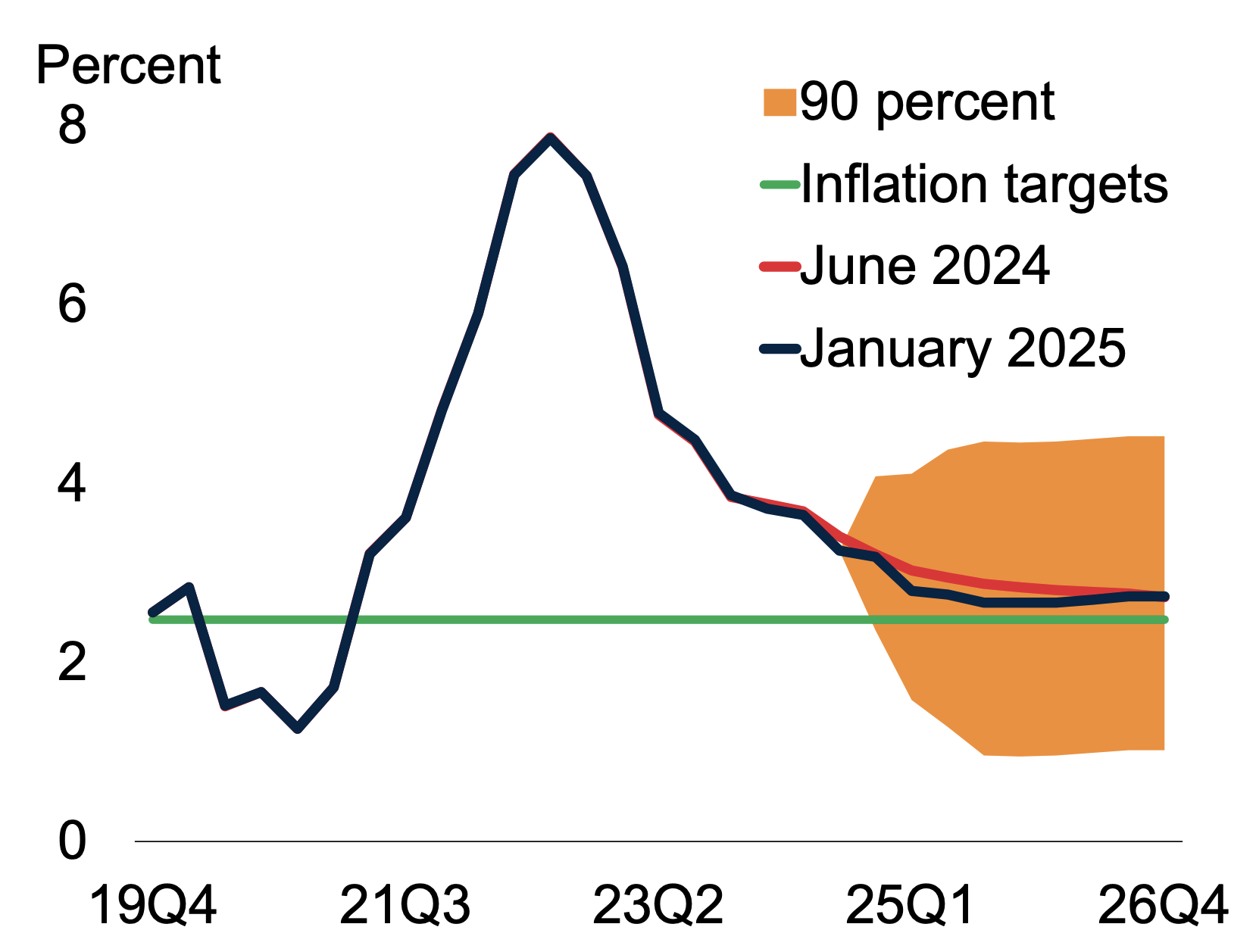

Our forecast calls for global headline inflation to fall to an average of 2.7% this year and next, bringing it close to levels that prevailed before COVID-19 (Figure 2a). But inflation could come down even faster if food and energy prices continue to decline.

