The Asia Pacific Economic Cooperation forum (APEC) has been a modestly useful government-to-government forum that has brought together nations from around the Pacific Rim since its inception in 1989. Sadly, hopes that APEC would provide a valuable arena in which to pursue the goal of open markets for trade and investment have fizzled. As the trade agenda has weakened, interest in APEC around the region has waned, and some nations have turned their attention to other regional or bilateral agendas.

As interest in APEC has ebbed, Asian nations have become more active in pursuing regional dialogues that exclude the United States. These alternatives include both an “ASEAN Plus Three” discussion and bilateral free trade areas between Asian countries.

Despite this malaise affecting APEC, the Bush administration should continue to take APEC seriously. The more narrow alternatives have the potential to harm American economic interests through diversion of trade and investment flows. With APEC, the U.S. government can pursue two tracks. First, APEC can play a useful role in the upcoming World Trade Organization (WTO) multilateral trade negotiations by reaching agreements that then can be moved to the WTO. Second, APEC can play an expanded role in regional financial discussions, helping Asian members to restructure their financial sectors in a manner consistent with the goals of the IMF.

POLICY BRIEF #92

President George W. Bush had a successful trip to the annual APEC summit meeting in October. The meeting provided him the opportunity to discuss the war on terrorism with Chinese Premier Jiang Zemin, during their first face-to-face meeting, Russian President Vladimir Putin, and leaders of nations in the region that have large Muslim populations, particularly Indonesia and Malaysia. However, the purpose of APEC was originally to discuss economic matters, especially efforts to lower trade and investment barriers around the region. That APEC has expanded to become a useful venue in which to discuss pressing security and diplomatic issues is a positive step. Nonetheless, having the economic agenda largely disappear is disappointing. The formal statements emanating from the economic discussion this year were particularly vague and devoid of content.

Lack of content in annual APEC agreements has diminished interest in the organization among policymakers. In Washington, mention of the organization gets little more than a yawn because its accomplishments have been either incremental or downright trivial. But it remains the broadest forum in which the United States can work with Asian countries. APEC may never become the central locus for decisive action on lowering trade and investment barriers, but the discussion of economic policy issues across the Pacific remains important, as does the opportunity for officials to meet their counterparts on a regular basis. It behooves the Bush administration to make APEC as effective as possible while admitting its limitations.

Should APEC fail as the central forum for regional economic policy discussions, the alternatives consist of regional or bilateral discussions within the Asian region that exclude the U.S. government and could, therefore, be detrimental to American economic interests. Thus, APEC remains useful as a mechanism for maintaining regular policy discussions that include the U.S. government. Furthermore, as a new WTO round of broad multilateral trade negotiations gets underway, APEC presents tactical opportunities to advance those unwieldy negotiations by hammering out bargains that can be presented to the WTO. Thus, the U.S. government may be able to adjust the APEC agenda to foster real action on trade and investment liberalization.

The History of APEC

APEC originated as a trade minister’s meeting in 1989, bringing together Asian nations with the United States, Canada, Australia, and New Zealand. For two decades, government officials, business people, and academics had argued in favor of creating an Asia Pacific trade and economic dialogue, but the inability to get Taiwan and China in the same room stymied those efforts. Only the end of the cold war made it possible to bring governments together, and several Latin American nations and Russia have joined APEC since its inception.

From the beginning, APEC adopted a novel concept of “open regionalism,” meaning that any reductions in trade and investment barriers adopted by APEC members would be applied on a “most favored nation” basis. That is, APEC members would agree among themselves to open up to the world and not simply on a preferential basis among themselves.

In 1993, President Clinton arranged an APEC heads-of-state meeting, which gave the forum much more visibility and which has become an annual event. In 1994, APEC members signed the Bogor Declaration, which set target dates for eliminating trade and investment barriers. Developed nation members of APEC pledged to eliminate trade and investment barriers by 2010, while the developing nation members would do so by 2020. In 1997, APEC members reached an important agreement on accelerated elimination of tariffs on information technology products. This agreement was forwarded to the WTO, where it was eventually adopted. A subsequent attempt to agree to accelerated tariff elimination on another set of products in 1998 failed, and since that time APEC has accomplished little.

