As the COVID-19 pandemic exacerbated economic insecurity for millions of people across the U.S., many cities instituted policies and programs aimed at providing some relief to individuals and families. These include policies that temporarily halted fines and fees collections, which disproportionately impact Black and Latino or Hispanic communities.

Fees are often used as a surcharge to fund local government services, and fines—such as parking tickets—are a form of punishment for violating a municipal code or law. Even before the pandemic, there were many individuals who had to choose between paying such tickets and paying rent, utilities, or groceries. While halting fines and fees collections provided relief to some, it was only temporary, and the need to rethink local government revenue collection practices remains.

As a result of American Rescue Plan Act (ARP) funding, cities currently have the flexibility to make significant investments that can build up the economic reserves of individuals and families, particularly lower-income ones. The problem is many of these efforts to support low-income populations can be undone by inequitable revenue-raising practices.

Below are six recommendations on how local government leaders can begin to reform their fines and fees practices.

Listen to the people directly impacted by fines and fees

One way to begin reforming fines and fees practices is by establishing a working group comprised of individuals who have been directly impacted by existing policies. Residents, community-based organizations, advocacy groups, and local government department staff should also be included, so stakeholders are involved throughout every step of the policy design, reform, and implementation process.

Local leaders in Chicago and San Francisco, for example, began their fines and fees assessments and reform processes by bringing together city departments, elected officials, community organizations, and residents to collaborate on solutions. Once the working group is formed, stakeholders can develop principles, research topics, and potential solutions together.

Additionally, policymakers should speak with residents outside of the working group to understand their experiences with fines and fees policies, as well as residents’ specific pain points. A focus group discussion, community listening session, or even a town hall meeting can serve as a format for achieving this. The Chicago city clerk’s office, for instance, conducted focus groups in neighborhoods most affected by regressive fines and fees policies. They were also conscious of how these groups and individuals shared space with one another, intentionally seating everyone in a circle and mixing government staff with residents and advocates so everyone was on equal footing and could better communicate with one another.

Working group meetings and community listening sessions can be organized and scheduled in many ways; Figure 2 presents one such framework for how government leaders and advocates can schedule monthly meetings and community listening sessions.

Figure 2. Example framework for establishing working group meetings and community listening sessions

| Month | Working Group | Community Listening Sessions |

| 1 | Launch the working group composed of directly impacted populations, community organizations, and government staff. Begin with introductions, setting group norms and principles, and an outline of research topics the group will review together. |

Identify parts of the city to host focus groups, community listening sessions, or town halls to hear from residents. Identify partners that can help with outreach and promotion.

|

| 2 – 5 |

Present one or two topics and any relevant research per meeting and discuss these findings together as a group.

|

Host focus groups, community listening sessions, or other public meetings. |

| 6 | Present a draft report to the working group and incorporate feedback into the final report. | Incorporate the focus group’s findings into the report. |

Source: Author

Gather information and build a long-term data collection process

To prioritize reform areas and support the working group’s efforts, local government staff should conduct an internal review of their existing fines and fees policies. Interviews should be conducted with government staff responsible for revenue collection and budget management, as well as frontline staff who interact with residents. Policymakers should also consult with other local governments that have undergone reforms in order to gain an understanding of their successes and challenges. For example, before starting their own reform efforts, Chicago officials reached out to the San Francisco treasurer’s office to learn more about the San Francisco Financial Justice Project and their fines and fees reforms.

In addition to collecting data in the short term, decisionmakers should also consider the long-term benefits of integrating data collection into existing processes and creating transparency by making data public. San Francisco, for instance, now reviews fines and fees during their annual budget process.

During the beginning phases of fines and fees data collection, policymakers may collect data and information on a case-by-case basis. However, government staff should work toward establishing long-term and sustainable data collection processes, so they have this information at their fingertips during future fines and fees reviews.

Break the problem down into smaller components

When it comes to fines and fees policies, determining where to even start the reform process may seem daunting. Thus, it may be helpful to break the fines and fees landscape down from broader categories into more specific ones:

- Transportation fines and fees such as parking tickets, speeding, and other traffic-related tickets, which can have misaligned incentives that lead to disproportionate ticketing.

- Criminal justice fines and fees such as court fees, fees for making phone calls in jail, or fines and fees issued when exiting jail.

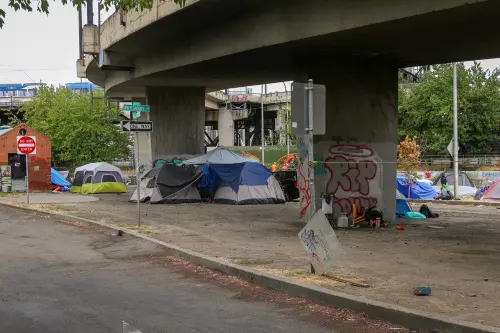

- Quality of life fines and fees such as utilities and water fines and fees, but also those that criminalize poverty and people experiencing homelessness.

- Collateral consequences of unaffordable fines and fees such as car-impoundment-related fees (booting, towing, and storage fees) or debt-based driver’s license suspensions.

Determine the unit of government responsible for setting the specific fine or fee

Having a clear understanding of which government unit or department is responsible for setting a particular fine or fee, what authority they have to change their policy, and how they can contribute to a reform process all can assist the working group and policymakers. It may be, for instance, that the city is responsible for levying transportation fines and fees through its police and parking enforcement staff, whereas the county might be responsible for levying criminal justice fines and fees. Moreover, after determining the unit of government responsible for setting a specific fine or fee, one can identify whether the problem stems from the policies themselves or their administration. And subsequently, one might consider reviewing the policy based on every interaction point a resident might have with government.

