Executive Summary

In 2018, we face an international security environment measurably worse than that of a mere five years earlier. Increased war-related violence accompanies an international order under challenge and rent by tensions. Global conflict deaths peaked in 2014 at magnitudes second only to the Rwandan genocide during the post-Cold War period. Proxy wars in Ukraine and Syria are reminiscent of the great-power-fueled conflicts of the Cold War.

However, this does not signal a universally more unstable world. Rather, violent conflict is concentrated in specific regions and reflects specific challenges. Four key features of today’s security environment, and one key emerging threat, deserve closer attention from the U.N. and other international actors.

1. New conflicts in the Middle East and North Africa account for the overwhelming majority of the increase in global battle deaths and conflict incidence.

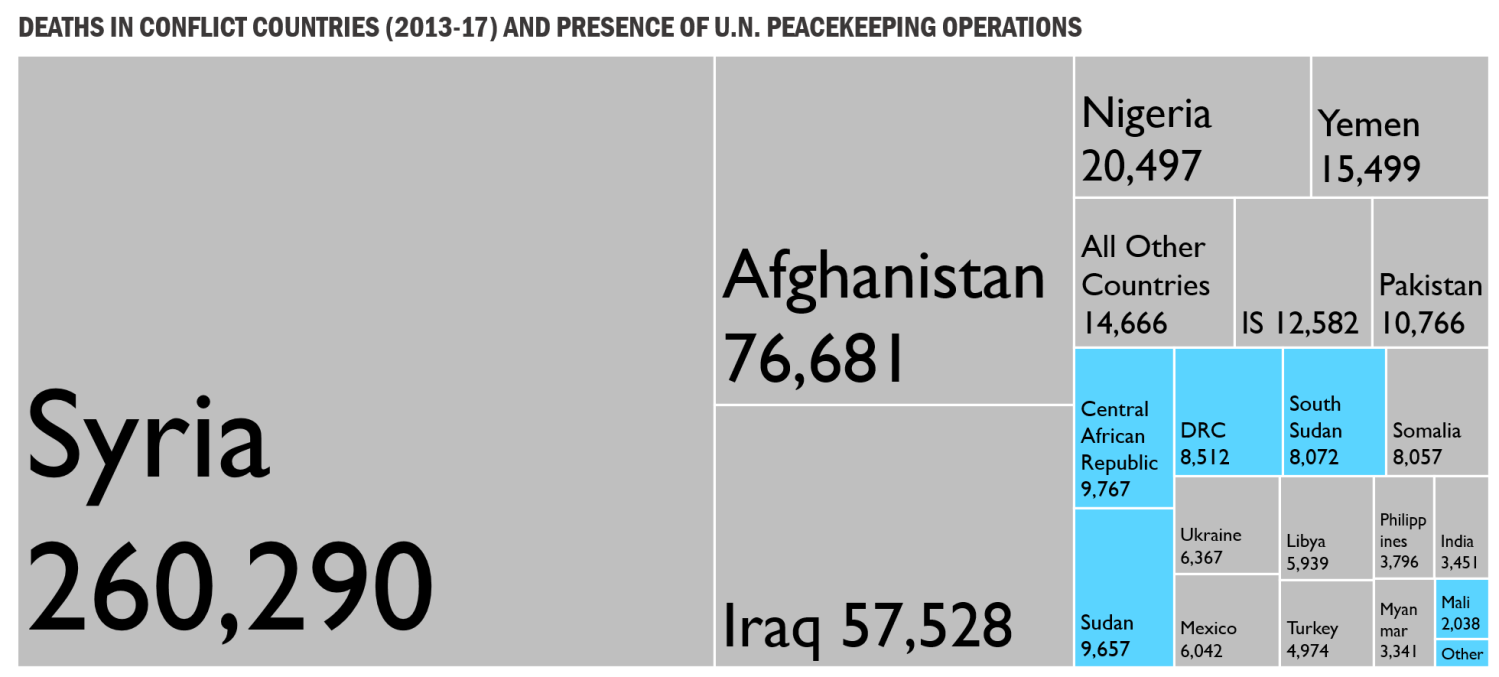

Conflict has not intensified in most of the world. This regional surge is due primarily to the civil war in Syria and the emergence and spread of the Islamic State and other extremist groups in and beyond Syria, Iraq, Yemen, and Nigeria. The number of conflicts in both the Middle East and Africa doubled between 2010 and 2015, while the Middle East alone accounted for 68 percent of all battle deaths during the past five years (2013-17).

2. The fusion of civil wars and terrorism, including on the African continent, introduces a complex new challenge to peace and security operations.

The spread of ISIS and other terror-linked Islamic extremist groups is a key factor in the rapid increase in conflict incidence. In 2015, the entire spike in global conflict incidence was due to the proliferation of ISIS to 11 new countries— not the outbreak of independent conflicts in these countries. The exigencies of simultaneously attempting stabilization efforts, humanitarian operations, and counterterrorism campaigns have proven vexing for national and international policymakers. The terrorist tactics and transnational aspirations of these organizations call into question the relevance of conventional state-building peace operations and diplomacy aimed at negotiated settlements.

3. To the detriment of global peace, United Nations peacekeeping operations have become increasingly removed from tackling today’s evolving security challenges.

Current U.N. peacekeeping operations are not addressing the world’s most pressing wars. Instead, they are deployed in countries that suffered only 7 percent of total global conflict deaths over the past five years. Of course, U.N. diplomatic efforts have taken place in many of these conflicts, terrorism is a complicating factor, and external sponsorship of warring parties has prolonged some of these conflicts. Nevertheless, the Security Council has proven unwilling or unable to authorize U.N. actions in these difficult wars, and U.N. troops remain underprepared to protect themselves and execute their mandates, much less take on emerging transnational terrorist threats—as highlighted by the Dos Santos Cruz report.

4. The U.N. confronts renewed great power tensions and the concomitant heightened risks of major warfare, including with nuclear armed states, and of widening proxy warfare.

Great power tensions have especially affected areas of strategic interest to regional and global powers, such as Eastern Europe and East Asia. Strategic crises in the Middle East, Iran, and the Korean Peninsula have absorbed great power attention, adding to the tensions of the moment and undermining cooperation in the U.N. And although total global military spending has remained largely unchanged since 2010, rising Chinese and potentially American arms spending signal risks ahead. Long-standing norms surrounding humanitarian law and the use and proliferation of weapons of mass destruction are being challenged.

5. Frontier threats in emerging technology, and specifically cyber tools and artificial intelligence (AI), pose an imminent and growing challenge to global security.

Commerce, communications, individual privacy, intellectual property, and critical infrastructure all depend upon tools vulnerable to cyberattacks. With the diffusion of information technology, even non-state actors already possess offensive cyber capabilities. Cyberattacks can be difficult to trace and attribute, and even when they can be, legal and ethical questions persist on what constitutes proportional state response. Currently, the U.N. possesses few tools with which to monitor or regulate either state or non-state uses of cyber weapons. AI presents further challenges: first, AI technologies are likely to reshape the global economy, and the economic impact of the resulting employment shift could result in political instability. Second, advances in AI will likely be used in weapons development in the form of autonomous systems. Decreasing costs will drive the diffusion of these weapons into the hands of non-state groups. Finally, the concentration of AI research in China and the United States and the first-mover advantage inherent therein has substantial implications for the future development of the international economic and security order.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).