To be sure, a modest agenda continues to create a more business-friendly environment across the Asia Pacific area. Numerous committees in APEC, with input from business participants, have worked on so-called “business facilitation” issues, ranging from online tariff schedules of APEC members to expedited customs clearance procedures. These sorts of fairly minor, technical issues are not glamorous, but they do bring together government officials from around the region in a useful fashion, and help to slowly build a more robust environment for regional business activity.

On the key issues of reducing and eliminating trade and investment barriers, however, APEC remains weak. A major problem has been the use of so-called individual action plans (IAPs) as the principal mechanism for moving toward the Bogor Declaration goals. That is, reduction and removal of trade and investment barriers does not occur as the result of bargaining among APEC members but as a voluntary, individual action by each member. With a somewhat distant target date, and no real negotiations, this process has yielded very little progress and plentiful cynicism.

Alternative Policy Forums

Asian commitment to APEC was dealt a blow by the 1997 Asian financial crisis. At the time, anger or disappointment with the United States and the International Monetary Fund (IMF) was quite strong. Some blamed Western speculators for engaging in unjustified speculation in Asian currency markets and causing the initial crash in the Thai and Indonesian currencies. Many felt that the IMF macroeconomic policy prescriptions demanded as a condition for aid were wrong, and were accompanied by structural reform demands that were too harsh. As a result, Asian nations have tilted away from APEC (with its broad membership including the United States) toward a dialogue among themselves that excludes the United States and other Western nations.

When the 1997 crisis hit, the Japanese government proposed that Asian nations form an Asian Monetary Fund (AMF) which would be either an alternative or a supplement to the IMF—the original proposal was unclear. Because this proposal was obviously motivated by disenchantment with the IMF, the U.S. government opposed it as antithetical to unified action in times of financial crisis. As a result, the Japanese government dropped its proposal.

In 1999, a new regional dialogue dubbed the “ASEAN Plus Three” group was formed, bringing together the members of the Association of Southeast Asian Nations plus China, South Korea, and Japan. The direction of this group’s dialogue still remains unclear. Its only concrete policy accomplishment so far has been the Spring 2000 Chiang Mai Initiative, an agreement in principle for the central banks of this group to reach expanded swap arrangements in order to enhance the ability of individual Asian central banks to fend off speculative runs on their currencies. A process of reaching these new bilateral agreements is now underway, although it is progressing slowly.

The ASEAN Plus Three group is actually the same set of nations that Prime Minister Mahathir of Malaysia proposed for his East Asian Economic Caucus (EAEC) group a decade ago. At that time, the U.S. government vigorously and publicly opposed his initiative, leaning heavily on the Japanese government not to participate. With American opposition, the EAEC did not come to fruition, though the vocal opposition left lingering bad feelings around the region. Today, the EAEC exists under the guise of the ASEAN Plus Three group.

The other development in the region has been increased talk of bilateral free trade agreements between Asian countries; Japan is the most noticeable advocate of this new policy direction. Japan’s trade agenda in the past had focused on the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade, the WTO, and the creation of APEC. But the government is disappointed with APEC, and came through the financial crisis with deep misgivings about American and IMF policies. Government officials, noting that Japan is the only major economy with no bilateral or regional free trade areas anchoring its international trade policy, decided by 2000 that the time had come to follow the lead of the United States and European nations. The first step has been a free trade area with Singapore (paralleling similar negotiations between Singapore and the United States), with negotiations leading to basic agreement in October 2001 and a formal agreement expected by the end of the year. Preliminary, unofficial discussions have proceeded between Japan and South Korea as well, though actual negotiations for a free trade area remain uncertain. Meanwhile, the November 2001 ASEAN Plus Three meeting provided the setting for China and ASEAN to announce an intent to negotiate their own free trade area (FTA).