Take parking tickets, for example. A policymaker may examine whether different ticket amounts or policies such as doubling ticket amounts have an impact on revenue collection and residents. They can also study the sources of excessive ticketing practices, particularly those involving an overconcentration of police in certain neighborhoods. Moreover, they could review revenue collection processes to determine whether residents experience barriers to paying their tickets, such as burdensome payment plans, inconvenient operating hours, or complicated payment systems.

Figure 3 shows some sample questions that can help analyze revenue collection processes using the parking tickets example, though the exercise can be applied to a wide variety of topic areas and policies.

Figure 3. Example questions to analyze broad fines and fees topics

| When the Ticket is Issued | When the Ticket is Contested | When the Fine is Collected | |

| Resident and government interaction point | A resident might interact with law enforcement or parking enforcement. | A resident might contest their ticket at an administrative hearing or traffic court. | A resident might pay their ticket with frontline staff of a department in charge of revenue collection. |

| Policy | What is the ticket amount and how is it determined? Why? | What is the deadline for paying the ticket or contesting it? Can it be extended? |

|

| Administration |

|

|

|

Source: Author

Following the example analysis above, Chicago’s working group examined the city’s ticketing practices for non-moving violations such as parking tickets and tickets for failing to purchase an annual “city sticker” or vehicle decal. The working group developed their solutions by reviewing existing policies, ordinances, rules, and regulations; studying comparable policies in other cities; discussing potential solutions with relevant department staff; and asking residents about their experiences at various interaction points with government to better understand compliance barriers.

Chicago’s earliest reforms included ending driver’s license suspensions for unpaid parking tickets and ending the policy of doubling the $200 fine for drivers who failed to purchase an annual city sticker. Officials also overhauled their parking ticket payment plans, making them more affordable and accessible. Though Chicago is still in the process of fully reforming its fines and fees policies, these were important first steps led by advocates, residents, and community-based organizations.

Be open to challenging assumptions and historical precedent

Local leaders should question existing assumptions undergirding policies and administrative procedures on fines and fees. For example, take data analysis regarding parking ticket debt owed to the city: When interpreting data showing that residents in certain parts of a city are not paying their parking tickets, policymakers could assume those residents are intentionally skirting the law. Based on this assumption, policymakers might decide to crack down on these presumed bad actors by doubling their fines, placing boots on vehicles, or towing them.

Alternatively, however, policymakers might challenge the assumption that residents are intentionally skirting the law and consider instead whether there are other reasons why someone has not paid their parking ticket. Perhaps a fine or the existing payment plans were unaffordable, as Chicago policymakers found. These alternative explanations could lead to entirely different policy solutions. If the goal of a fine is to change resident behavior or get them into compliance with the law, local leaders should determine the reasons for nonpayment rather than rely on assumptions. Talking to residents or holding community listening sessions can also help policymakers better understand resident behavior.

Local government leaders must also be willing to challenge historical precedents. Consider traffic stops: Recently, The New York Times reported on how the demand for fines and fees revenue can shape and drive police traffic stops. Given that reporters also documented how many police traffic stops can become dangerous or fatal, local governments should be open to imagining what traffic enforcement could look like without police. Some scholars have proposed frameworks for decoupling traffic enforcement from police functions, and Boston’s newly elected Mayor Michelle Wu has proposed civilianizing traffic stops. Meanwhile, local leaders in Berkeley, Calif. are investigating existing practices within their police department as they aim to reduce or eliminate the use of police officers to enforce traffic infractions.

While challenging historical precedents may not result in major reforms in the short term, beginning this review process could lead to new insights or even alternative approaches over the long term.

Consider ways ARP or philanthropic funds can help local governments achieve their reforms

Local leaders have several options for using ARP funds to support their fines and fees reform efforts, including aligning their funding or obtaining matching grants from other funders, such as through philanthropy. For further guidance on the ARP, compliance, and reporting requirements, the Treasury Department provides a regularly updated FAQ. Some key areas where funds, including philanthropic funds, could be allocated include:

- A cost-benefit analysis of current revenue collection practices to determine how much money the local government spends on collecting fines and fees revenue.

- A study to identify the sources of inequitable outcomes due to existing fines and fees policies, as well as a study to evaluate reform efforts.

- A pilot reform of existing payment plan options, such as lowering thresholds for entering into payment plans or establishing sliding-scale payment options, which take into account a person’s ability to pay a fine.

- A grant supporting the inclusion of residents and directly impacted groups as part of the policy development process.

In funding research, policymakers must be careful not to simply conduct studies for their own sake. Several studies and reports have already documented the disparity in outcomes—more research is needed to not only identify the sources of inequities but also to start addressing them.

Grants and ARP funds should also be used whenever possible to ensure inclusive participation in governance and decisionmaking. For example, small grants can be used to provide food, child care, and interpretation at public meetings and community listening sessions so more residents can participate. In Chicago, the Chicago Community Trust funded such participatory efforts, ensuring parents, immigrants, and directly impacted populations were included at decisionmaking tables to inform fines and fees policy reforms.

A pivotal moment for reforming fines and fees practices is here

To reform fines and fees practices, local officials can work with and listen to directly impacted populations on everything from parking ticket amounts to payment plans to utility fines and fees. Government leaders should ensure their fines and fees policies are equitable, efficient, cost-effective, and transparent, and numerous resources are available for them to do so. The Cities & Counties for Fine and Fee Justice Network, for example, provides webinars, roadmaps, and other resources for possible solutions.

Meanwhile, ARP funds are providing local leaders with ample breathing room and flexibility to ask broader questions regarding their budgets and revenue collection practices. Using the six considerations above, local government leaders should use this opportunity to begin long-overdue fines and fees reforms.