Fast track trade promotion authority has become the premier legislative vehicle for airing America’s ambivalence about trade and globalization. Opponents decry fast track as a blank check to pursue trade agreements that undermine hard won social and environmental protections. Proponents portray fast track as a litmus test of America’s international leadership. Fast track was intended to be neither. It was conceived as a procedural mechanism to enhance the president’s credibility in negotiating complex multilateral trade agreements by streamlining the congressional approval process in return for enhanced congressional oversight.

Fast track’s power derives from the underlying political compact between Congress and the president rather than its statutory guarantees, which are technically fragile. The convention of legislating an open-ended, time-limited grant of authority invites a regular, heated debate in the abstract over whether trade is good or bad and the relationship between trade and labor and environmental standards. This approach has led to eight years of stalemate and is polarizing the debate over the upcoming vote in the House. Far better to weigh the concrete benefits and costs in the context of specific agreements. The current impasse can be overcome through three procedural fixes: strengthening congressional input on trade negotiations, limiting the application of fast track to only those agreements whose complexity and scope warrant it, and targeting the congressional grant of authority and associated substantive guidance to particular agreements. Such procedural questions would likely be at the heart of any Senate debate.

POLICY BRIEF #91

The Debate

President Bush has signaled that fast track, or trade promotion authority, is his top legislative trade priority. Fast track has become the Moby Dick of American trade politics. Since it was last in effect, presidents and trade supporters have expended enormous political capital pursuing the great white whale, and the hunt for this elusive quarry at times has come close to capsizing the ship of American trade policy.

But is fast track the prize that its proponents claim it to be? Would its reenactment indeed bridge the chasm on trade? Or is the protracted stalemate a symptom of a more profound divide in American public opinion? The answers lie somewhere in the middle. Fast track is important precisely because it has become a political symbol of America’s commitment to free trade. Some trading partners now claim they are reluctant to enter into trade negotiations with the United States without fast track. This perception, however, stands in stark contrast to what fast track, as legislation, actually does. Fast track, originally conceived as a relatively narrow, procedural measure, did not authorize any agreements the president could not negotiate under his own constitutional powers, require inclusion of any specific provisions in any agreements, or guarantee ratification of any agreements. From a legal point of view, fast track is a highly conditional grant of authority.

Fast Track’s Origins

Fast track is the product of many years of rebalancing the responsibilities of the legislative and executive branches on international trade policy. Prior to the twentieth century, regulation of foreign commerce was almost exclusively a congressional prerogative. Tariffs were considered to be more a function of domestic tax policy than of foreign affairs and, as such, were subject to change only by an act of Congress. The president’s main responsibilities on trade were to collect the tariffs set by Congress and to negotiate bilateral Treaties of Friendship, Commerce, and Navigation, which extended to treaty partners the most favorable tariff rates available.

Recognition of the damage done by high tariffs around the world in the wake of the Great Depression marked a major change in U.S. trade policy. The landmark Trade Act of 1934 effectively “pre-approved” presidential authority to lower U.S. tariffs within certain limits by authorizing the president to enter into reciprocal tariff-reduction agreements. The law was extended 11 times through 1962.

Congress again expanded the president’s authority in the Trade Act of 1962, authorizing the elimination of certain U.S. tariffs in the Kennedy Round of negotiations under the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT). But authority was conditioned on enhanced congressional oversight and required the president to provide Congress with copies of agreements and the rationale for entering into them, and to accredit four members of Congress as part of the U.S. negotiating delegation. The Kennedy Round concluded successfully in 1967 with an array of tariff-reduction commitments, but also included two controversial “non-tariff” agreements governing antidumping and customs valuation, prompting some lawmakers to conclude that the president had overstepped his authority.