At the moment, the deep economic and political divisions among Asian nations suggest that neither ASEAN Plus Three nor some of the regional or bilateral FTAs (other than Japan-Singapore) are likely to successfully promote regional cooperation. Japan, for example, spent most of 2001 engaged in a protectionist trade spat with China, refused to include agriculture in its FTA with Singapore, and irritated all of its neighbors with various actions that reflected its unwillingness to come to terms with its militarist past.

An Asian Monetary Fund?

A key motive behind the Chiang Mai Initiative on currency swaps has been to insulate Asian nations from the behavior of Western “speculators” and the policy demands of the IMF. This is a scaled-back approach from the AMF proposed by the Japanese government in 1997, but the motive remains the same. In fact, talk of an AMF has not disappeared, though the concept is now carefully couched in terms of making it a clear subsidiary or supplement to the IMF—disbursing funds to troubled Asian countries only with IMF approval. Still, there is an underlying desire to gain more independence from IMF or Western demands.

Japan’s position as a participant in an AMF heightens the undesirability of a separate regional financial arrangement. If an AMF or even some less formal regional financial cooperation comes into existence, it would place a group of Asian debtors together with Japan, the key developed-nation creditor located within the region. The potential in such an arrangement for the Japanese government to pursue policies that protect Japanese private sector interests to the detriment of those of American and European creditors is high. During the Asian financial crisis, the Japanese government was clearly willing to extend credit without the stringent conditions for economic reform attached to IMF loans. Despite assurances about subordination of any regional arrangement to the IMF, the strong temptation would remain to cut special deals to ensure that Japanese business interests were protected in a future crisis.

The U.S. Interest

American interests lie in promoting a peaceful and prosperous Asian region, a goal that had appeared to be moving forward until the Asian financial crisis of 1997. Trade and investment liberalization has been a core part of U.S. policy toward the region. This policy provided direct benefits to American firms, but also benefited the recipients in the form of cheaper imports and access to foreign capital. The process of financial liberalization was flawed, as demonstrated by the 1997 crisis, but the “win-win” approach of American emphasis on trade and investment liberalization remains broadly valid.

If Asian nations, in their reaction to IMF policy demands, move to slow progress in creating robust economic institutions while insulating themselves from foreign policy pressures, they would only hurt themselves. The United States must maintain a low profile on this issue in public, while working behind the scenes to ensure the primacy of the IMF as the voice of creditors toward debtor nations. The IMF can certainly be criticized for policy mistakes it made in 1997, but the solution lies in reforming the IMF, not in having groups of nations form institutions independent of the IMF.

On the trade side, the United States has long been committed to reduction of trade and investment barriers around the world, of which policy toward the region has been a subset. That goal has moved forward at the global level (through the WTO) at a regional level (such at the European Union) and bilateral free trade areas. Free trade areas have gained some popularity in the past decade. However, all narrow free trade arrangements involve trade diversion—enhancing trade opportunities for firms in the participating nations while disadvantaging firms from nations not party to the deal. American business would face the negative impact of such diversion should some subset of Asian nations overcome the problems discussed above and form preferential arrangements among themselves.

Despite trade diversion concerns, the United States has clearly moved in the direction of free trade areas itself, creating the North American Free Trade Area with Canada and Mexico, and now discussing a broader Free Trade Area of the Americas. Advocates of this approach see narrow free trade areas eventually coalescing, yielding the functional equivalent of a global reduction in barriers. Opponents worry about trade and investment diversion and foresee a complicated patchwork of FTAs around the globe that never coalesce and disadvantage those left out (such as poor African nations). American policy favoring FTAs now appears firmly entrenched, making outright opposition to similar developments among Asian nations a matter of inconsistency or hypocrisy.

