The authors wish to thank Emily Skahill and Brady Tavernier for their research assistance on this report as well as external peer reviewers, who are subject matter experts, for their suggestions. A full methodological summary is available in Appendix A.

Executive summary

The Infrastructure Investment Bill and American Jobs Act (IIJA), passed in 2021, dedicates $65 billion for broadband funding and activities that close the digital divide. The monies are primarily being provided to states, localities and tribal communities who will determine how to allocate funding locally around the IIJA’s aspirational statutory goals. However, widespread data on where broadband assets exist throughout the U.S. are not widely available, leaving many states to creatively justify their use of federal funding. Without accurate depictions and data on how residents in rural, urban, and tribal lands are adversely impacted by the lack of available and sufficient high-speed broadband, certain populations will be left without sufficient online connectivity and remain on the wrong side of digital opportunities, particularly those populations already impacted by a range of historic and systemic inequalities throughout America’s rural South and Black Belt regions.

From May to June 2022, the Brookings Institution Center for Technology Innovation (CTI) contracted IPSOS Public Affairs (“IPSOS”) to poll 1,543 adults in the U.S. residing in the rural South about their access, use, and adoption of the internet and if they had broadband available to them on a regular basis. The result was a KnowledgePanel that drives CTI’s inaugural Rural Broadband Equity Project (RBEP) and informs relevant research for four papers that share the empirical findings. This first paper details the research background methodology and demographics of the Rural Broadband Equity Project, while further exploring who the rural respondents we interviewed believe is responsible for providing internet to their communities. Generally, lower-income rural residents expect the federal government to intervene and incentivize private companies to accelerate broadband deployment, and they are looking to their states and localities to embolden community-based organizations and other anchor institutions to assist in their endeavors. Given the urgency and magnitude of the recent IIJA investments, states and localities must not only effectively narrow digital disparities that impede on universal broadband in rural areas but also address the broader economic and social vulnerabilities of these residents. In our study, we find that people from historically disadvantaged communities, especially Black and Hispanic populations that lack internet access, are subjected to consistent and perpetual inequalities. Most notably, poverty and the restriction of opportunities in education, employment, health care, entrepreneurship and more are prohibiting their access to improved quality of life. Being subjected to the digital divide has added to the existing inequalities of some rural residents, making it imperative that states, localities, and tribal lands ensure that the goals of the IIJA serve the least connected communities first. Without such diligence, the U.S. will continue to leave millions of Americans disconnected, especially those already restricted in their economic and social mobilities.

Introduction

Federal and state local legislators, in addition to other appointed leaders, are working quickly to accelerate high-speed broadband access and adoption for residents in the United States. The enactment of the historic Infrastructure Investment Bill and American Jobs Act (IIJA), passed in 2021, provides $65 billion for broadband funding through four programs overseen by the National Telecommunications and Information Administration (NTIA) in the U.S. Department of Commerce. The IIJA aims to close the digital divide, which is defined as not just a lack of access to “affordable, reliable, high-speed internet access,” but of equipment, digital skills, financial resources and more as well.1 The recent congressional action also signals that the digital divide is increasingly worsening for certain populations, especially those from “communities of color, tribal residents, and [people from] lower-income areas” in urban and rural areas.2 Further, the legislation works to prevent “digital discrimination of access based on income level, race, ethnicity, color, religion, or national origin,” ensuring “equal access to broadband internet access service”.3 The Federal Communications Commission (FCC), the sister agency to NTIA on the IIJA, has been charged by Congress to provide additional guidance on the definition of such discrimination. The specific statute, coupled with the sizable appropriation amounts, affirm that the U.S. urgently aspires to equitably narrow digital disparities. But questions remain on whether the constituents who require support from the federal government will directly benefit from the political goodwill.

The NTIA and FCC are not the only federal agencies advancing more ubiquitous broadband deployment on the supply side. The U.S. Department of Treasury has recently announced a series of investments earmarked for network infrastructure, which essentially adds to the available monies invested in high-speed internet service. With these massive and complementary investments, CTI researchers begin our series with more granular questions of who rural residents think is accountable and responsible for deploying high-speed broadband in their communities, and whether the current funding mechanisms are effectively deterring digital isolation.

Bringing high-speed broadband solutions to rural America is a large part of the infrastructure package, especially among communities desperately underserved by existing government programs and incumbent internet service providers (ISPs).

There is no question that technology has become more available and affordable for most Americans at all socioeconomic levels.4 The global pandemic surfaced both the importance and availability of online connectivity as millions obliged the calls for physical social distancing and transitioned online for remote work, school, health care, government services, and regular communications with friends and family members. Yet, millions of other people still struggle with sustaining consistent access to broadband internet, especially low-income and rural populations. Where one lives also matters when it comes to the quality of their digital life, with more rural populations experiencing disconnects compared to urban populations in both online access and quality of life. At the pandemic’s peak, vulnerable populations were restricted from various tasks, such as applying for unemployment benefits, engaging in distance learning, or scheduling and receiving vaccinations due to a lack of online access.5 Rural residents were more likely to be impacted by the disruption in their access to these very basic functions, and as a result, experienced higher rates of COVID-19 deaths due to the medical and social isolation they experienced before and throughout the pandemic.6

Further, rural areas have recently seen increased migration of people of color. Between 2010 and 2020, the population of color in the median rural county increased by 3.5 percentage points, and by 2020, people of color accounted for 10 percent of the population in two thirds of rural counties while 10 percent of rural counties had a majority population of people of color.7 Despite these population shifts, rural residents are also facing dire economic outcomes compared to their urban counterparts. According to the 2019 American Community Survey (ACS), the rural poverty rate was 15.4 percent, compared with 11.9 percent in urban areas.8 The geographies with the most severe levels of poverty are in the southeast, where our project is focused, and on Native American lands.9 Black people living in rural areas had the highest incidence of poverty (30.7 percent) in 2019, while Native Americans in rural areas had 29.6 percent, and Hispanics in rural areas had 21.7 percent.10 Compared to only 11.3 percent of whites living in rural areas who face poverty, the percentages of communities of color impacted by poverty in rural communities are far higher.11Bringing high-speed broadband solutions to rural America is a large part of the infrastructure package, especially among communities desperately underserved by existing government programs and incumbent internet service providers (ISPs). More specifically, the legislation emphasizes the importance of prioritizing build-out and deployment in these areas, and goes as far as setting speed guidelines for locations by ranking projects higher if they target areas that are “unserved,” with under 25 Mbps downstream and three Mbps upstream (or 25/3 Mbps) broadband speeds.12 The complementary State Digital Equity Capacity Grant and Digital Equity Competitive Grant Programs allocate $1.44 and $1.25 billion respectively for unserved areas with covered populations, referring specifically to a list of minority populations including: aging individuals, incarcerated individuals, veterans, individuals with disabilities, individuals with a language barrier, individuals who are members of a racial or ethnic minority group, and individuals who primarily reside in a rural area.13These combined activities and attention to narrowing digital disparities make the path toward more universal broadband access easier than in years past, especially for rural residents. Yet, how the IIJA gets executed and to whom the funds get distributed matters, particularly for communities where broad strokes of other systemic inequalities exist, such as persistent poverty and inadequate access to housing and health care. With states, localities, and tribal lands primarily leading the planning and implementation of IIJA funds, it is imperative that they not only better understand the needs and wants of all their constituents when it comes to broadband internet but that they also start with the hyper-local concerns of their populations, especially those who are set to improve their quality of life through more robust online connections.

There has been a pattern of rural broadband development

Historically, policymakers have taken wholesale policy and funding approaches when it comes to alleviating digital constraints in rural areas, which has resulted in overspending in areas with minimal or no impact in broadband deployment and adoption. Even with sizable investments among rural carriers, these communities have either been vastly underserved or subjected to less competition, which has inflated pricing for subscribers. Further, it has been harder to measure the effectiveness of these programs due to the lack of robust information about these populations, especially those who have been marginalized due to rapid declines in farming and stagnant employment.14 With the NTIA executing the congressional infrastructure mandate, we share the preliminary results of the inaugural “Rural Broadband Equity Project” (RBEP), which is a survey of more than 1,500 residents from what was popularly coined as the Black Belt of the U.S., a specific reference to former cotton plantations that were historically controlled by whites and cultivated by former slave labor. The derogatory and discriminatory assignment of the land has resulted in concentrated poverty, disinvestment, and, in some instances, social isolation of residents who now consist of Black, Hispanic, and tribal households since the dismantling of segregationist laws.

This paper is the first of four that unpacks how rural Americans are navigating the availability of online access in rural areas and focuses on the lives of Black and Hispanic populations, who have historically experienced the intersection of various inequalities due to race, class, and geographic residence.

Focusing on the recent congressional actions of the IIJA and the urgency among states and localities to lead the charge for greater broadband deployment and adoption, the authors focus on who rural residents perceive as accountable and responsible for advancing community broadband needs and whether the current policy and programmatic objectives will help them attain these needs and wants when it comes to engagement in the digital economy.

Description of the Rural Broadband Equity Project

Over the months of May and June 2022, CTI contracted IPSOS Public Affairs (“IPSOS”) to poll 1,543 adult Americans living in the rural South, including an oversample of 300 Black and 300 Hispanic adults, about their access to and use of the internet, as well as how high-speed broadband internet (or lack thereof) impacted the quality of life in their households and the rural communities they lived in. Working with IPSOS, Brookings designed a survey instrument touching upon a variety of consumer- and community-facing outcomes. In particular, the survey instrument focused on how rural area residents currently use their online connections, if available. Our research also explored what these same residents aspire to do when sufficiently connected to robust internet.

Federal definitions of rural

Official definitions for “rural” vary, with populations ranging from 2,500 to 50,000.15 The most used rural definition refers to the “2,050 nonmetropolitan counties lying outside metro boundaries,” with metro areas defined by the Office of Management and Budget (OMB) as “core counties with one or more urban areas of 50,000 people or more” and outlying counties economically tied to these core counties.16 Various programs also differ in their definitions of rural. For the USDA’s Telecom Hardship Loan Program, rural is defined as areas with less than 5,000 people.17 Meanwhile, the Rural Health Care Program (RHC) follows the definition of “rural area” established by the FCC, which refers to areas that “do not have an urban area or urban clusters with a population of 25,000 or greater.”18For the purposes of this paper, we define rural areas based on the 2020 Census Planning Database, which uses urban/rural data from the 2010 paper. The Census Bureau identifies two types of urban areas and considers everything else as rural. The two types are (1) Urbanized Areas (UAs) of 50,000 or more people and (2) Urban Clusters (UCs) of between 2,500 to 49,999 people.19

State distribution

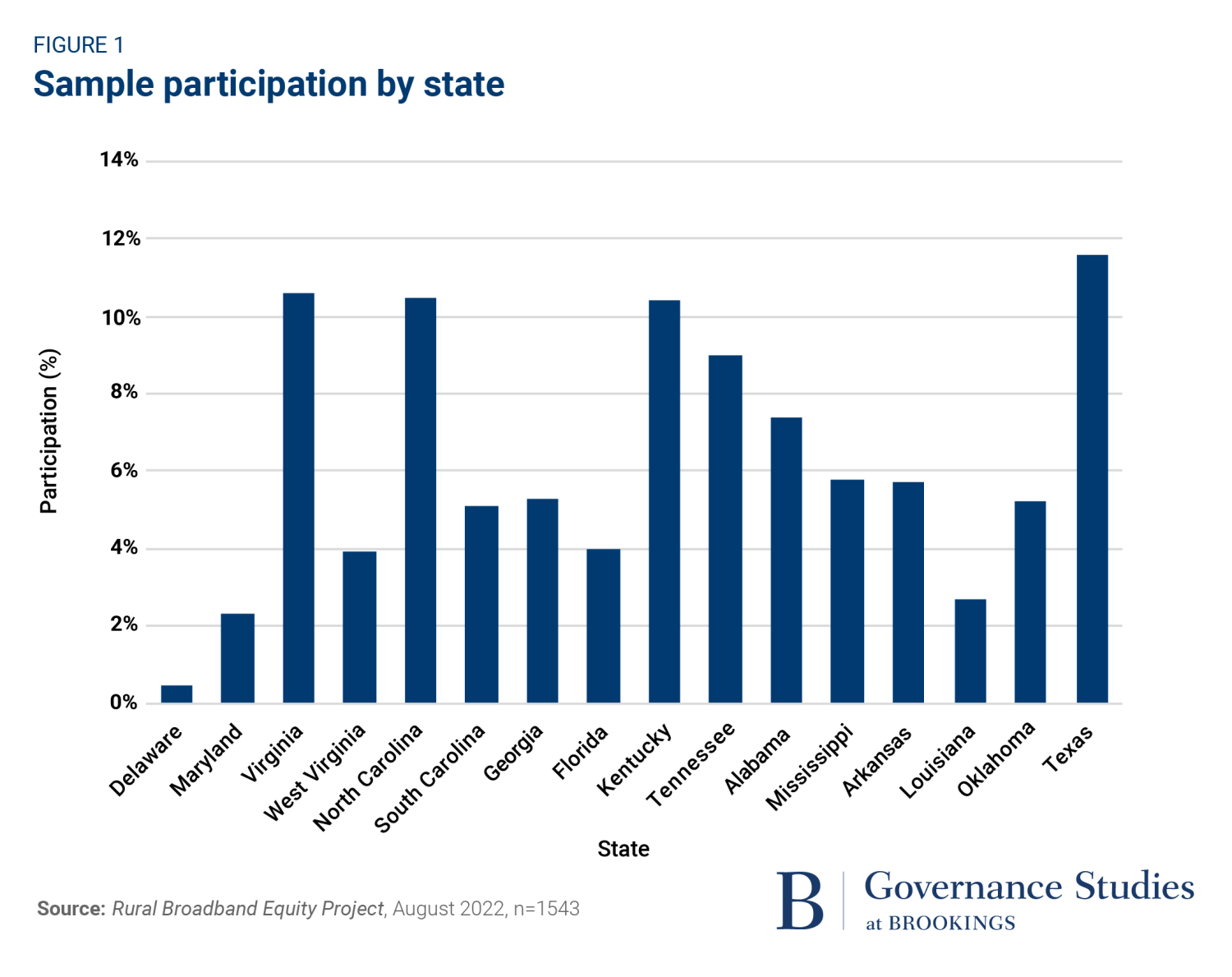

Residents from tribal lands were not included in the study due to the research’s focus on the Black Belt region. To target only rural areas—rather than any ex-urban areas close to suburbs—our population of interest was defined to only include zip codes in the rural South (the Census South region) where the 2010 U.S. Census had determined at least 99 percent of the population lived in a rurally-designated area; that is, an area which is neither urbanized nor an urban cluster.20 These areas are defined by a complex mixture of factors but are mostly based on population density per square mile, as well as the distance to the nearest previously-defined urban area.21 In our study’s case, this included 11 million people spread across 5,589 zip codes and 16 states after removing zip codes with a population of zero. Demographically, these zip codes were overall majority white; the Black population made up 11 percent of the population of interest, and the Hispanic population made up just over two percent of the population of interest. Each zip code had an average of 2,000 people and a median of 1,200 people contained within it. The states with the largest fit to the prescribed demographics are shown in Figure 1.