We expect global commodity prices this year to fall to a five-year low amid an unusually large oil glut—once that has been surpassed only twice before: during the pandemic-related shutdowns in 2020 and the 1998 oil-price collapse. That would still leave overall commodity prices about 30% higher than they were in the five years before the COVID-19 pandemic, but it would nevertheless help ease pipeline inflationary pressures on the global economy. Lower food and energy prices would also ease strains on household budgets, improving prospects for real income growth. In addition, stabilization in freight costs and expanding manufacturing production in some countries could reduce import price inflation.

This potential for faster-than-expected global disinflation would enable central banks to cut policy rates more quickly than expected, boosting global demand and economic activity. Lower inflation and interest rates would be a particular boon to many developing countries currently facing high borrowing costs.

Figure 2a. Global consumer price inflation

Note: Model-based GDP-weighted projections of consumer price inflation using Oxford Economics’ Global Economic Model. The 90% confidence bands are derived from Consensus Economics forecast errors.

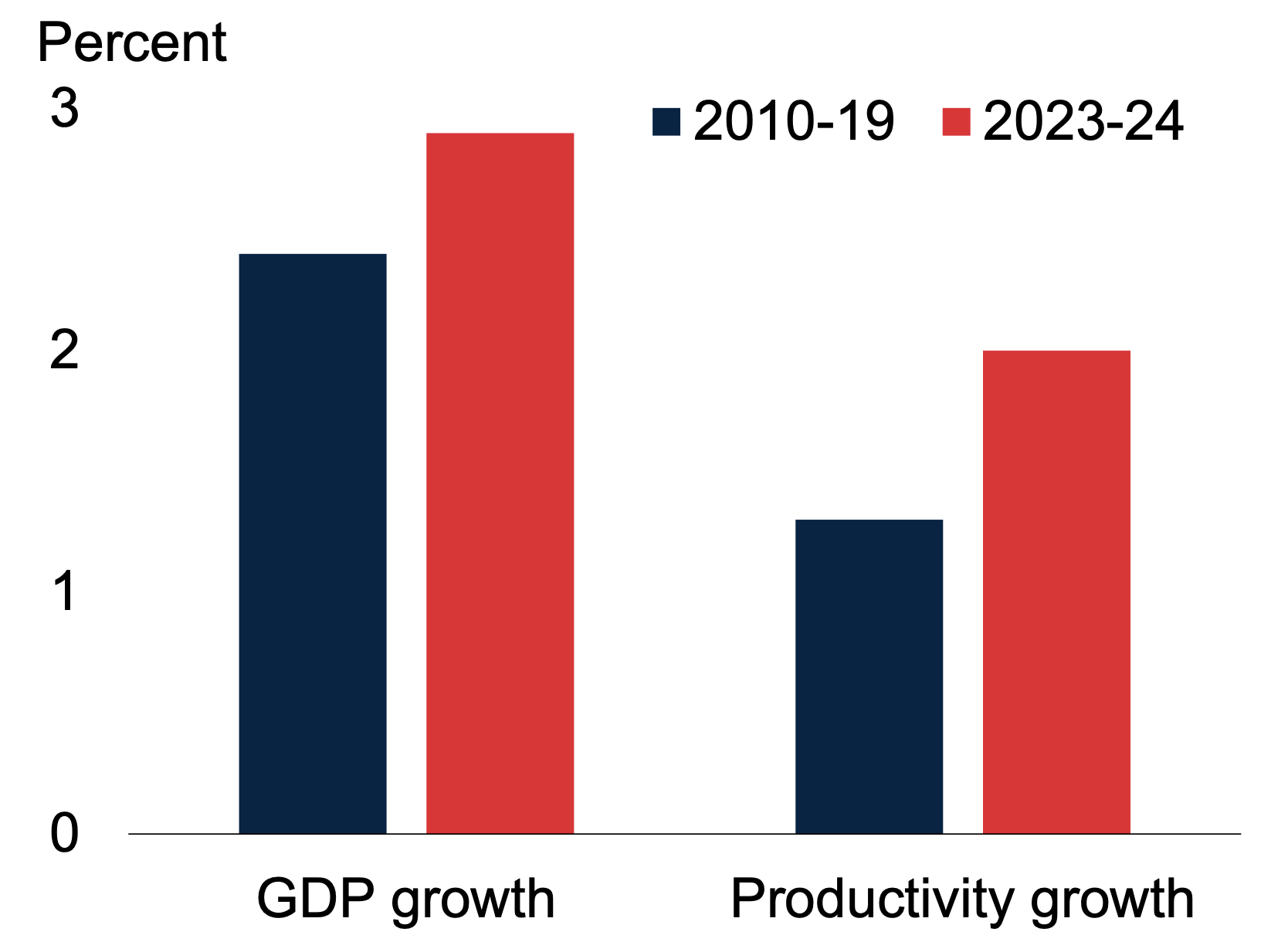

Figure 2b. GDP and productivity growth in the United States

Note: The figure shows year-on-year growth in quarterly GDP and nonfarm business output per hour. Data for 2023-24 covers 2023Q1 to 2024Q3.

The US economy delivers higher growth, again

On the basis of policies now in effect, our forecast calls for U.S. economic growth to slow modestly—from 2.8% in 2024, to 2.3% this year and 2% next year. The U.S. economic growth has surprised on the upside multiple times since COVID-19. It can do so again this year.

Our U.S. forecast assumes slowing income growth with cooling labor markets. However, U.S. labor markets and household consumption remain robust. A growth boost this year could also come from stronger U.S. productivity growth, which has surged since 2020 even as it has waned in many other countries. Since 2020, U.S. nonfarm business productivity has grown at an average rate of 1.9%—an acceleration of 0.6 point over the 2010-2019 average (Figure 2b).