As a result, when Congress considered a new grant of authority for the GATT Tokyo Round, it decided to maintain final control over non-tariff agreements. In the 1974 Trade Act, Congress mandated that non-tariff agreements be implemented only through legislation, and that the president consult with Congress prior to entering into them. In return, to reassure trading partners and enhance the credibility of U.S. negotiators, Congress established new procedures to ensure a timely, amendment-free vote. Thus was fast track born.

How Fast Track Works

The provisions of past fast track laws can be loosely divided into three categories:

Congressional Oversight Procedures establish requirements the president must meet for fast track to apply. They enumerate overall trade negotiating objectives and industry- or issue-specific principal trade negotiating objectives that Congress expects U.S. negotiators to pursue. The principal objectives have changed over time to reflect evolving congressional priorities and are the focus of the current debate over labor and environmental standards. The oversight provisions also require the president to provide Congress with: notice before entering into negotiations or signing an agreement, prompt transmittal of the text of a proposed agreement, a statement certifying that the agreement advances Congress’s objectives, and an implementing bill as the vehicle for Congress to codify an agreement under U.S. law.

Fast Track Legislative Procedures establish limitations on Congress, ensuring a streamlined legislative process. It requires introduction of the implementing bill in both houses of Congress, referral to relevant committees (at minimum the House Ways and Means and Senate Finance Committees), and automatic discharge after 45 legislative days if the bill has not been reported out of the committees. Fast track permits no amendments to the implementing bill and limits floor debate to 20 hours in each chamber. It requires a timely vote on the implementing bill in the House and Senate no more than 15 legislative days after leaving committee and ensures no conference committee, since both chambers vote on the same implementing bill.

Methods of Withdrawing Fast Track allow Congress (or one house or a committee) to withdraw fast track from a trade agreement. Fast track can be withheld if there is a failure to meet the notice, consultation, transmittal, and implementing bill conditions described above. This may occur if a majority in both houses passes, within 60 days of each other, a procedural disapproval resolution on the basis of a failure to consult, which provides ample congressional discretion. The “gatekeeper” committee provision permits either the House Ways and Means or Senate Finance Committees to deny fast track application to a bilateral or regional agreement by voting a disapproval resolution within 60 days of the president indicating his intention to enter into negotiations. Fast track can be withdrawn outright at any time through unicameral repeal because it is considered an exercise of the House and Senate’s rulemaking power. Finally, sunset and extension provisions have limited fast track’s duration to five years. The most recent fast track legislation to be enacted, part of the 1988 Omnibus Trade Act, was more restrictive, providing a renewal for only three years, with a two-year extension subject to an extension disapproval resolution by either chamber.

The withdrawal provisions, seldom used, make fast track a highly fragile and easily retractable mechanism from a technical standpoint and underscore that the power of fast track in practice derives from the underlying political compact between Congress and the president. If the president appeared to violate congressional intent in negotiating an agreement, the withdrawal mechanisms could be triggered, sounding the death knell not only for fast-track review but likely also for the agreement itself.

Uses of Fast Track

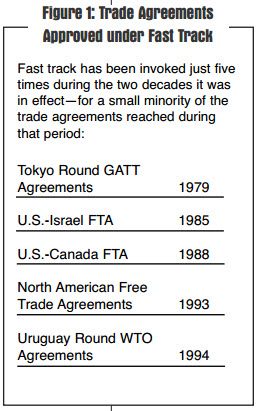

Despite its symbolic significance, fast track was invoked only five times during the 20 years it was in effect for a small minority of U.S. trade agreements (see figure 1). If the bulk of U.S. trade agreements can be implemented without fast track, it raises the question of whether fast track is necessary at all. Fast track agreements are not distinguished from other trade agreements by their size, complexity, or importance. For example, the bilateral agreement on China’s accession to the World Trade Organization, implemented without fast track, will affect far more trade than has the U.S.-Israel free trade agreement (FTA). Rather, what most distinguishes fast track agreements is the extent to which changes to U.S. law are required and to which Congress expects to be involved. But even this distinction, while broadly true, is qualified. For instance, the U.S.-Israel FTA was approved under fast track procedures while the nearly identical U.S.-Jordan FTA was not. This suggests there is a political overlay to these distinctions.