The sample

There are 1,543 total respondents included in the study. Each of the respondents surveyed was an English-speaking adult who was living in a zip code meeting the above criteria. IPSOS also established an oversample of 300 Black non-Hispanic and 300 Hispanic participants, bringing the unweighted demographic totals in the final survey to over 400 Black non-Hispanic and over 350 Hispanic participants. The overwhelming majority of the remaining respondents self-reported that they were white and non-Hispanic, which aligns with national demographic data for these states and zip codes. Appendix One provides more detail on the methodology.

Poll limitations

To ensure a representative sample, IPSOS hosts a comprehensive pre-existing panel—KnowledgePanel, the largest online panel that is representative of the U.S. population. Respondents are recruited using an address-based sampling methodology derived from United States Postal Service database files. To ensure that KnowledgePanel includes all randomly selected households, no matter their phone or internet status, IPSOS provides tablet devices with cellular non-broadband internet service included to households without consistent internet and device access, though this is rarely needed. To reach our population of interest, IPSOS administered the survey on 933 KnowledgePanel participants, as well as 610 opt-in panel participants. In the case of our sample, less than five percent of respondents received a device from IPSOS, and less than two percent of respondents reported using an IPSOS device with no additional household internet connection.

As a result of the construction of KnowledgePanel, all respondents have at least limited access to the internet through both a device and a slow non-broadband internet connection to complete the text-based online survey. As such, while this poll should not be used to inform about the interests, experiences, and needs of those without any form of internet access, it does serve as a window into how those in the rural South with access to at least slow internet feel about their connection, as well as insight into who they believe is responsible for improving internet access in their communities.

Results validation

To additionally validate our population-representative sample, we compared results of broadband access from our rural South survey to previous surveys conducted on internet access in rural America from the ACS and the Pew Research Center (“Pew”). Approximately 72 percent of rural residents surveyed by Pew in early 2021 reported that they had access to a broadband internet connection at home; similarly, the 2018 ACS found that 7 percent of those in rural areas in the Census South region had access to a broadband subscription.22

The RBEP consists of the new empirical data, and four White Papers, including this first one, which focuses on how rural residents position accountability when it comes to broadband deployment.

These are three and eight percentage points higher, respectively, than the results found in this poll (70 percent of respondents), which used identical response options to the ACS poll but instead asked, “Which of the following does your household, including you, use to access the internet service at your home, excluding smartphones or mobile device hot spots?” In contrast, the ACS poll asked, “Do you or any member of this household have access to the internet using a —[.]” While the difference between Pew and our own poll are statistically indistinct, the differences between the ACS’s and this poll’s numbers merited additional comment. We feel that differences in the wording of the two questions—both in prompting use and excluding smartphones/hotspots—likely explain the discrepancy between the two findings, though broadly speaking both results do appear to be comparably sized. For additional comparison, the authors note that Pew also uses IPSOS for its broadband research and refers to its use of the KnowledgePanel approach in their recent studies.23

The project deliverables

The RBEP consists of the new empirical data, and four White Papers, including this first one, which focuses on how rural residents position accountability when it comes to broadband deployment. Future papers will focus on the role of local anchor institutions, specific engagements, and activities by rural residents of color and the types of economic and social opportunities present when broadband is sufficiently deployed and adopted.

Additionally, our research will soon be complemented by a series of qualitative narratives from a range of rural residents, who understand the implications of being on the wrong side of digital opportunities. Brookings partnered with Rural Rise, a non-profit organization based in rural West Virginia, to assist in the identification and interviewing of people who stand at the intersection of rural poverty and digital invisibility.

Why the U.S. continues to lag in closing the rural digital divide

The FCC claims in its most recent report that as of 2019, only 4.4 percent of Americans do not have access to broadband, while 17 percent of Americans in rural areas and 21 percent of Americans living in tribal lands lack access to broadband.24 However, many academics and organizations disagree with the FCC’s maps, since providers independently report the data and can report that they are serving an entire area if they are only serving one customer.25 On the other hand, other studies have found that 50 percent or more of rural America lacks access to a broadband connection.26When race and ethnicity are factors in measurements to determine who is online, people of color are amplified as they have generally fallen further behind in the digital divide—stricken by other systemic inequalities. For example, according to the 2018 ACS released by the U.S. Census, 34 percent of American Indian households with children and 31 percent of Black and Hispanic households with children lack access to home broadband, compared to 21 percent of white households with children.27 A 2016 study found that 52.1 percent of the Hispanics population, 44.6 percent of the Black population, and 67.1 percent of the Native American population in rural areas lacked any access to broadband speeds of 25 Mbps download and that “after controlling for income, education, age, and other factors, the marginal impact of race/ethnicity on household-internet adoption is -5.6 percentage points for Hispanics, -8 percentage points for Blacks, and -5.5 percentage points for American Indian/Alaska Natives, relative to Whites.”28

When broken down by geography, the lowest rates of rural broadband availability regionally are in the South,29 and the South has the greatest divide in access to broadband between urban and rural areas.30

These data highlight that, on top of how economic difficulties disproportionately affect communities of color and limit their access to broadband, racial and ethnic background can further correlate with who is connected. When broken down by geography, the lowest rates of rural broadband availability regionally are in the South,31 and the South has the greatest divide in access to broadband between urban and rural areas.32

The Joint Center for Political and Economic Studies recently reported that in the rural Black South, defined by states designated as “rural” by USDA and populations that are at least 35 percent African American, 38 percent of African Americans report that they lack home internet access compared to 23 percent of white Americans in the rural South. That is a 15-point difference, compared to the 4-point difference nationwide.33 Data from the Pew Research Center shows similar disparities in home broadband access for communities of color: 80 percent white adults report having home broadband, in contrast to only 71 percent of Black adults and 65 percent of Hispanic adults. Additionally, 63 percent of Black adults say not having high-speed internet puts people at a major disadvantage when it comes to connecting with doctors or other medical professionals. Conversely, only 49 percent of white adults say the same.34

The next section presents an overview of the sample before delving into who they perceive as responsible for ensuring universal broadband access in their communities, especially among Black and Hispanic populations. The paper concludes with a series of recommendations that states and localities should prioritize in their current efforts to build capacity and drive the design and implementation of their specific broadband projects.

Overview of the research sample

Given the specificity of the zip codes and targeted states, respondents were more similar than different across the participating states. The sample also mirrored some of the more predominant demographic classifications seen in other broadband datasets, including by race, ethnicity, income, and educational levels, among other characteristics.

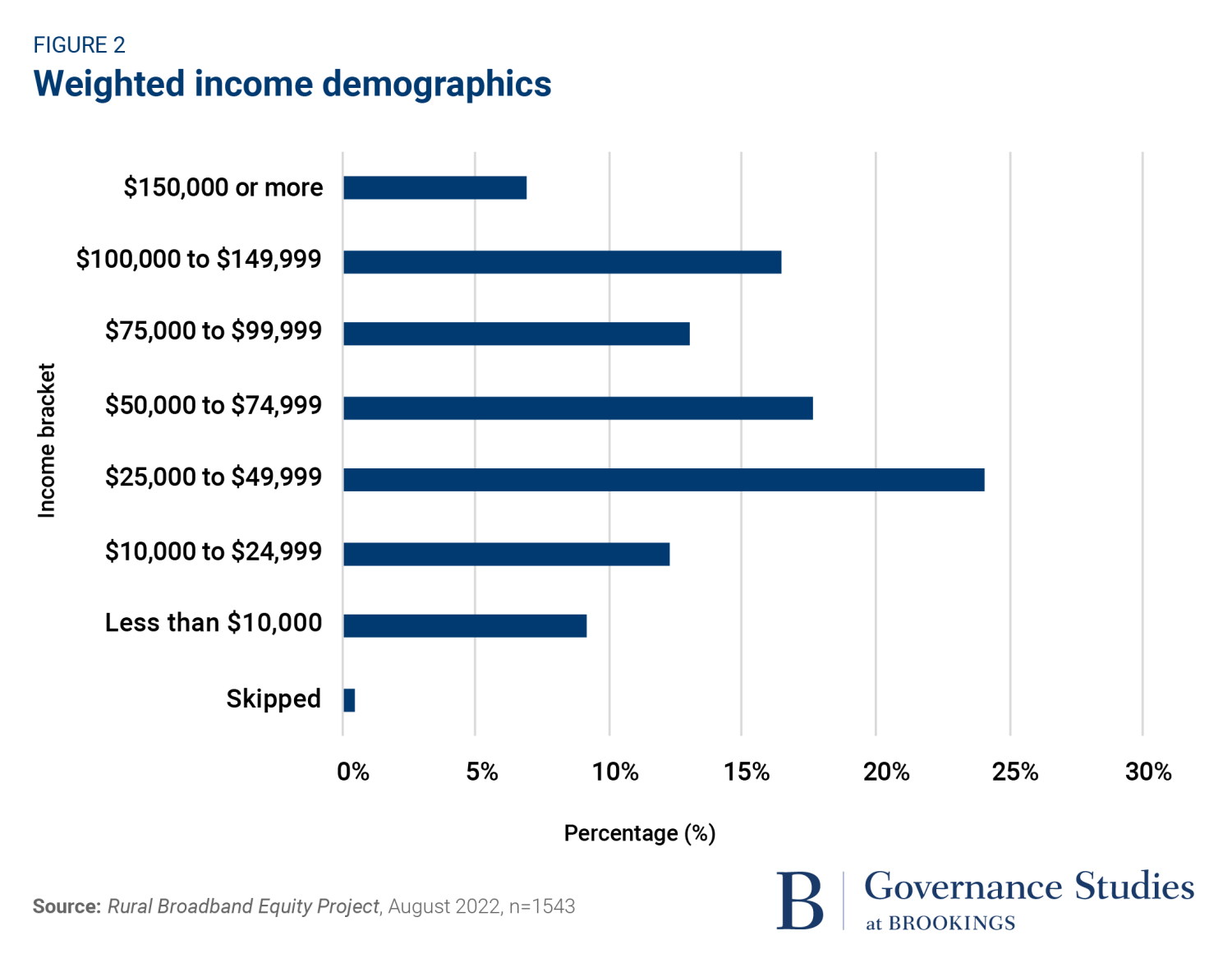

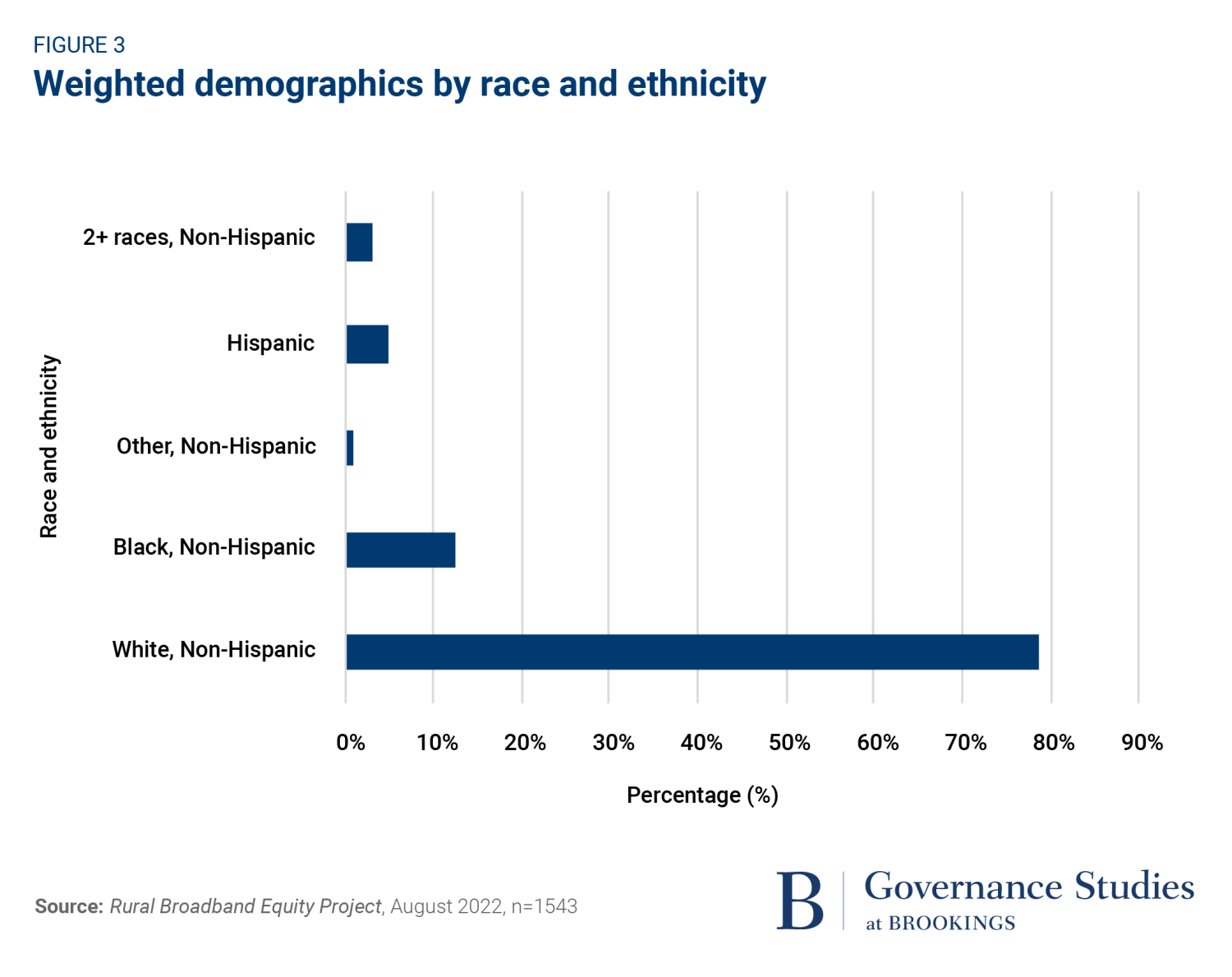

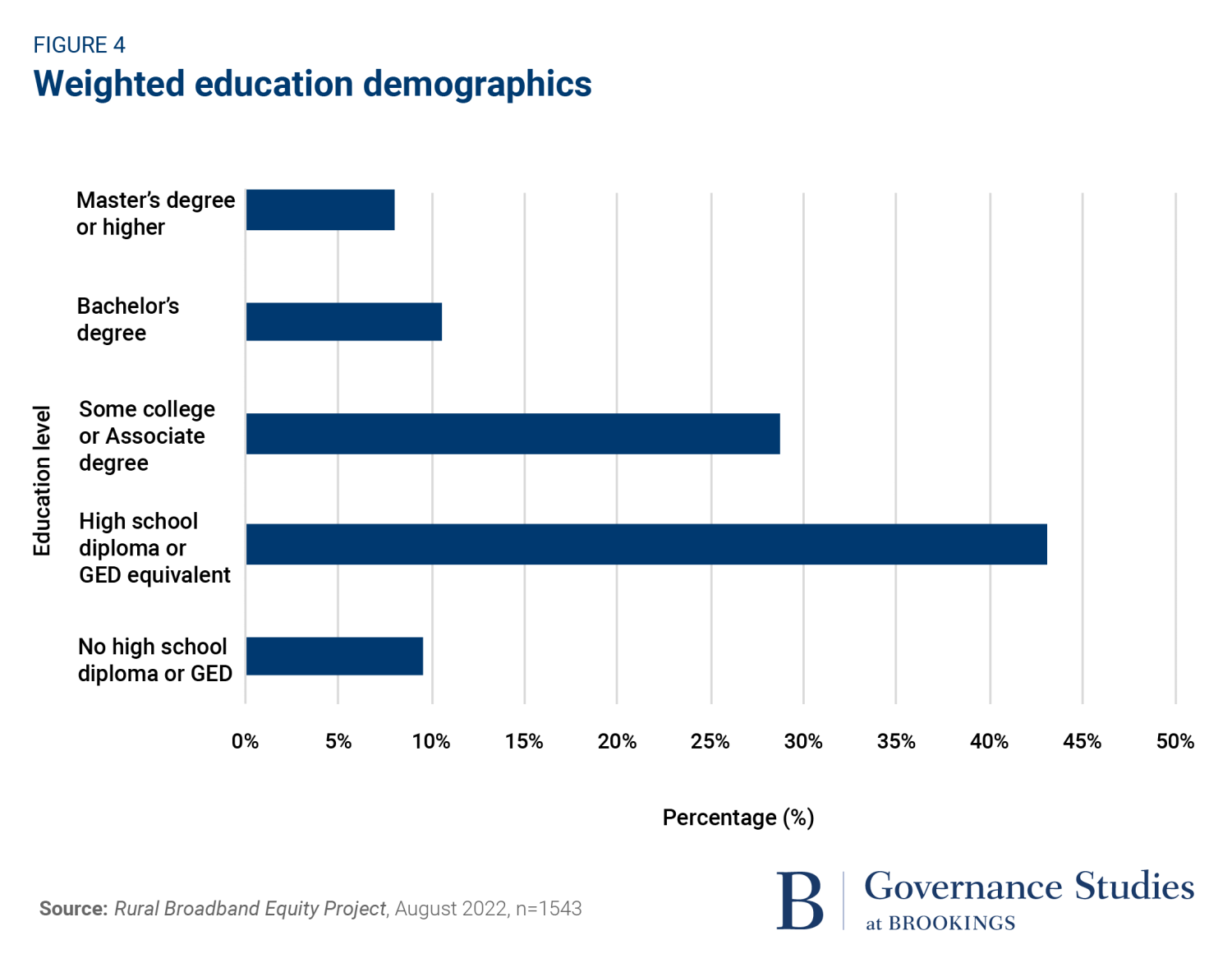

Generally, respondents were largely white (78.7 percent), with Black and Hispanic populations making up a significant percentage at 12.6 percent and 4.8 percent of respondents, respectively. The median annual income was $50,000 to $74,999, while the greatest percent of respondents made $25,000 to $49,999 annually. Most respondents were high school graduates (43.1 percent), but a significant portion also had some degree of college education: 28.7 percent had some college or an associate degree, 10.6 percent had a bachelor’s degree, and eight percent had a master’s degree or above.

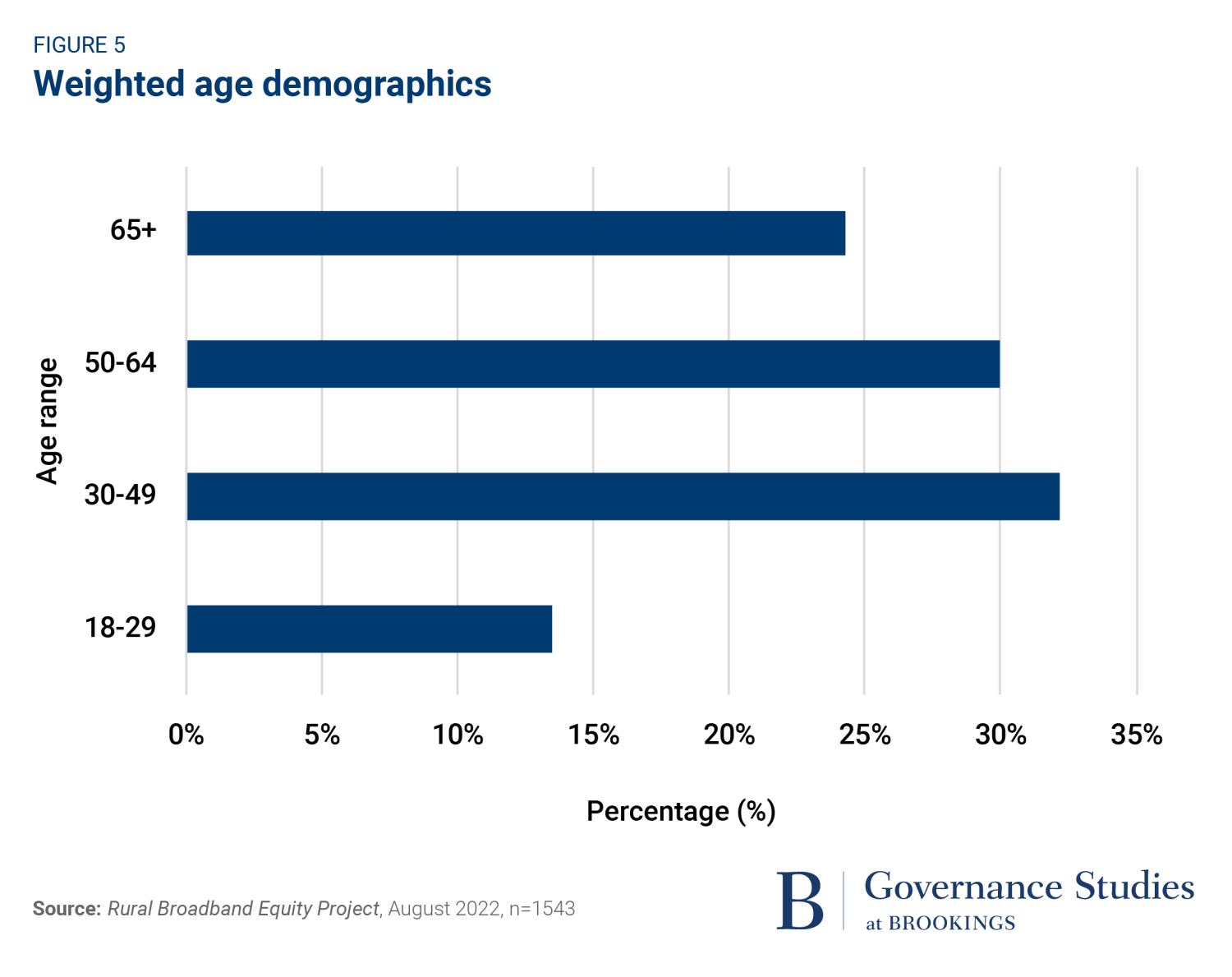

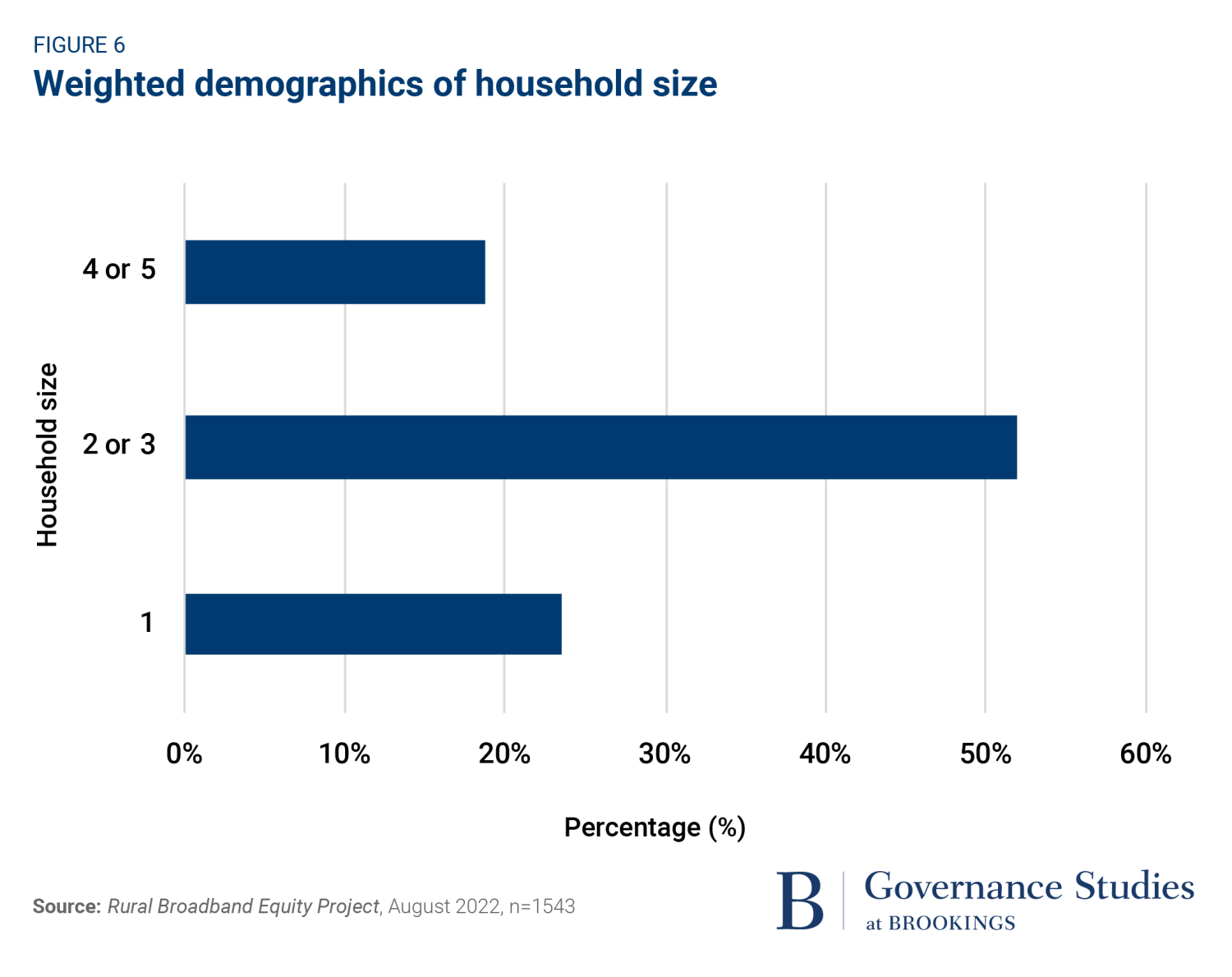

There was a slight overrepresentation of women: 59.9 percent of sample respondents were women, while 40.1 percent were men. Additionally, only 13.48 percent of respondents were between the ages of 18 and 29, while the median age was 50 to 64 years old. Households with children were also largely representative of sample respondents; over 50 percent reported having two to three children under the age of 18.

Figures 2 through 6 offer visual summaries of the study’s demographic breakdowns.

Access to the internet

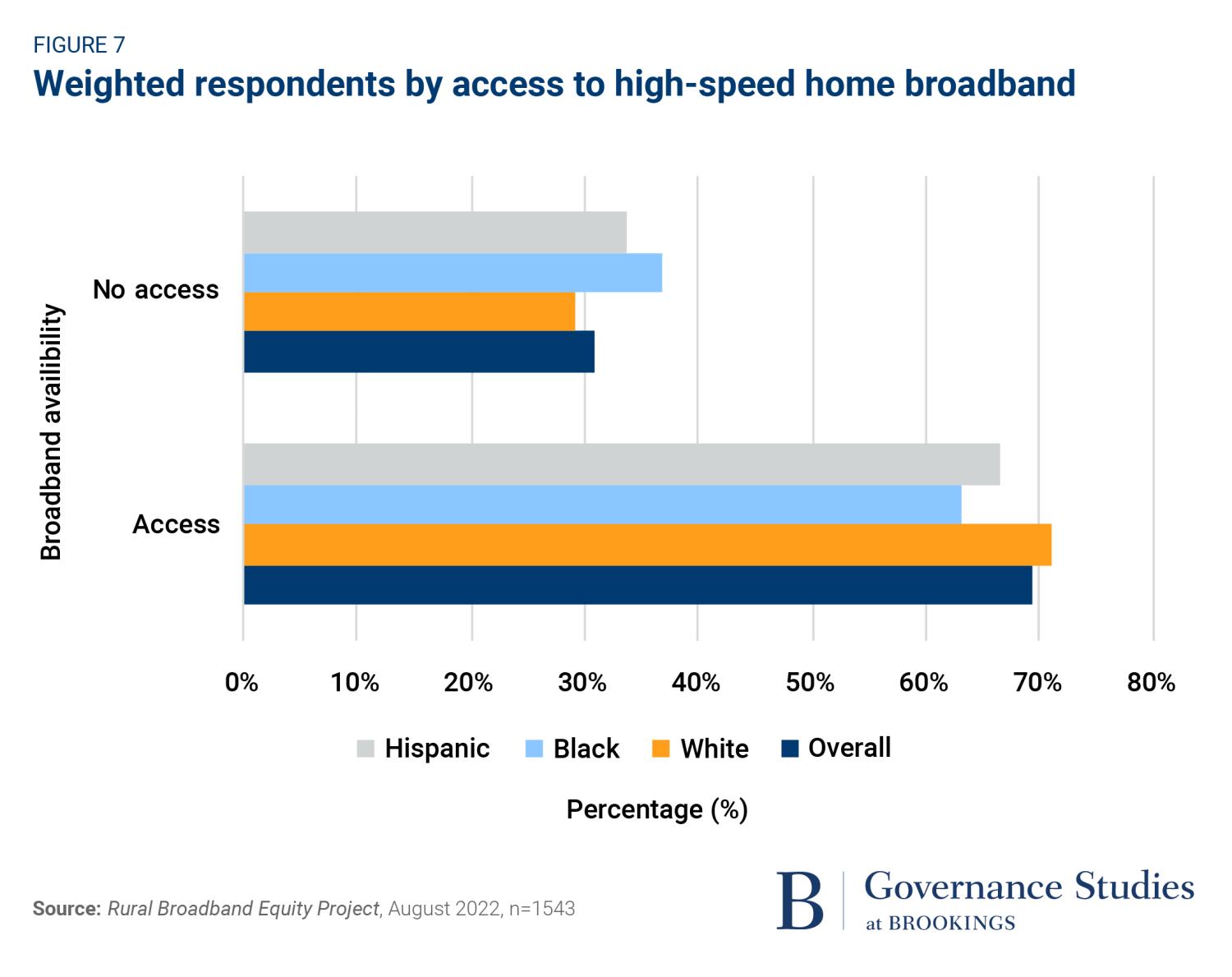

Study respondents were also largely connected to some type of internet due to the poll limitations of the KnowledgePanel (see notes in Methodology section). While most respondents reported access to high-speed broadband (69.2 percent), 30.8 percent did not. To measure access to home broadband, we asked respondents if they used high-speed broadband internet service, such as DSL (Digital Subscriber Line), cable, fiber optic, dedicated fixed wireless, or other services to access internet service at home. We also asked respondents to measure what percent had access to dial-up internet service (4.2 percent) or satellite internet service (8.5 percent). (See Figures 7 and 8.)