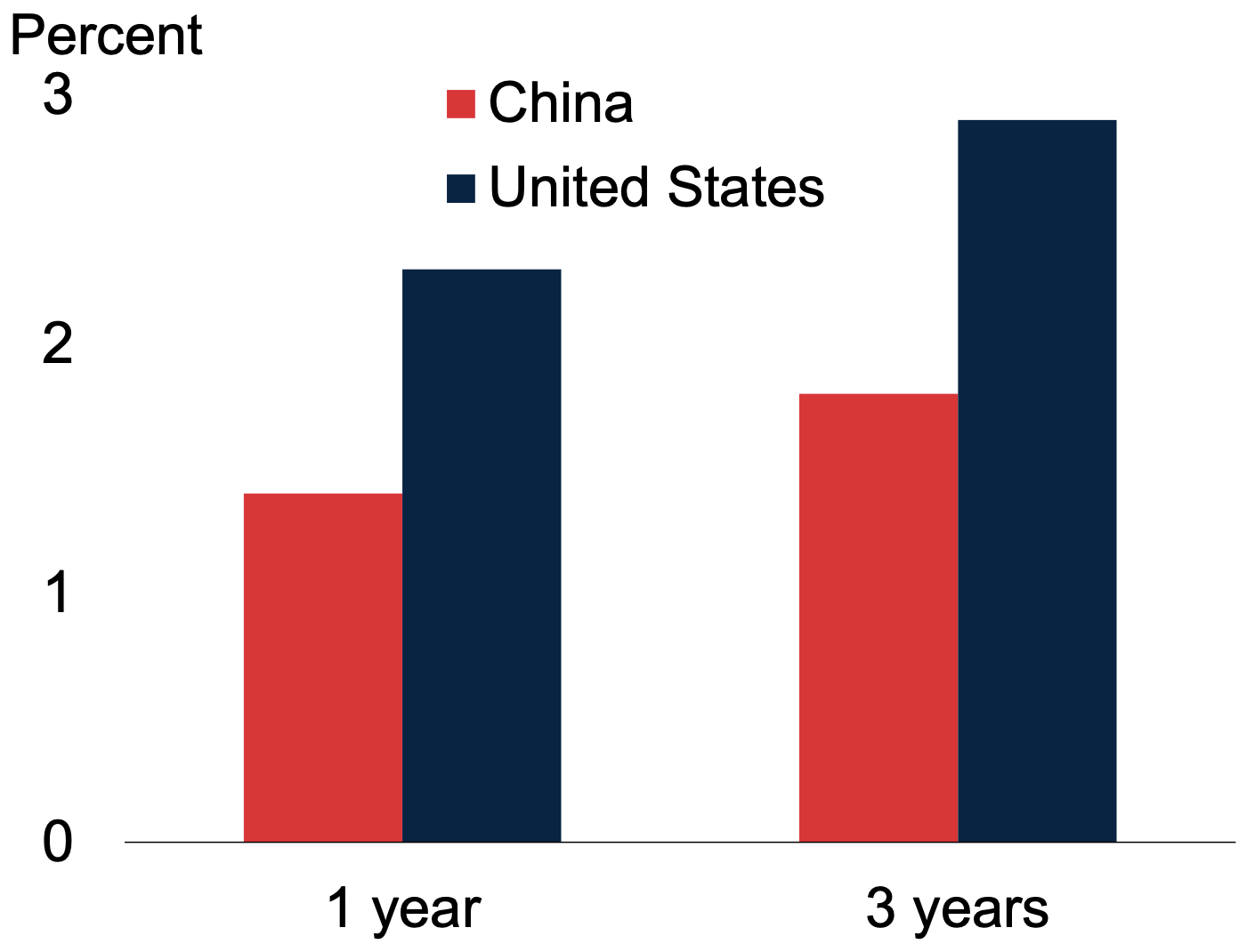

Stronger U.S. growth would have significant global spillovers. Our analysis suggests that a 1-percentage-point increase in U.S. growth tends to result in a nearly 3% rise in output of emerging market and developing economies after three years (Figure 3a).

Figure 3a. Impact of a growth increase in China or the United States on GDP in other EMDEs

Note: Median cumulative impulse responses of GDP in EMDEs excluding Brazil, China, and India, after 1 year and 3 years, to a 1-percentage-point increase in growth in China or the United States.