Despite its symbolic significance, fast track was invoked only five times during the 20 years it was in effect for a small minority of U.S. trade agreements (see figure 1). If the bulk of U.S. trade agreements can be implemented without fast track, it raises the question of whether fast track is necessary at all. Fast track agreements are not distinguished from other trade agreements by their size, complexity, or importance. For example, the bilateral agreement on China’s accession to the World Trade Organization, implemented without fast track, will affect far more trade than has the U.S.-Israel free trade agreement (FTA). Rather, what most distinguishes fast track agreements is the extent to which changes to U.S. law are required and to which Congress expects to be involved. But even this distinction, while broadly true, is qualified. For instance, the U.S.-Israel FTA was approved under fast track procedures while the nearly identical U.S.-Jordan FTA was not. This suggests there is a political overlay to these distinctions.

A Prescription for Progress

The fast track stalemate revolves around two central issues. Most attention is devoted to whether Congress can reach political accommodation on the substantive guidance it gives the president regarding the content of trade agreements&151;particularly on labor and environmental standards. The second issue is how to facilitate a productive relationship between Congress and the president in advancing America’s trade interests. The second issue deserves more attention than it has received and likely will be central to any Senate debate.

Procedurally, fast track can serve valuable purposes. America’s negotiating position is stronger when foreign governments are assured that complex trade agreements requiring extensive changes to U.S. laws will be given a fast up-or-down vote, and that meaningful congressional input will help shape agreements that have a better chance of commanding domestic support.

Is the current form of fast track the best way of doing this? The answer is almost certainly not. The main problem is the abstract nature of the fast track debate. Asking Congress for an open-ended grant of authority to pursue trade agreements whose benefits are as yet undefined and far into the future is a recipe for trouble. A powerful coalition of opponents has repeatedly mobilized effectively to thwart fast track legislation. But supporters mount a full counter-offensive only when there are concrete benefits in the offing. For example, in 1997 and 1998, with no trade agreement pending, fast track failed in the House, but in 1994, when the hard won gains of the Uruguay Round hung in the balance, the House voted overwhelmingly to approve it, with the support of nearly 60 percent of Democrats.

Neither the president nor Congress nor the American people benefit from this recurring debate. In seeking fast track, the president is inevitably compelled to make the case that it is vital to his ability to negotiate on trade. This gives foreign trade partners the perfect excuse to blame failure on the president’s lack of authority from Congress. And the succession of failed votes has put members of Congress in the no-win position of being forced to declare every few years whether, in the abstract, they are for or against trade.

It is counterproductive to turn fast track into a quest in its own right. Rather, the key is to find a pragmatic mechanism for negotiating and expeditiously implementing strong trade agreements. Is there a way to achieve a balance between enhanced congressional oversight and congressional procedural restraint without inviting the protracted stalemate seen for the past eight years? The answer is almost surely yes. A more effective fast track would require meaningful congressional input into negotiations, more selective application of fast track by the president, and closer targeting of fast-track provisions to particular agreements.

A. Enhanced Consultations

Congressional input and oversight on trade negotiations is accomplished only in part through the negotiating objectives. It is difficult not only to draft precise negotiating objectives in advance that could apply to very different agreements over several years, but also to evaluate after the fact whether the objectives have been adequately advanced for purposes of disapproval. In fact, there have been only two cases of a concerted effort to disapprove fast track for an agreement, suggesting the disapproval mechanisms are a fallback check rather than the first line of defense against the president’s ability to secure fast track consideration of a controversial agreement.

In practice, although negotiating objectives draw much of the fire and fury in the fast track debate, far more important are mechanisms ensuring meaningful consultations between the president and key members of Congress during negotiations. