False news travels faster than truth online. Incubated in online communities, mis- and disinformation often coalesce into conspiratorial narratives that receive higher, more sustained engagement on social media. Viral conspiracies can motivate individuals to engage in targeted harassment and violence that—while often aimed at elites—disproportionately affects marginalized populations.

Who is more likely to interpret events conspiratorially? Conspiracy theories are stickiest when they satisfy an individual’s underlying needs. Those with a strong need for closure or certainty, those facing threats to themselves or those close to them, and those seeking to maintain a positive image of themselves, their identity, or groups they belong to tend to gravitate toward conspiratorial interpretations. Previous research showed that highly knowledgeable people who also lack trust in governmental institutions are more prone to endorse political conspiracy theories, as are people who have been on the losing side of an election and are looking for a reason to keep holding onto their worldview.

Our new research, conducted with colleagues in the Center for Communication and Civic Renewal team at the University of Wisconsin-Madison, shows that how we approach our mediated world matters as well. We found that the way people do and don’t search for news online greatly affects their propensity to believe that a group of secret, malevolent actors are controlling the world. In short, people who avoid following the news because they think they will hear about the important stuff eventually are among the most likely people to think conspiratorially.

People encounter the news in a variety of ways. While some people omnivorously devour all the news they can and others prefer news from their ideological side, a considerable number of people choose not to look for the news at all, confident they can stay informed because if it is important enough the news will work its way into their interpersonal networks or social media feeds. People exhibiting high levels of this “news finds me” perception tend to have lower political knowledge and interest than others, and tend to use social media more often. Since previous research shows that those who are highly knowledgeable about, and distrustful of, the government are more prone to conspiracism, we wondered whether these media-use patterns and orientations toward news consumption contributed to a conspiratorial mentality as well.

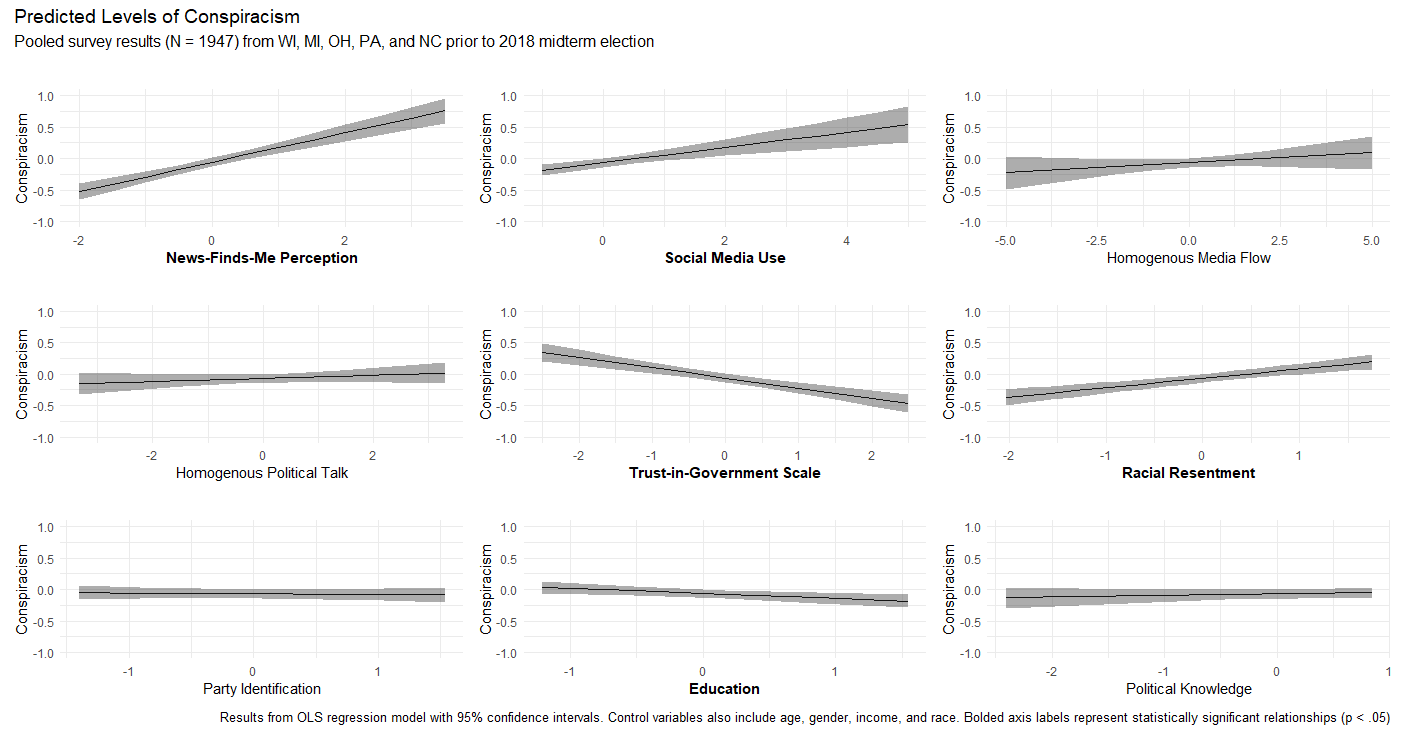

Does it? In a word, yes. We conducted a panel survey of adults in five 2020 presidential election swing states (Wisconsin, Ohio, Pennsylvania, Michigan and North Carolina), tapping people’s social media use, political interest and knowledge, trust-in-government, racial resentment, and whether they held a “news finds me” perception. The top-left panel of the figure shows that people with a higher “news finds me” perspective are the most likely to exhibit conspiracism in their thinking.

Using social media more often is also associated with more conspiratorial thinking, as is expressing high levels of racial resentment (by white people toward black people). Not surprisingly, the more people trust the government, the less prone to conspiratorial thinking they are. However, we found that party identification, political knowledge, homogenous political conversation and homogenous media-use patterns were not associated with conspiracism.

Believing in false conspiracies can happen to the knowledgeable but untrusting and those who are politically aloof but confident important news finds them anyway. As the figure shows, this is not a product of people living in partisan filter bubbles consuming politically slanted news content and talking only to those they already agree with. Those with a conspiratorial worldview use social media more and are more likely to have a “news finds me” perception. Communities, news outlets, and political elites will have to work diligently to temper these tendencies as voters sift through their news and social media feeds, making their 2020 electoral choices and forming preferences about how our country should be tackling its most pressing problems.

Jordan M. Foley is a Ph.D. candidate in the School of Journalism and Mass Communication at the University of Wisconsin-Madison.

Michael W. Wagner is Professor of Journalism of Mass Communication at the University of Wisconsin-Madison and the Director of the forthcoming Center for Communication and Civic Renewal.

Commentary

How media consumption patterns fuel conspiratorial thinking

May 26, 2020