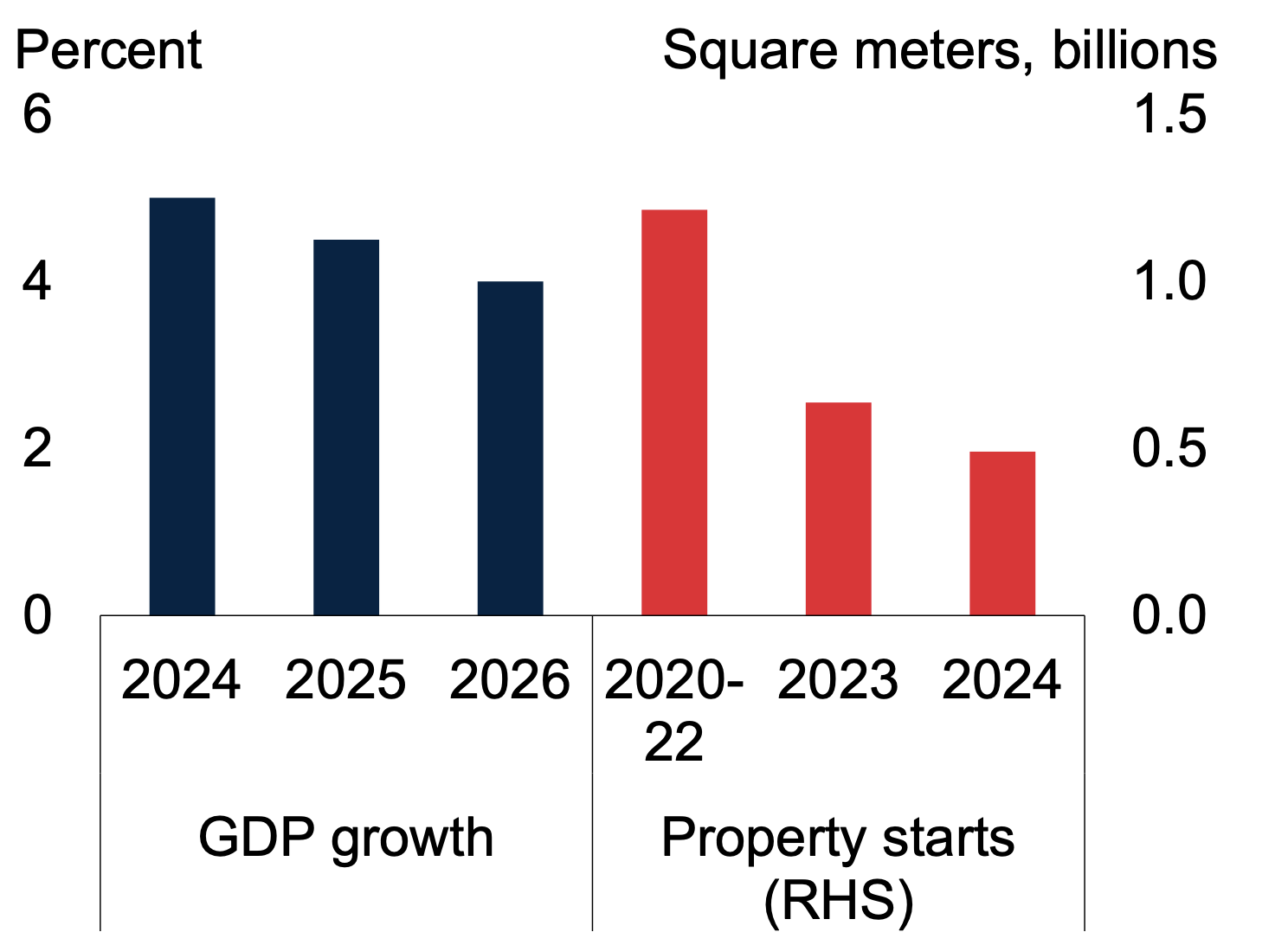

Figure 3b. GDP growth and property construction in China

Note: Property starts show year-to-date volume of residential building floor space construction commenced between January and September. Last observation is November 2024.

With policy support, China’s growth could be higher

We expect China’s economy to slow gradually over the next two years—from 5% in 2024 to 4.5% this year and 4% in 2026 (Figure 3b). In recent years, the government’s efforts to stimulate the economy have helped it to reach its growth targets. But policymakers there could opt for more aggressive efforts by undertaking structural reforms to stabilize its ailing property sector. China also has the policy room to provide more cyclical support to improve confidence and boost private consumption.

Strong growth in China could benefit its trade partners, especially emerging and developing economies that are commodity exporters. Our estimates suggest that a 1-percentage-point increase in growth in China could boost global GDP by a cumulative 0.8% over three years. The effects would be larger for countries that trade closely with China and are highly integrated into global value chains.

It’s possible to thrive despite the uncertain environment

None of this should be taken for granted: Over the next two years, much more could go wrong with the global economy than could go right. The economy’s current resilience, therefore, constitutes a crucial opportunity for many countries—emerging market and developing economies, in particular—to get their house in order while conditions remain favorable.

They can reap significant rewards by accelerating reforms to attract investment and deepen trade and investment ties with one another—and with all who seek to expand trade with them. They can help themselves by modernizing infrastructure, improving human capital, and speeding up the climate transition. In a nutshell, choosing the pragmatic route of pushing the policy frontier will pay far greater dividends than just yielding to pessimism or praying for good fortune.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).

Commentary

3 reasons the global economy could outperform expectations

January 27, 2025