Nevertheless, the potential for trade diversion that is detrimental to American interests is a real possibility in Asia. The ASEAN Plus Three nations plus Taiwan absorbed 18 percent of American exports in 1981 and 22 percent in 2000. Meanwhile, this region was the source of 25 percent of American imports in 1981 and 32 percent in 2000. Diversion would be more serious should an FTA also lead to preference in direct investment, damaging the ability of American firms to operate within the FTA.

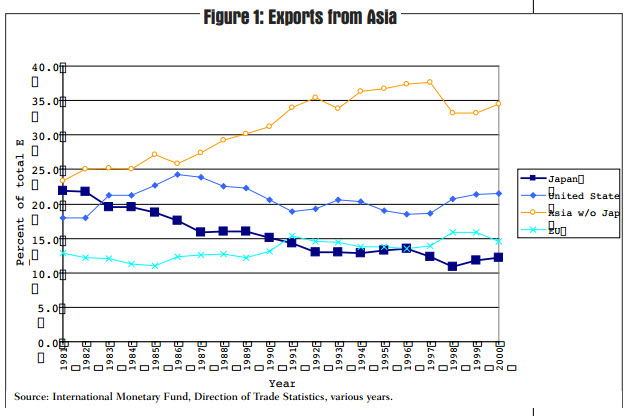

Narrow regional groupings might not be in the interest of Asian nations, either. Proponents have pointed to a rise in intra-regional trade, arguing that the trend should be endorsed or promoted by regional trade agreements. The implication of this argument is that the relative strength of trade ties with the United States or other developed Western nations has diminished. This, however, is most emphatically not the case. As shown in figure 1, Asian nations other than Japan have maintained large and relatively constant trade connections with the United States and Europe, while their ties to Japan have actually atrophied. Trade among Asian nations other than Japan has risen sharply, though much of that increase comes from China—whose integration into regional and global trade has been one of the seminal events of the past two decades.

Narrow regional groupings might not be in the interest of Asian nations, either. Proponents have pointed to a rise in intra-regional trade, arguing that the trend should be endorsed or promoted by regional trade agreements. The implication of this argument is that the relative strength of trade ties with the United States or other developed Western nations has diminished. This, however, is most emphatically not the case. As shown in figure 1, Asian nations other than Japan have maintained large and relatively constant trade connections with the United States and Europe, while their ties to Japan have actually atrophied. Trade among Asian nations other than Japan has risen sharply, though much of that increase comes from China—whose integration into regional and global trade has been one of the seminal events of the past two decades.

A principal reason for forging a regional free trade grouping would be to tie these nations more closely to Japan. But why forge a special tie with a country that has become relatively less prominent in trade over the past two decades’ More importantly, why do this at the relative expense of diverting trade away from the existing strong connections with the United States and Europe?

Policy Recommendations

The obvious starting point for American policy toward Asia is at the global level. On trade, the Bush administration has taken the right approach by pressing other governments for the start of the next round of multilateral trade negotiations within the context of the WTO. When this new multilateral trade round begins, some of the energy now being spent on regional and bilateral deals will be diverted back to the WTO. The prospect for a new WTO round presents the opportunity for using APEC as a sounding board or caucus that can facilitate agreements on reduction in trade barriers that can ultimately be bounced up to the broader WTO discussion.

On finance, the core goal should be to work on reforming the IMF and World Bank in order to decrease the chance that disaffected Asian nations will continue to pursue regional alternatives that exclude the United States. Nevertheless, there is room for a regional approach to Asia. Because the United States has a large and growing economic relationship with the region, a discussion separate from the global policy approach—with APEC as the vehicle—is warranted. In particular, APEC can complement the IMF by helping the developing nations of Asia with the restructuring of their financial sectors through adoption of better rules and regulation. This would help diminish the probability of future financial crises.

My earlier policy brief with Kenneth Flamm (“Time to Reinvent APEC,” Brookings Policy Brief No. 26, November 1997) urged that APEC follow that route, though as noted above, nothing has happened. The possible realm of issues on which even APEC nations will reach agreement for accelerated market opening may be limited, but even a limited action would help reenergize APEC in the long term and enhance the WTO negotiations.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).