Access to the internet

Study respondents were also largely connected to some type of internet due to the poll limitations of the KnowledgePanel (see notes in Methodology section). While most respondents reported access to high-speed broadband (69.2 percent), 30.8 percent did not. To measure access to home broadband, we asked respondents if they used high-speed broadband internet service, such as DSL (Digital Subscriber Line), cable, fiber optic, dedicated fixed wireless, or other services to access internet service at home. We also asked respondents to measure what percent had access to dial-up internet service (4.2 percent) or satellite internet service (8.5 percent). (See Figures 7 and 8.)

Access to the internet

Study respondents were also largely connected to some type of internet due to the poll limitations of the KnowledgePanel (see notes in Methodology section). While most respondents reported access to high-speed broadband (69.2 percent), 30.8 percent did not. To measure access to home broadband, we asked respondents if they used high-speed broadband internet service, such as DSL (Digital Subscriber Line), cable, fiber optic, dedicated fixed wireless, or other services to access internet service at home. We also asked respondents to measure what percent had access to dial-up internet service (4.2 percent) or satellite internet service (8.5 percent). (See Figures 7 and 8.)

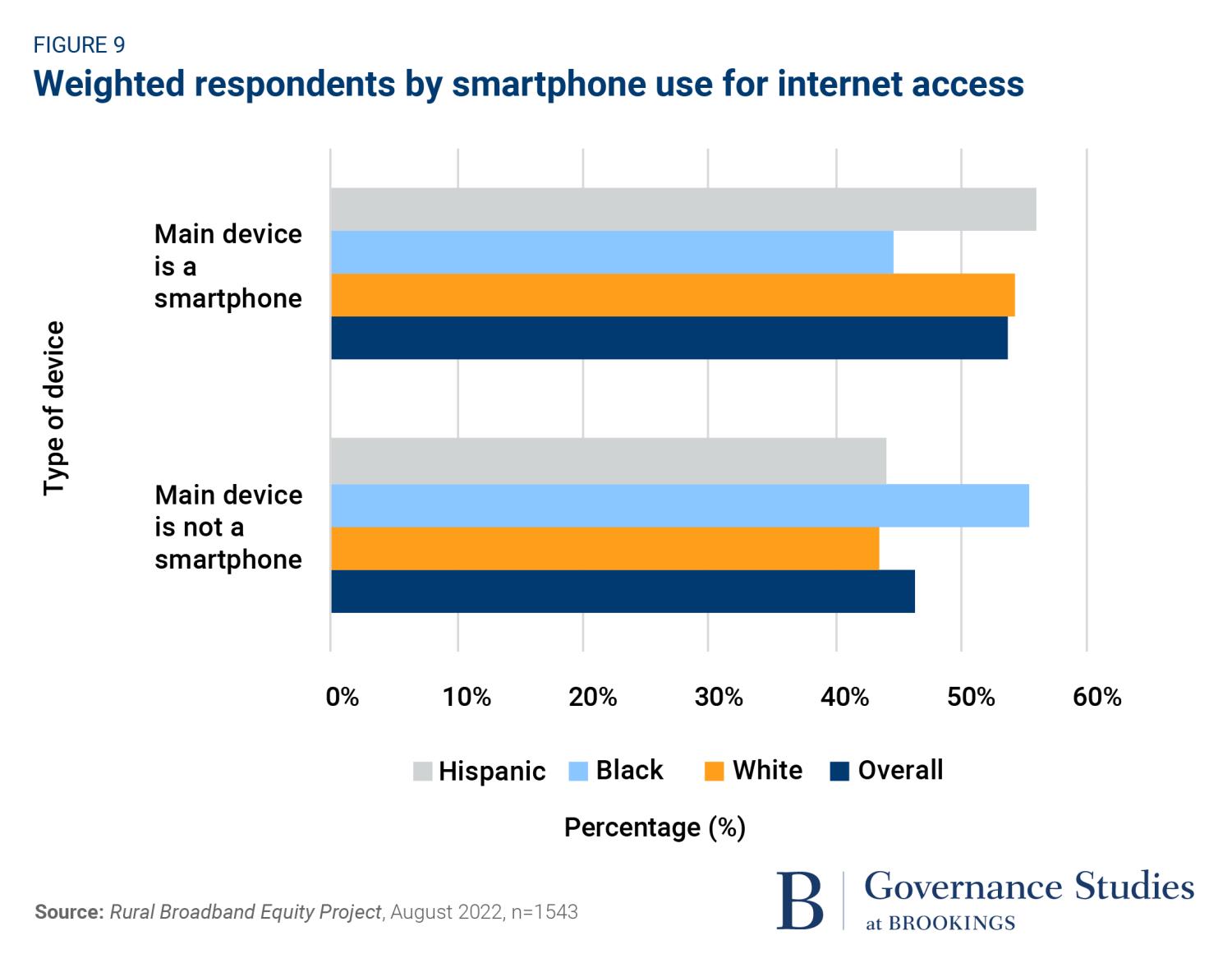

With regards to mobile connectivity, most respondents (53.6 percent) frequently used a smartphone to access the internet, which closely mirrors observed trends of mobile dependency for low-income households. Findings from Pew Research found that the less affluent are more likely to use smartphones to apply for jobs or complete schoolwork. As of early 2021, for adults in households earning less than $30,000 a year, 27 percent are smartphone-dependent internet users.35 Figure 9 presents findings related to smartphone use.

Access to the internet

Study respondents were also largely connected to some type of internet due to the poll limitations of the KnowledgePanel (see notes in Methodology section). While most respondents reported access to high-speed broadband (69.2 percent), 30.8 percent did not. To measure access to home broadband, we asked respondents if they used high-speed broadband internet service, such as DSL (Digital Subscriber Line), cable, fiber optic, dedicated fixed wireless, or other services to access internet service at home. We also asked respondents to measure what percent had access to dial-up internet service (4.2 percent) or satellite internet service (8.5 percent). (See Figures 7 and 8.)

With regards to mobile connectivity, most respondents (53.6 percent) frequently used a smartphone to access the internet, which closely mirrors observed trends of mobile dependency for low-income households. Findings from Pew Research found that the less affluent are more likely to use smartphones to apply for jobs or complete schoolwork. As of early 2021, for adults in households earning less than $30,000 a year, 27 percent are smartphone-dependent internet users.36 Figure 9 presents findings related to smartphone use.

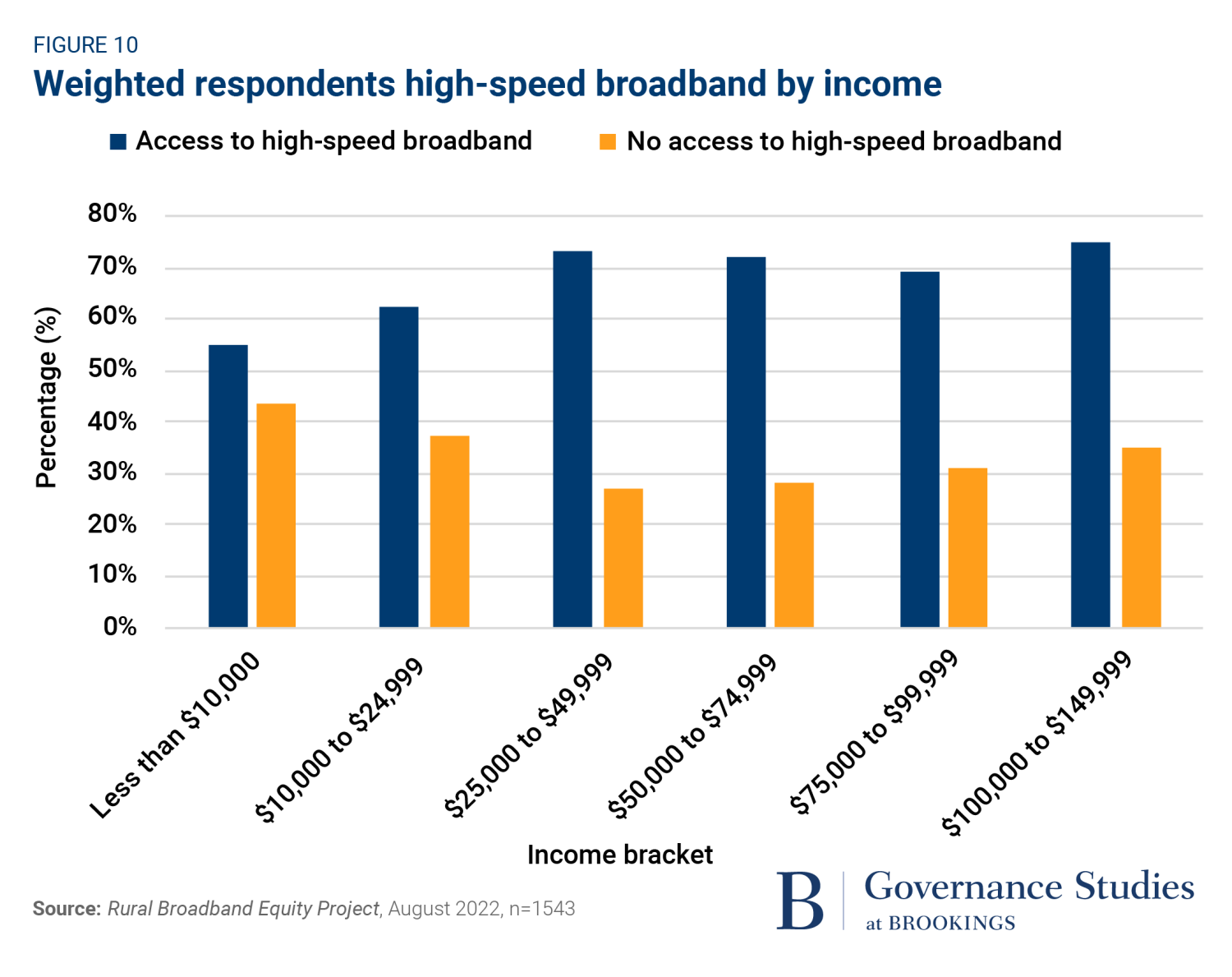

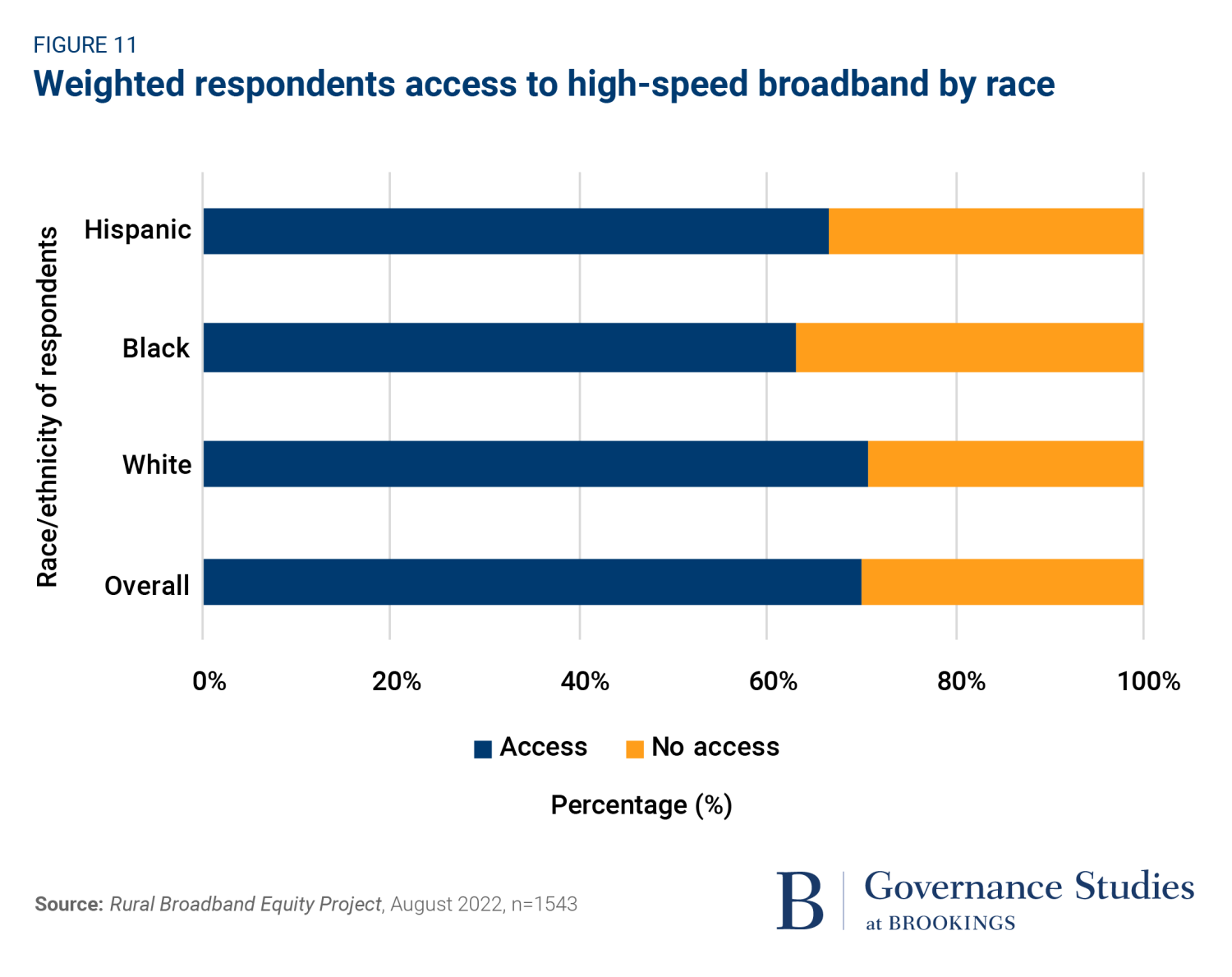

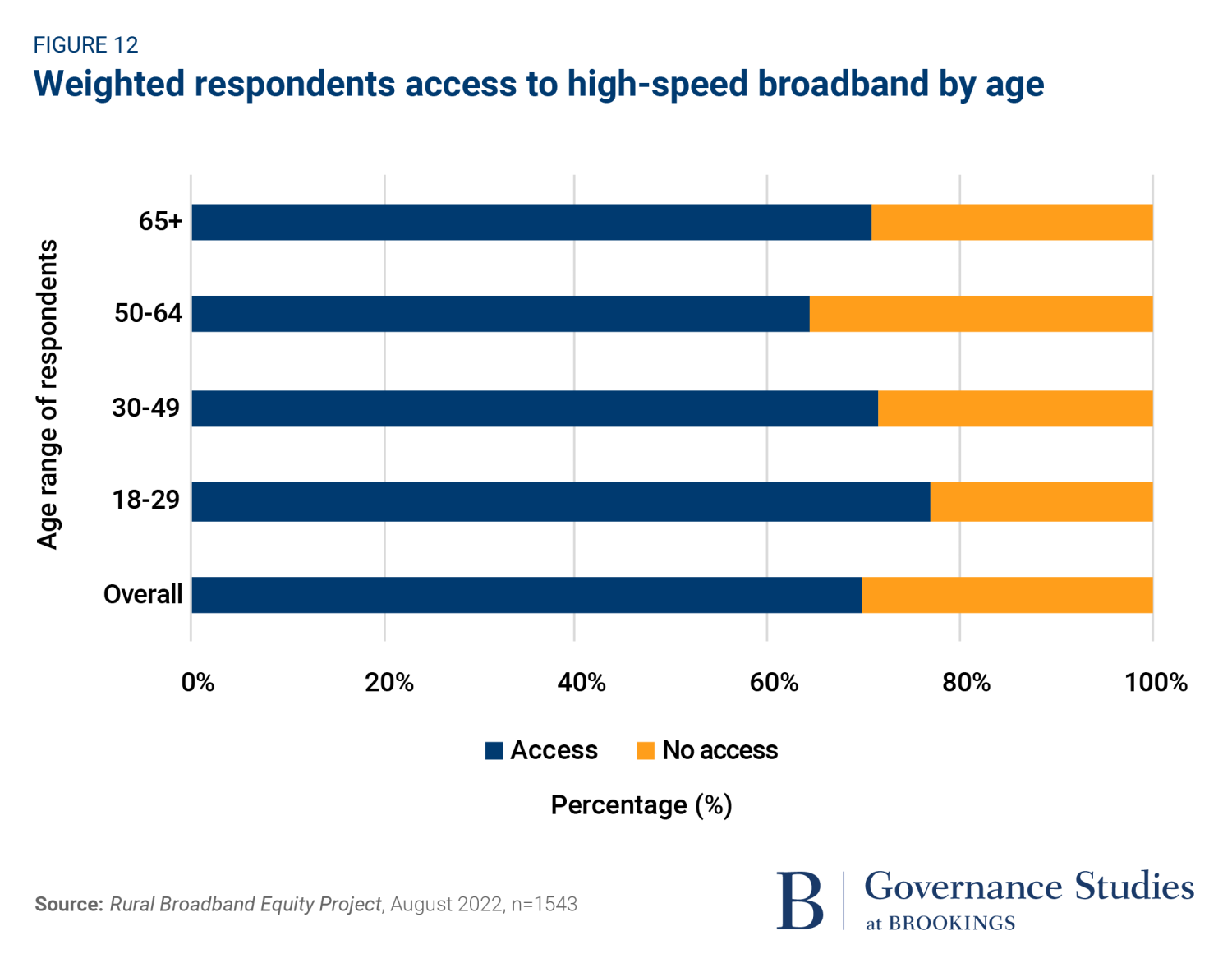

Income and race also tended to affect access to broadband for rural respondents (Figures 10 and 11). The median age for broadband access among the sample was also 18 to 29, with those under 50 having significantly less access to high-speed broadband (Figure 12).

Access to the internet

Study respondents were also largely connected to some type of internet due to the poll limitations of the KnowledgePanel (see notes in Methodology section). While most respondents reported access to high-speed broadband (69.2 percent), 30.8 percent did not. To measure access to home broadband, we asked respondents if they used high-speed broadband internet service, such as DSL (Digital Subscriber Line), cable, fiber optic, dedicated fixed wireless, or other services to access internet service at home. We also asked respondents to measure what percent had access to dial-up internet service (4.2 percent) or satellite internet service (8.5 percent). (See Figures 7 and 8.)

With regards to mobile connectivity, most respondents (53.6 percent) frequently used a smartphone to access the internet, which closely mirrors observed trends of mobile dependency for low-income households. Findings from Pew Research found that the less affluent are more likely to use smartphones to apply for jobs or complete schoolwork. As of early 2021, for adults in households earning less than $30,000 a year, 27 percent are smartphone-dependent internet users.37 Figure 9 presents findings related to smartphone use.

Income and race also tended to affect access to broadband for rural respondents (Figures 10 and 11). The median age for broadband access among the sample was also 18 to 29, with those under 50 having significantly less access to high-speed broadband (Figure 12).

Access to the internet

Study respondents were also largely connected to some type of internet due to the poll limitations of the KnowledgePanel (see notes in Methodology section). While most respondents reported access to high-speed broadband (69.2 percent), 30.8 percent did not. To measure access to home broadband, we asked respondents if they used high-speed broadband internet service, such as DSL (Digital Subscriber Line), cable, fiber optic, dedicated fixed wireless, or other services to access internet service at home. We also asked respondents to measure what percent had access to dial-up internet service (4.2 percent) or satellite internet service (8.5 percent). (See Figures 7 and 8.)

With regards to mobile connectivity, most respondents (53.6 percent) frequently used a smartphone to access the internet, which closely mirrors observed trends of mobile dependency for low-income households. Findings from Pew Research found that the less affluent are more likely to use smartphones to apply for jobs or complete schoolwork. As of early 2021, for adults in households earning less than $30,000 a year, 27 percent are smartphone-dependent internet users.38 Figure 9 presents findings related to smartphone use.

Income and race also tended to affect access to broadband for rural respondents (Figures 10 and 11). The median age for broadband access among the sample was also 18 to 29, with those under 50 having significantly less access to high-speed broadband (Figure 12).

Access to the internet

Study respondents were also largely connected to some type of internet due to the poll limitations of the KnowledgePanel (see notes in Methodology section). While most respondents reported access to high-speed broadband (69.2 percent), 30.8 percent did not. To measure access to home broadband, we asked respondents if they used high-speed broadband internet service, such as DSL (Digital Subscriber Line), cable, fiber optic, dedicated fixed wireless, or other services to access internet service at home. We also asked respondents to measure what percent had access to dial-up internet service (4.2 percent) or satellite internet service (8.5 percent). (See Figures 7 and 8.)

With regards to mobile connectivity, most respondents (53.6 percent) frequently used a smartphone to access the internet, which closely mirrors observed trends of mobile dependency for low-income households. Findings from Pew Research found that the less affluent are more likely to use smartphones to apply for jobs or complete schoolwork. As of early 2021, for adults in households earning less than $30,000 a year, 27 percent are smartphone-dependent internet users.39 Figure 9 presents findings related to smartphone use.

Income and race also tended to affect access to broadband for rural respondents (Figures 10 and 11). The median age for broadband access among the sample was also 18 to 29, with those under 50 having significantly less access to high-speed broadband (Figure 12).

General findings from sample

Among our sample of rural respondents, Black and Hispanic participants were more likely to use a dial-up service to access the internet, at 12.5 percent and 12.2 percent respectively, compared to 3.7 percent of white respondents. Additionally, Black and Hispanic participants are more likely to use satellite, at 17.1 percent and 18.9 percent respectively, compared to 12.3 percent of white respondents. High-speed broadband access greatly depended on income: 54.7 percent of people with an annual income of less than $10,000 have access to high-speed broadband at home, but 74.9 percent of people with an annual income of $100,000 to $149,999 used high-speed broadband at home.

While 53.7 percent of overall respondents use a smartphone most frequently to access the internet, 66.5 percent of respondents aged 30 to 49 use a smartphone most frequently, compared to only 36.6 percent of people aged 65 or older. The percentage of Black respondents who predominantly used a smartphone is also lower, totaling only 44.6 percent. There was no strong correlation of income with smartphone use.

Over the years, minimal attempts to recalibrate the historic funding mechanisms for rural broadband development have been made, which have unfortunately failed to render greater impact for millions of Americans.

Why funding for rural broadband development matters

Research has argued that broadband expansion increases income, lowers unemployment rates,40 creates jobs,41 and makes communities healthier.42 President Biden has also asserted that “[b]roadband is infrastructure.”43 But prior to Biden, other administrations have also positioned access to high-speed broadband as crucial to improved quality of life for everyday residents. The primary difference between Biden and his predecessors is that federal and state governments have exercised limited agency over the facilitation and investment of broadband networks.44 Over the years, minimal attempts to recalibrate the historic funding mechanisms for rural broadband development have been made, which have unfortunately failed to render greater impact for millions of Americans.

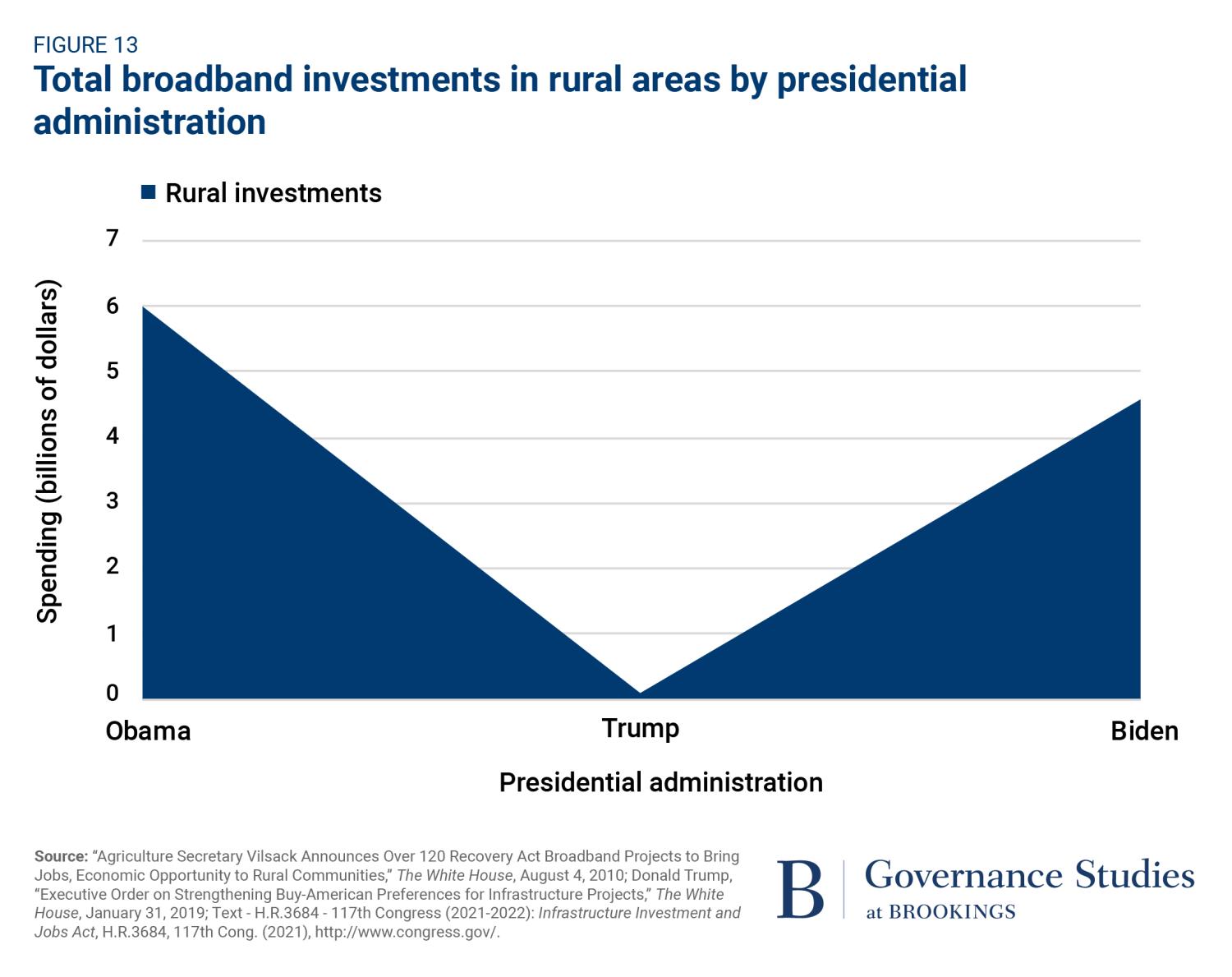

For example, former President Obama’s $7.2 billion investment into the Recovery Act prioritized rural residents and Native American tribal areas in the second round of funding.45 The Trump administration’s executive order reduced barriers for ISPs that wanted to service rural areas.46 Figure 13 illustrates the rural funding trajectories of the Obama, Trump, and Biden administrations.

Access to the internet

Study respondents were also largely connected to some type of internet due to the poll limitations of the KnowledgePanel (see notes in Methodology section). While most respondents reported access to high-speed broadband (69.2 percent), 30.8 percent did not. To measure access to home broadband, we asked respondents if they used high-speed broadband internet service, such as DSL (Digital Subscriber Line), cable, fiber optic, dedicated fixed wireless, or other services to access internet service at home. We also asked respondents to measure what percent had access to dial-up internet service (4.2 percent) or satellite internet service (8.5 percent). (See Figures 7 and 8.)

With regards to mobile connectivity, most respondents (53.6 percent) frequently used a smartphone to access the internet, which closely mirrors observed trends of mobile dependency for low-income households. Findings from Pew Research found that the less affluent are more likely to use smartphones to apply for jobs or complete schoolwork. As of early 2021, for adults in households earning less than $30,000 a year, 27 percent are smartphone-dependent internet users.47 Figure 9 presents findings related to smartphone use.

Income and race also tended to affect access to broadband for rural respondents (Figures 10 and 11). The median age for broadband access among the sample was also 18 to 29, with those under 50 having significantly less access to high-speed broadband (Figure 12).

General findings from sample

Among our sample of rural respondents, Black and Hispanic participants were more likely to use a dial-up service to access the internet, at 12.5 percent and 12.2 percent respectively, compared to 3.7 percent of white respondents. Additionally, Black and Hispanic participants are more likely to use satellite, at 17.1 percent and 18.9 percent respectively, compared to 12.3 percent of white respondents. High-speed broadband access greatly depended on income: 54.7 percent of people with an annual income of less than $10,000 have access to high-speed broadband at home, but 74.9 percent of people with an annual income of $100,000 to $149,999 used high-speed broadband at home.

While 53.7 percent of overall respondents use a smartphone most frequently to access the internet, 66.5 percent of respondents aged 30 to 49 use a smartphone most frequently, compared to only 36.6 percent of people aged 65 or older. The percentage of Black respondents who predominantly used a smartphone is also lower, totaling only 44.6 percent. There was no strong correlation of income with smartphone use.

Over the years, minimal attempts to recalibrate the historic funding mechanisms for rural broadband development have been made, which have unfortunately failed to render greater impact for millions of Americans.

Why funding for rural broadband development matters

Research has argued that broadband expansion increases income, lowers unemployment rates,48 creates jobs,49 and makes communities healthier.50 President Biden has also asserted that “[b]roadband is infrastructure.”51 But prior to Biden, other administrations have also positioned access to high-speed broadband as crucial to improved quality of life for everyday residents. The primary difference between Biden and his predecessors is that federal and state governments have exercised limited agency over the facilitation and investment of broadband networks.52 Over the years, minimal attempts to recalibrate the historic funding mechanisms for rural broadband development have been made, which have unfortunately failed to render greater impact for millions of Americans.

For example, former President Obama’s $7.2 billion investment into the Recovery Act prioritized rural residents and Native American tribal areas in the second round of funding.53 The Trump administration’s executive order reduced barriers for ISPs that wanted to service rural areas.54 Figure 13 illustrates the rural funding trajectories of the Obama, Trump, and Biden administrations.

But despite these and prior efforts, the U.S. has still lagged in their efforts to close the divides impacting rural and urban communities, which can hopefully change course with IIJA investments. Rural communities are still largely left behind in broadband deployment as ISPs find local infrastructure investments less profitable. As even the FCC has stated, rural areas have less access to broadband infrastructure than urban areas, and rural areas have fallen behind urban and suburban levels of fixed broadband by 54 percent.55 Only 19 percent of rural Americans have more than one broadband option.56 And the lack of competition can lead to high prices, which explains why low-density population areas pay on average 37 percent more than urban areas.57

Even when federal legislation is used to try to address the issue, like legislation stewarded by the Rural Utilities Service (RUS), agencies have not been held accountable for the limited progress in rural broadband development until now. RUS is responsible for building out infrastructure in rural communities, which includes, but is not limited to, broadband deployment through its telecommunications programs which provide loans and grants for eligible entities.58 But the agency has experienced some challenges in distributing support. In 2009, it was found that RUS invested in more affluent neighborhoods in Texas.59 In 2015, some borrowers defaulted on their loans or did not withdraw funds, while some funds went to areas with existing high-speed broadband.60 These and other examples suggest a necessary overhaul in management and reporting of existing and future rural broadband investments. The Connect America Fund (CAF), created by the Obama administration, provided generous funding for ISPs to build out into rural areas, yet some failed to complete projects and meet deadlines.61 Even funding allocated specifically for rural communities, such as the Rural Digital Opportunity Fund (RDOF), managed by the Universal Service Administrative Company (USAC) with oversight from the FCC, gave funding to companies claiming to service areas where they were unable to build broadband.62

- Despite these challenges, other federal funding mechanisms have been more successful in further facilitating rural broadband development, including the ReConnect Loan and Grant Program and earmarked resources for the Tribal Broadband Connectivity Grant. Both programs are described below.

- ReConnect Loan and Grant Program – The U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) Rural Development oversees the ReConnect Loan and Grant Program, which provides funds for the costs of construction, improvement, or acquisition of facilities and equipment needed to provide broadband service to rural areas without sufficient broadband access.63 On November 24, 2021, the USDA announced it had begun accepting applications for up to $1.15 billion in loans and grants.64 In order to qualify, areas must be rural and without sufficient access to broadband service.65 Currently, the USDA is preparing for a fourth round of funding proposals to add to a total of $1,862,364,505 invested through the ReConnect Program over the last three rounds.66 Under the Biden administration, the barriers to application have been minimized, and some of the stipulations waived to allow for more robust participation by small and large providers.

- Tribal Broadband Connectivity Grant – Even though we do not discuss tribal lands extensively in this paper, it is worth noting that the NTIA oversees the Tribal Broadband Connectivity Grant Program, which allocates $1 billion in annual funding for broadband deployment on tribal lands. Tribal governments, TCUs, and Native corporations are eligible to apply for a grant, and, in addition to broadband deployment, these funds can also be used for digital literacy programs, distance education, and telehealth.67 Most recent grant awards as of August 2022 include nearly $50 million in grants to expand internet access on tribal lands in Mississippi and Oklahoma, in addition to an over $146 million investment in tribal lands in New Mexico. So far, the NTIA has issued 53 awards totaling more than $339 million through the program.68

- Rural Health Care Program – Another program overseen by the FCC, the Rural Health Care Program, provides funding to eligible health care providers for telecommunications and broadband services required for health care. Non-profit and public health care providers are eligible for this funding, which aims to improve the quality of health care available for rural patients. Funding for the program is capped at $571 million annually with adjustments for inflation.69 The program is made up of two separate programs. First, the Healthcare Connect Fund Program, created in 2012, provides connectivity support for health care providers. Meanwhile, the Telecommunications Program, created in 1997, subsidizes the difference between urban and rural rates for telecommunications services.70

- Connecting Minority Communities Pilot Program – The NTIA is also in charge of the Connecting Minority Communities Pilot Program, a $268 million grant program for Historically Black Colleges and Universities (HBCUs), Tribal Colleges and Universities (TCUs), and Minority-Serving Institutions (MSIs) to assist them with the purchase of broadband internet access service and eligible equipment or to hire and train information technology personnel. The NTIA has allocated more than $10 million in grants for this program.71

These and other programs have been operational prior to the enactment of the IIJA, whose programs are described in the next section.

The IIJA

Implicitly, the IIJA should complement these existing programs, while addressing the challenges of universal broadband and the digital divide slightly differently. Under the new federal law, states and localities will be responsible for distributing the resources and conducting oversight to ensure that the expended funds are used to meet the stated goals of the IIJA programs, including, inter alia, closing the digital divide, preventing digital discrimination, and expanding broadband access in marginalized communities. IIJA support is shared among various programs, which are as follows:

The Broadband Equity, Access, and Deployment Program (BEAD)

The Broadband Equity, Access, and Deployment Program (BEAD) provides $42.45 billion in grant funding overseen by the NTIA for the planning, deployment, mapping, and adoption of broadband. The BEAD Program prioritizes unserved areas, underserved areas, and anchor institutions. Unserved locations are “broadband-serviceable locations” without broadband service “at speeds of at least 25 Mbps downstream and 3 Mbps upstream and latency levels low enough to support real-time, interactive applications”.72 Underserved locations lack access to broadband service at speeds of 100 Mbps downstream and 20 Mbps upstream.73 The IIJA defines community anchor institutions as “any nonprofit or governmental community support organization,” such as libraries, healthcare providers, or public schools.74

As part of the application process, states must submit a Five-Year Action Plan detailing how broadband expansion will align with digital equity, workforce development, and other objectives. The plan must be developed collaboratively with state, local, tribal entities, unions, and other worker organizations.75

In late August 2022, Louisiana became the first state to receive $3 million in funding to expand broadband access through the IIJA after applying to the BEAD program.76 The grant consists of $2 million for planning, and $941,542.28 in Digital Equity Act funding to enable the creation of a statewide digital equity plan or to find some way to engage with the National Digital Inclusion Alliance.77 The portion of rural allocations in the grant is currently unclear, but at a Broadband Solutions Summit, Louisiana Senator Bill Cassidy spoke to how this funding will help expand rural broadband access across Louisiana.78

The Enabling Middle Mile Broadband Instructure Program

The Enabling Middle Mile Broadband Infrastructure Program, which provides $1 billion in grant funding overseen by the NTIA for deployment, construction, improvement, or acquisition of middle mile infrastructure, requires that programs either identify “specific, documented and sustainable demand for middle mile interconnect,” or “demonstrate benefits to national security interests.”

State digital equity programs

Lastly, the State Digital Equity Capacity Grant Program and Digital Equity Competitive Grant Program collectively will provide $2.69 billion for unserved, underserved, and, lastly, community anchor institutions, focusing on covered households and covered populations.79 “Covered households” is used by the U.S. Census Bureau to measure poverty if a household’s income is no more than 150 percent of the completed year’s poverty level. “Covered individuals” is a far larger group that refers to individuals who live in covered households, as well as aging individuals, incarcerated individuals, veterans, individuals with disabilities, individuals with a language barrier, individuals who are members of a racial or ethnic minority group, or individuals who primarily reside in a rural area.80

Put simply, the combined IIJA allotments, along with the simultaneous distribution of funds from the U.S. Treasury and other federally mandated programs, should secure livable broadband futures and more robust digital lives for rural residents.

The legislation also includes support for the pioneering affordability program – the Affordable Connectivity Program (ACP) – that offers $14 billion to the FCC for monthly discounts to the broadband bills of eligible low-income consumers. While not initially created by the IIJA, the ACP received additional funding from the legislative directive, adding on to the existing $3.2 billion allocated from the Consolidated Appropriations Act in 2021. If a household already meets the requirements of an internet service provider’s existing low-income program; qualifies for Lifeline benefits; participates in a tribal assistance program; has a member who is a Pell Grant recipient;, benefits through the free and reduced school lunch program; or has an income at or below 200 percent of the federal poverty guidelines, they can apply for ACP benefits which provide a $30 discount on service and associated equipment every month ($75 a month for households on tribal lands), as well as a one-time discount on a laptop, tablet, or desktop computer of up to $100 for qualifying low-income households with between $10 and $50 household contribution.81 As of June 6, 2022, there were 12.6 million households enrolled in ACP benefits.82

Moving forward, support from the IIJA should require up-to-date and complete broadband data about community deployment needs and those of individual consumers. The FCC is in the process of completing new national and state maps, which can help States and localities decide how to allocate their funding. In March 2020, Congress passed the Broadband Deployment Accuracy and Technological Availability (DATA) Act, which introduces changes to how the FCC collects, verifies, and reports broadband data.83 These new maps aim to better represent rural communities by giving individuals the opportunity to dispute areas of coverage reported by ISPs. This will ultimately help federal broadband programs better target unserved and underserved locations.

Put simply, the combined IIJA allotments, along with the simultaneous distribution of funds from the U.S. Treasury and other federally mandated programs, should secure livable broadband futures and more robust digital lives for rural residents. Yet, much is still unknown as to whether these efforts will improve the quality of life for the intended subjects. particularly when their needs are largely unarticulated in the public domain.

Who rural Americans believe is responsible for connecting them to broadband internet

The reasons discussed above are why it is important to explore who rural Americans believe are responsible for solving the digital divide they face. As part of this research, we query individual perceptions and/or sentiments around which actors respondents believe to be most responsible for expanding rural broadband access, and who is missing from local digital infrastructure.

To gauge the perceptions of who should be responsible and accountable for ensuring broadband internet within the rural communities surveyed, we asked the following questions:

- In your opinion, which organizations, if any, should be responsible for bringing affordable, high-speed home internet to people who want to get online in the United States?

- In your opinion, who should be responsible for paying the costs for consumers who may not be able to afford high-speed internet in the U.S., including building out more choices in communities?

- Of the organizations you selected, who should mainly be responsible for ensuring affordable and available high-speed internet to your community?

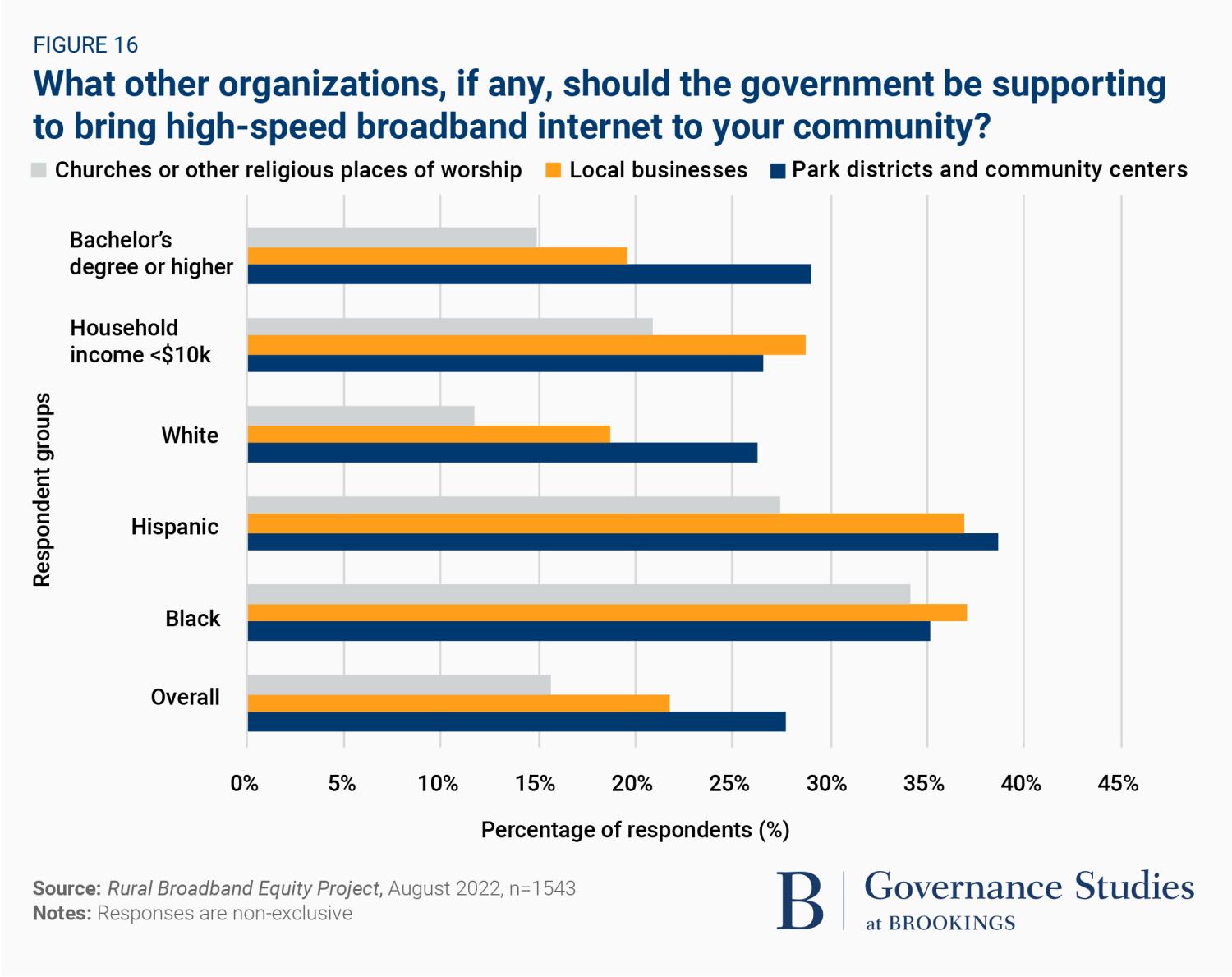

- Currently, the government funds schools and libraries to bring high-speed internet to communities. What other organizations, if any, should the government be supporting to bring high-speed broadband internet to your community?

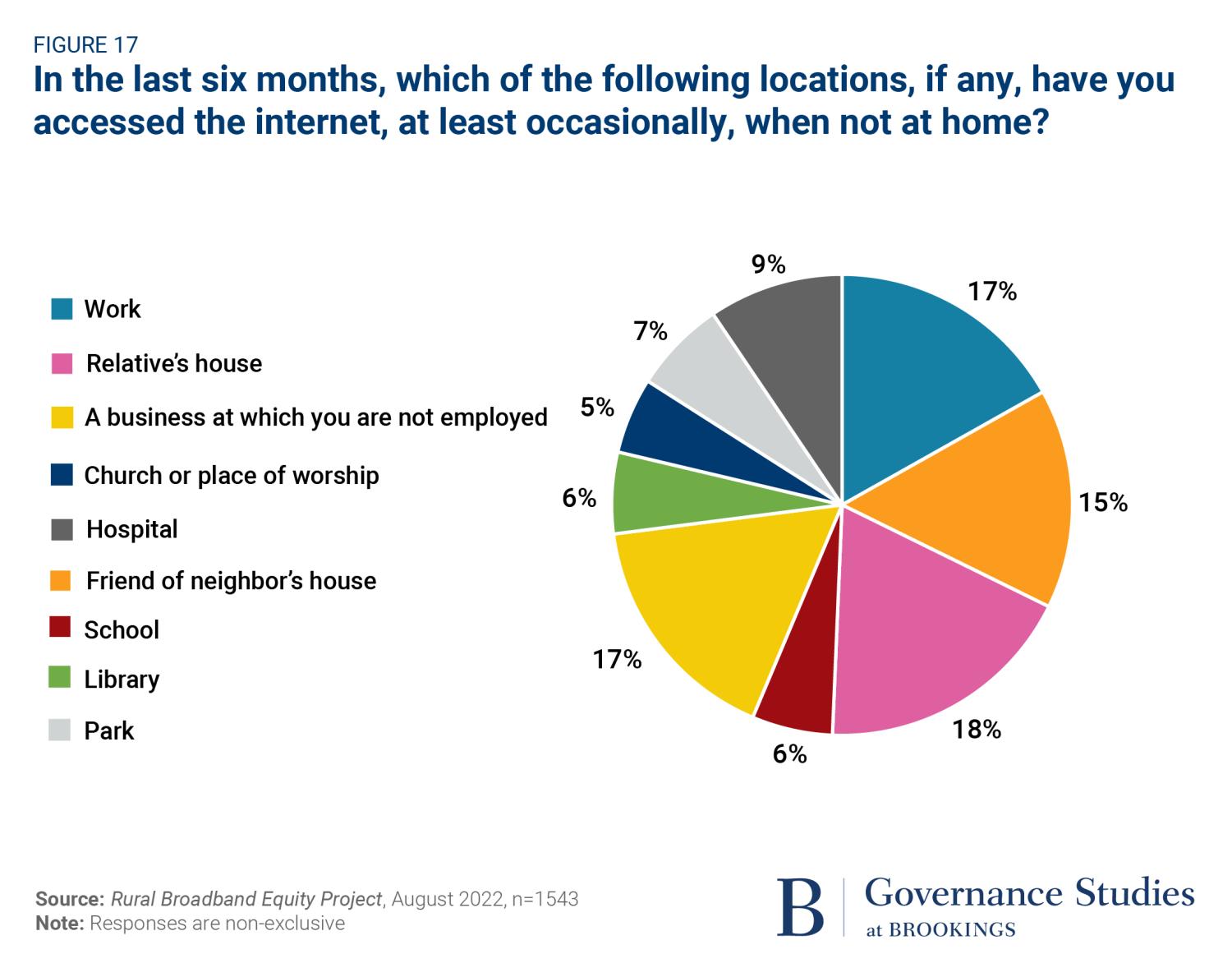

- In the last six months, in which of the following locations, if any, have you accessed the internet, at least occasionally, when not at home?

We considered responses of at least n=150 when determining statistical significance and drawing conclusions, so the sum of n-values in figures may be less than the total sample size. Overall, the measurements of accountability fall along income and racial lines, suggesting that the least unserved and undeserved by high-speed broadband are seeking out government supports to finally be connected.

Findings

Respondents differ on who is responsible for bringing internet access to their communities, and what entity (e.g., federal and state governments, or ISPs) is responsible for paying for it.

Generally, most survey respondents (58.3 percent) believe that ISPs should be responsible for bringing high speed, affordable and available high-speed internet to people who want to get online in the U.S. When respondents were asked to select all entities who they believed were responsible for delivering high-speed internet, 54.6 percent of people said ISPs were responsible, compared to only 33.7 percent who said the federal government was responsible and 30.7 percent who said state governments. Even fewer people responded that local governments and organizations are responsible for bringing internet access to their communities.

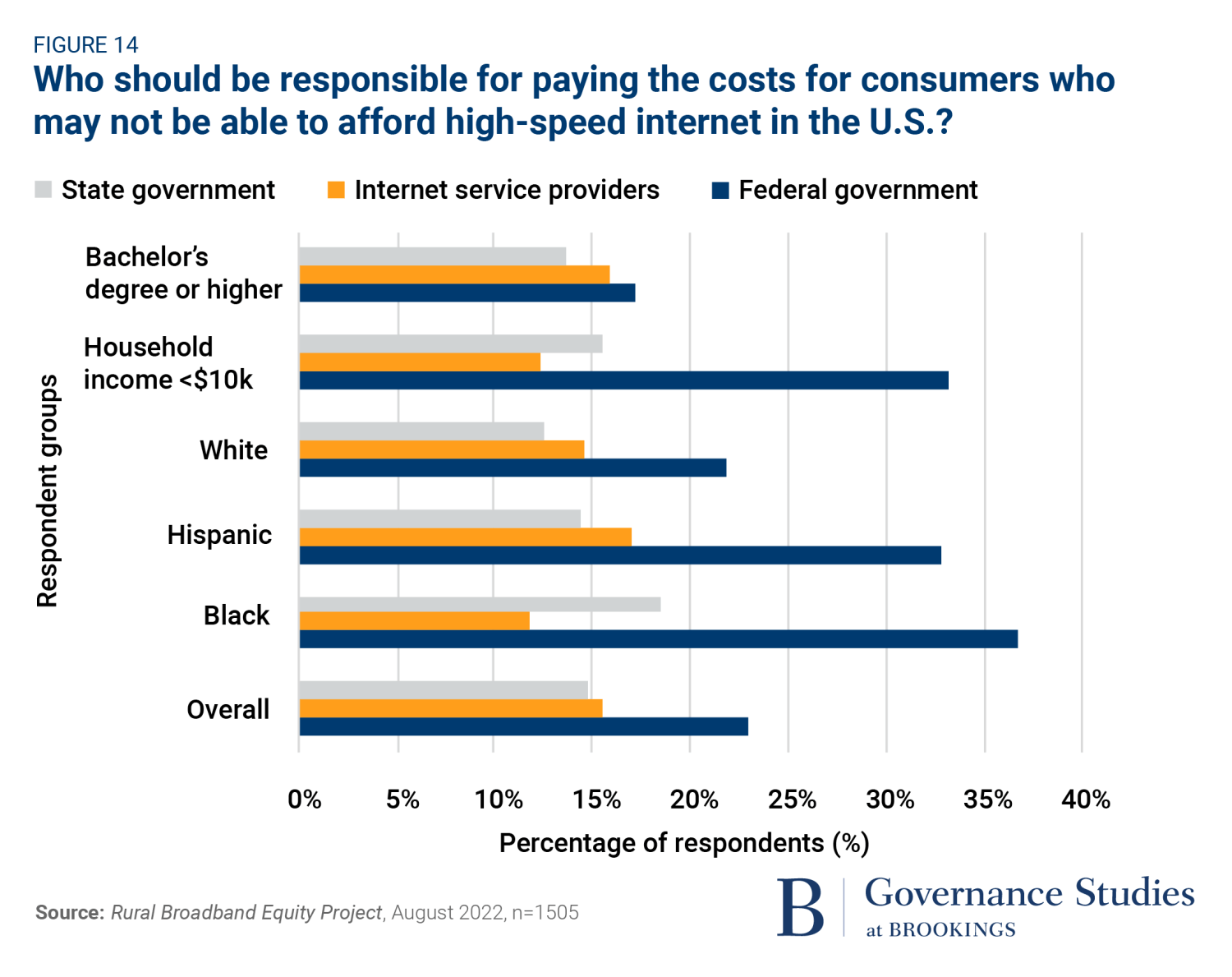

However, when asked who should pay for the costs of consumers who cannot afford high-speed internet, more people (35.1 percent) thought that the federal government should pay, compared to only 22.9 percent who selected ISPs (Figure 14).

Access to the internet

Study respondents were also largely connected to some type of internet due to the poll limitations of the KnowledgePanel (see notes in Methodology section). While most respondents reported access to high-speed broadband (69.2 percent), 30.8 percent did not. To measure access to home broadband, we asked respondents if they used high-speed broadband internet service, such as DSL (Digital Subscriber Line), cable, fiber optic, dedicated fixed wireless, or other services to access internet service at home. We also asked respondents to measure what percent had access to dial-up internet service (4.2 percent) or satellite internet service (8.5 percent). (See Figures 7 and 8.)

With regards to mobile connectivity, most respondents (53.6 percent) frequently used a smartphone to access the internet, which closely mirrors observed trends of mobile dependency for low-income households. Findings from Pew Research found that the less affluent are more likely to use smartphones to apply for jobs or complete schoolwork. As of early 2021, for adults in households earning less than $30,000 a year, 27 percent are smartphone-dependent internet users.84 Figure 9 presents findings related to smartphone use.

Income and race also tended to affect access to broadband for rural respondents (Figures 10 and 11). The median age for broadband access among the sample was also 18 to 29, with those under 50 having significantly less access to high-speed broadband (Figure 12).

General findings from sample

Among our sample of rural respondents, Black and Hispanic participants were more likely to use a dial-up service to access the internet, at 12.5 percent and 12.2 percent respectively, compared to 3.7 percent of white respondents. Additionally, Black and Hispanic participants are more likely to use satellite, at 17.1 percent and 18.9 percent respectively, compared to 12.3 percent of white respondents. High-speed broadband access greatly depended on income: 54.7 percent of people with an annual income of less than $10,000 have access to high-speed broadband at home, but 74.9 percent of people with an annual income of $100,000 to $149,999 used high-speed broadband at home.

While 53.7 percent of overall respondents use a smartphone most frequently to access the internet, 66.5 percent of respondents aged 30 to 49 use a smartphone most frequently, compared to only 36.6 percent of people aged 65 or older. The percentage of Black respondents who predominantly used a smartphone is also lower, totaling only 44.6 percent. There was no strong correlation of income with smartphone use.

Over the years, minimal attempts to recalibrate the historic funding mechanisms for rural broadband development have been made, which have unfortunately failed to render greater impact for millions of Americans.

Why funding for rural broadband development matters

Research has argued that broadband expansion increases income, lowers unemployment rates,85 creates jobs,86 and makes communities healthier.87 President Biden has also asserted that “[b]roadband is infrastructure.”88 But prior to Biden, other administrations have also positioned access to high-speed broadband as crucial to improved quality of life for everyday residents. The primary difference between Biden and his predecessors is that federal and state governments have exercised limited agency over the facilitation and investment of broadband networks.89 Over the years, minimal attempts to recalibrate the historic funding mechanisms for rural broadband development have been made, which have unfortunately failed to render greater impact for millions of Americans.

For example, former President Obama’s $7.2 billion investment into the Recovery Act prioritized rural residents and Native American tribal areas in the second round of funding.90 The Trump administration’s executive order reduced barriers for ISPs that wanted to service rural areas.91 Figure 13 illustrates the rural funding trajectories of the Obama, Trump, and Biden administrations.

But despite these and prior efforts, the U.S. has still lagged in their efforts to close the divides impacting rural and urban communities, which can hopefully change course with IIJA investments. Rural communities are still largely left behind in broadband deployment as ISPs find local infrastructure investments less profitable. As even the FCC has stated, rural areas have less access to broadband infrastructure than urban areas, and rural areas have fallen behind urban and suburban levels of fixed broadband by 54 percent.92 Only 19 percent of rural Americans have more than one broadband option.93 And the lack of competition can lead to high prices, which explains why low-density population areas pay on average 37 percent more than urban areas.94

Even when federal legislation is used to try to address the issue, like legislation stewarded by the Rural Utilities Service (RUS), agencies have not been held accountable for the limited progress in rural broadband development until now. RUS is responsible for building out infrastructure in rural communities, which includes, but is not limited to, broadband deployment through its telecommunications programs which provide loans and grants for eligible entities.95 But the agency has experienced some challenges in distributing support. In 2009, it was found that RUS invested in more affluent neighborhoods in Texas.96 In 2015, some borrowers defaulted on their loans or did not withdraw funds, while some funds went to areas with existing high-speed broadband.97 These and other examples suggest a necessary overhaul in management and reporting of existing and future rural broadband investments. The Connect America Fund (CAF), created by the Obama administration, provided generous funding for ISPs to build out into rural areas, yet some failed to complete projects and meet deadlines.98 Even funding allocated specifically for rural communities, such as the Rural Digital Opportunity Fund (RDOF), managed by the Universal Service Administrative Company (USAC) with oversight from the FCC, gave funding to companies claiming to service areas where they were unable to build broadband.99

- Despite these challenges, other federal funding mechanisms have been more successful in further facilitating rural broadband development, including the ReConnect Loan and Grant Program and earmarked resources for the Tribal Broadband Connectivity Grant. Both programs are described below.

- ReConnect Loan and Grant Program – The U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) Rural Development oversees the ReConnect Loan and Grant Program, which provides funds for the costs of construction, improvement, or acquisition of facilities and equipment needed to provide broadband service to rural areas without sufficient broadband access.100 On November 24, 2021, the USDA announced it had begun accepting applications for up to $1.15 billion in loans and grants.101 In order to qualify, areas must be rural and without sufficient access to broadband service.102 Currently, the USDA is preparing for a fourth round of funding proposals to add to a total of $1,862,364,505 invested through the ReConnect Program over the last three rounds.103 Under the Biden administration, the barriers to application have been minimized, and some of the stipulations waived to allow for more robust participation by small and large providers.

- Tribal Broadband Connectivity Grant – Even though we do not discuss tribal lands extensively in this paper, it is worth noting that the NTIA oversees the Tribal Broadband Connectivity Grant Program, which allocates $1 billion in annual funding for broadband deployment on tribal lands. Tribal governments, TCUs, and Native corporations are eligible to apply for a grant, and, in addition to broadband deployment, these funds can also be used for digital literacy programs, distance education, and telehealth.104 Most recent grant awards as of August 2022 include nearly $50 million in grants to expand internet access on tribal lands in Mississippi and Oklahoma, in addition to an over $146 million investment in tribal lands in New Mexico. So far, the NTIA has issued 53 awards totaling more than $339 million through the program.105

- Rural Health Care Program – Another program overseen by the FCC, the Rural Health Care Program, provides funding to eligible health care providers for telecommunications and broadband services required for health care. Non-profit and public health care providers are eligible for this funding, which aims to improve the quality of health care available for rural patients. Funding for the program is capped at $571 million annually with adjustments for inflation.106 The program is made up of two separate programs. First, the Healthcare Connect Fund Program, created in 2012, provides connectivity support for health care providers. Meanwhile, the Telecommunications Program, created in 1997, subsidizes the difference between urban and rural rates for telecommunications services.107

- Connecting Minority Communities Pilot Program – The NTIA is also in charge of the Connecting Minority Communities Pilot Program, a $268 million grant program for Historically Black Colleges and Universities (HBCUs), Tribal Colleges and Universities (TCUs), and Minority-Serving Institutions (MSIs) to assist them with the purchase of broadband internet access service and eligible equipment or to hire and train information technology personnel. The NTIA has allocated more than $10 million in grants for this program.108

These and other programs have been operational prior to the enactment of the IIJA, whose programs are described in the next section.

The IIJA

Implicitly, the IIJA should complement these existing programs, while addressing the challenges of universal broadband and the digital divide slightly differently. Under the new federal law, states and localities will be responsible for distributing the resources and conducting oversight to ensure that the expended funds are used to meet the stated goals of the IIJA programs, including, inter alia, closing the digital divide, preventing digital discrimination, and expanding broadband access in marginalized communities. IIJA support is shared among various programs, which are as follows:

The Broadband Equity, Access, and Deployment Program (BEAD)

The Broadband Equity, Access, and Deployment Program (BEAD) provides $42.45 billion in grant funding overseen by the NTIA for the planning, deployment, mapping, and adoption of broadband. The BEAD Program prioritizes unserved areas, underserved areas, and anchor institutions. Unserved locations are “broadband-serviceable locations” without broadband service “at speeds of at least 25 Mbps downstream and 3 Mbps upstream and latency levels low enough to support real-time, interactive applications”.109 Underserved locations lack access to broadband service at speeds of 100 Mbps downstream and 20 Mbps upstream.110 The IIJA defines community anchor institutions as “any nonprofit or governmental community support organization,” such as libraries, healthcare providers, or public schools.111

As part of the application process, states must submit a Five-Year Action Plan detailing how broadband expansion will align with digital equity, workforce development, and other objectives. The plan must be developed collaboratively with state, local, tribal entities, unions, and other worker organizations.112

In late August 2022, Louisiana became the first state to receive $3 million in funding to expand broadband access through the IIJA after applying to the BEAD program.113 The grant consists of $2 million for planning, and $941,542.28 in Digital Equity Act funding to enable the creation of a statewide digital equity plan or to find some way to engage with the National Digital Inclusion Alliance.114 The portion of rural allocations in the grant is currently unclear, but at a Broadband Solutions Summit, Louisiana Senator Bill Cassidy spoke to how this funding will help expand rural broadband access across Louisiana.115

The Enabling Middle Mile Broadband Instructure Program

The Enabling Middle Mile Broadband Infrastructure Program, which provides $1 billion in grant funding overseen by the NTIA for deployment, construction, improvement, or acquisition of middle mile infrastructure, requires that programs either identify “specific, documented and sustainable demand for middle mile interconnect,” or “demonstrate benefits to national security interests.”

State digital equity programs

Lastly, the State Digital Equity Capacity Grant Program and Digital Equity Competitive Grant Program collectively will provide $2.69 billion for unserved, underserved, and, lastly, community anchor institutions, focusing on covered households and covered populations.116 “Covered households” is used by the U.S. Census Bureau to measure poverty if a household’s income is no more than 150 percent of the completed year’s poverty level. “Covered individuals” is a far larger group that refers to individuals who live in covered households, as well as aging individuals, incarcerated individuals, veterans, individuals with disabilities, individuals with a language barrier, individuals who are members of a racial or ethnic minority group, or individuals who primarily reside in a rural area.117

Put simply, the combined IIJA allotments, along with the simultaneous distribution of funds from the U.S. Treasury and other federally mandated programs, should secure livable broadband futures and more robust digital lives for rural residents.

The legislation also includes support for the pioneering affordability program – the Affordable Connectivity Program (ACP) – that offers $14 billion to the FCC for monthly discounts to the broadband bills of eligible low-income consumers. While not initially created by the IIJA, the ACP received additional funding from the legislative directive, adding on to the existing $3.2 billion allocated from the Consolidated Appropriations Act in 2021. If a household already meets the requirements of an internet service provider’s existing low-income program; qualifies for Lifeline benefits; participates in a tribal assistance program; has a member who is a Pell Grant recipient;, benefits through the free and reduced school lunch program; or has an income at or below 200 percent of the federal poverty guidelines, they can apply for ACP benefits which provide a $30 discount on service and associated equipment every month ($75 a month for households on tribal lands), as well as a one-time discount on a laptop, tablet, or desktop computer of up to $100 for qualifying low-income households with between $10 and $50 household contribution.118 As of June 6, 2022, there were 12.6 million households enrolled in ACP benefits.119

Moving forward, support from the IIJA should require up-to-date and complete broadband data about community deployment needs and those of individual consumers. The FCC is in the process of completing new national and state maps, which can help States and localities decide how to allocate their funding. In March 2020, Congress passed the Broadband Deployment Accuracy and Technological Availability (DATA) Act, which introduces changes to how the FCC collects, verifies, and reports broadband data.120 These new maps aim to better represent rural communities by giving individuals the opportunity to dispute areas of coverage reported by ISPs. This will ultimately help federal broadband programs better target unserved and underserved locations.

Put simply, the combined IIJA allotments, along with the simultaneous distribution of funds from the U.S. Treasury and other federally mandated programs, should secure livable broadband futures and more robust digital lives for rural residents. Yet, much is still unknown as to whether these efforts will improve the quality of life for the intended subjects. particularly when their needs are largely unarticulated in the public domain.

Who rural Americans believe is responsible for connecting them to broadband internet

The reasons discussed above are why it is important to explore who rural Americans believe are responsible for solving the digital divide they face. As part of this research, we query individual perceptions and/or sentiments around which actors respondents believe to be most responsible for expanding rural broadband access, and who is missing from local digital infrastructure.

To gauge the perceptions of who should be responsible and accountable for ensuring broadband internet within the rural communities surveyed, we asked the following questions:

- In your opinion, which organizations, if any, should be responsible for bringing affordable, high-speed home internet to people who want to get online in the United States?

- In your opinion, who should be responsible for paying the costs for consumers who may not be able to afford high-speed internet in the U.S., including building out more choices in communities?

- Of the organizations you selected, who should mainly be responsible for ensuring affordable and available high-speed internet to your community?

- Currently, the government funds schools and libraries to bring high-speed internet to communities. What other organizations, if any, should the government be supporting to bring high-speed broadband internet to your community?

- In the last six months, in which of the following locations, if any, have you accessed the internet, at least occasionally, when not at home?

We considered responses of at least n=150 when determining statistical significance and drawing conclusions, so the sum of n-values in figures may be less than the total sample size. Overall, the measurements of accountability fall along income and racial lines, suggesting that the least unserved and undeserved by high-speed broadband are seeking out government supports to finally be connected.

Findings

Respondents differ on who is responsible for bringing internet access to their communities, and what entity (e.g., federal and state governments, or ISPs) is responsible for paying for it.

Generally, most survey respondents (58.3 percent) believe that ISPs should be responsible for bringing high speed, affordable and available high-speed internet to people who want to get online in the U.S. When respondents were asked to select all entities who they believed were responsible for delivering high-speed internet, 54.6 percent of people said ISPs were responsible, compared to only 33.7 percent who said the federal government was responsible and 30.7 percent who said state governments. Even fewer people responded that local governments and organizations are responsible for bringing internet access to their communities.

However, when asked who should pay for the costs of consumers who cannot afford high-speed internet, more people (35.1 percent) thought that the federal government should pay, compared to only 22.9 percent who selected ISPs (Figure 14).

Respondents also differ on whether the government should be held responsible for broadband deployment. People with a higher education were less likely to hold the federal government responsible: only 14.2 percent of people with a bachelor’s degree or higher education thought that the federal government should be responsible for increasing access to high-speed internet, compared to 22 percent of all survey respondents. However, people with household incomes under $10,000 annually—who were more likely to be on government assistance or enrolled in the ACP by 8.1 percentage points—were more likely to agree that federal and state governments should bear more responsibility than the overall population. In fact, 49.1 percent of the population of low-income households said that the federal government should be responsible for high-speed internet access deployment, compared to 33.3 percent overall.

Differences in race and ethnicity drive stronger accountability from the federal government.

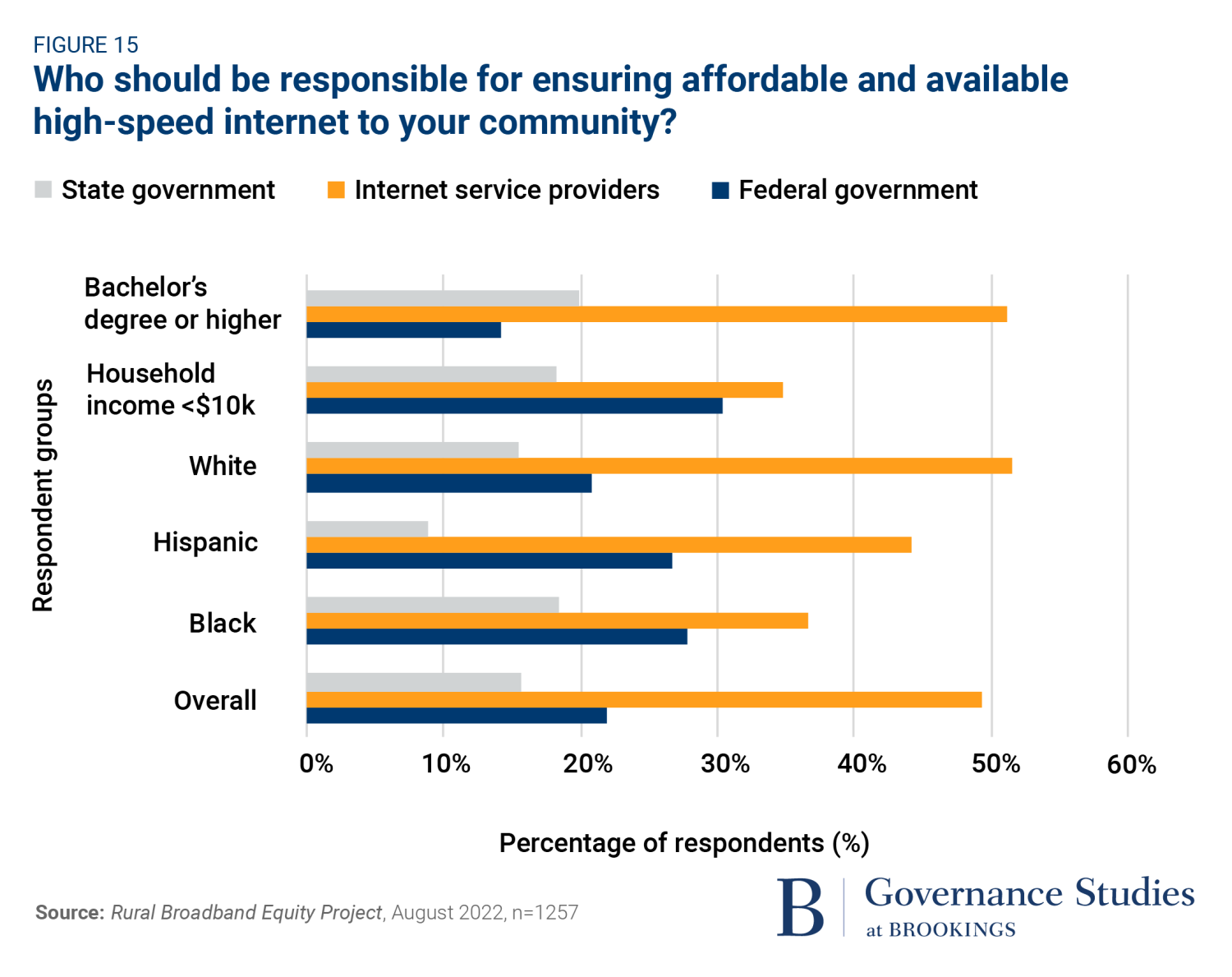

Conversely, only 36.7 percent of Black respondents and 44.1 percent of Hispanic respondents thought that ISPs should be responsible for bringing affordable internet to their communities, compared to 49.4 percent overall – suggesting greater accountability for the federal government to address digital inequities. While these numbers could be skewed based on respondents’ awareness of the role of ISPs in broadband deployment, like lower–income respondents, Black and Hispanic participants were more likely to hold the federal government solely accountable. While 20 percent of all study respondents overall thought the federal government was entirely responsible for expanding rural broadband, 32.7 percent of Black respondents and 33 percent of Hispanic respondents only selected the federal government. On the other hand, older white participants were more likely, at 38.8 percent, to think that it took a more all-hands–on–deck approach: “It will take a combination of the federal, and city governments AND private companies to ensure high-speed internet is available to all U.S. citizens,” compared to 30.2 percent of all participants. Figure 15 details these findings.

Access to the internet

Study respondents were also largely connected to some type of internet due to the poll limitations of the KnowledgePanel (see notes in Methodology section). While most respondents reported access to high-speed broadband (69.2 percent), 30.8 percent did not. To measure access to home broadband, we asked respondents if they used high-speed broadband internet service, such as DSL (Digital Subscriber Line), cable, fiber optic, dedicated fixed wireless, or other services to access internet service at home. We also asked respondents to measure what percent had access to dial-up internet service (4.2 percent) or satellite internet service (8.5 percent). (See Figures 7 and 8.)

With regards to mobile connectivity, most respondents (53.6 percent) frequently used a smartphone to access the internet, which closely mirrors observed trends of mobile dependency for low-income households. Findings from Pew Research found that the less affluent are more likely to use smartphones to apply for jobs or complete schoolwork. As of early 2021, for adults in households earning less than $30,000 a year, 27 percent are smartphone-dependent internet users.121 Figure 9 presents findings related to smartphone use.

Income and race also tended to affect access to broadband for rural respondents (Figures 10 and 11). The median age for broadband access among the sample was also 18 to 29, with those under 50 having significantly less access to high-speed broadband (Figure 12).

General findings from sample