Editor’s Note: For Campaign 2012, Bruce Riedel and Michael O’Hanlon wrote a policy brief proposing ideas for the next president on America’s foreign policy toward Afghanistan and Pakistan. The following paper is a response to Riedel and O’Hanlon’s piece from Vanda Felbab-Brown. Elizabeth Ferris also prepared a response arguing that a vital step in establishing security and stability in Afghanistan and Pakistan is meeting the long-term humanitarian needs of their people.

Michael O’Hanlon and Bruce Riedel correctly point out that an improvement in governance is critical for stabilizing Afghanistan. Indeed, without robust progress in governance, the security gains of the 2009 military surge and the reversal of the Taliban momentum will be lost, and Afghanistan could easily disintegrate into civil war after 2014.

Whoever is elected the U.S. president in 2012 will need to stimulate and institutionalize improvements in governance, while repairing the fractured relationship between Kabul and Washington. Success depends on Washington’s conveying, with more credibility and effectiveness than it has managed so far, that it is committed to a stable and reasonably well-governed Afghanistan post-2014, including by committing U.S. troops and conditional aid.

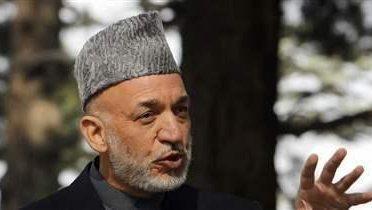

Afghanistan is heading for a triple earthquake of insecurity in 2014 stemming from: (1) the likely decrease in foreign combat forces, (2) the constriction of economic aid driven by these troop reductions and by fiscal austerity measures imposed by the United States and other donor countries and (3) an uncertain political transition at the end of President Hamid Karzai’s second term.

O’Hanlon and Riedel are correct that the next president must hold President Karzai to his promise not to alter the Afghan constitution and seek a third term. But, the necessary improvements in governance require more than overseeing a change in the Presidential Arg Palace. If President Karzai is merely replaced by a close ally, such as one of his brothers, the widespread perception among Afghans that the country is governed by mafia rule will persist. Nor is improving governance merely a matter of rebalancing power between the Arg Palace and the Afghan parliament, largely populated by powerbrokers who put a what’s-in-it-for-me calculus ahead of the national interest.

Governance in Afghanistan post-2002 has been characterized by weakly functioning state institutions unable and unwilling to enforce laws and policies uniformly. Official and unofficial powerbrokers have issued exceptions from law enforcement to their networks of clients, who can thus reap high economic benefits. Political patronage networks have been shrinking and becoming more exclusionary. Ordinary Afghans have become disconnected and profoundly alienated from the national government and the society’s other power arrangements. They are deeply dissatisfied with Kabul’s inability and unwillingness to provide basic public services and with the widespread corruption of the power elites. Local government officials have had only a limited capacity and motivation to redress the broader governance deficiencies. The level of inter-elite infighting, much of it along ethnic and regional lines, is at the decade’s peak. The result is pervasive hedging on the part of key powerbrokers, including the resurrection of semi-clandestine or officially-sanctioned militias.

Only a genuine broadening of the political system and strengthening of accountability at all levels can produce improvements in governance that can withstand the looming insecurity post-2014. The next U.S. administration must not fall into the trap of cynical misperception that corruption and abuse of power are endemic to Afghanistan and that Afghans are reconciled to them. It must not delude itself that outsourcing Afghanistan’s management to problematic warlords wearing the uniforms of police chiefs and other government officials can defeat the Taliban and produce stability. The extent of corruption requires prioritized focus on its most egregious forms and the resultant bad governance – namely, ethnic factionalization among the Afghan National Security Forces, tribal marginalization and fundamental human rights abuses by Afghan officials. However, prioritization does not mean that Washington can simply shrug off other forms of power abuse and profit-seeking and define them as “get-things-done” pragmatism.

Nor should the next U.S. administration allow itself to be beguiled by another seductive shortcut: the standing up of anti-Taliban militias in Afghanistan. Oft-repeated in Afghanistan history with overwhelmingly bad outcomes, the militias have only limited value on the battlefield, are prone to abuse and extort local communities. The next administration should think hard about how much to support the militia programs – and possibly work to roll them back. A corollary to reining in the misbehaving militias is to work diligently to improve the Afghan police and, critically, to direct them to combat widespread crime, instead of training them as light counterinsurgency forces.

Paradoxically, strategic negotiations with the Taliban, Washington’s new primary focus, could provide an opportunity for improving governance. But, that will be the case only if negotiations are designed as an inclusive process that brings in multiple political stakeholders, non-Pashtun ethnic groups and civil society representatives – not just those from women’s and Western-style non-governmental organizations, but also representatives of marginalized tribes and Islamist movements. To the extent that Washington seeks to strike a deal at all costs and that negotiations become close-to-the-vest bargaining among the United States, Afghan powerbrokers, Pakistan’s intelligence services and key Taliban factions, they will merely reward the Taliban’s military tenacity and produce neither improvements in governance nor national stability. A rush to a deal similar to the 1988 Geneva Accords, as U.S. military power and political leverage in Afghanistan diminish, will likely also end in a post-Geneva-like coda: civil war.

Structuring negotiations in a way that broadens political representation in Afghanistan will be very difficult. The negotiating process is easily subverted by a myriad of spoilers – from factions within the Taliban, to the country’s ethnic factions, to a mistrusting Arg Palace, to tribal factions and power cliques within the non-Taliban Pashtuns, to neighbors such as Pakistan. Nor is it clear at this early stage in negotiations that the Taliban is willing to settle for less than a return to national domination, in order to use the country as a platform for its Islamic Emirate ambitions. The next U.S. administration will also face the need to intricately balance maintaining enough military pressure on the Taliban to keep it genuinely interested in negotiations, as opposed to just running out the clock to post-2014, and in undertaking reciprocal confidence-building measures, such as ceasefires, that will be critical in producing success in the negotiations.

Finally, a drive to improve governance in Afghanistan also requires a careful handling of Afghanistan’s illicit poppy economy. The Obama administration wisely recognized that although the opium economy is one source of corruption, criminality, Taliban funding and economic distortion, blanket premature eradication redresses none of these problems and drives poppy farmers into the hands of the Taliban. Appropriately, the administration scaled back eradication efforts and focused instead on resurrecting legal agricultural production, while targeting Taliban-linked traffickers.

Unfortunately, serious implementation problems have plagued both aspects of the anti-opium effort, and the next administration will need to reform both. It must move beyond defining agricultural development as flooding a few districts with excessive, unsustainable political handouts and focus instead on sustainably addressing the structural drivers of the opium trade. Interdiction also must become far more selective and abandon the current tendency to target ordinary households.

The next U.S. administration cannot wash its hands of bad governance in Afghanistan and hope for a military success. Nor can it define good governance in ways that fundamentally contradict the human security of ordinary Afghans.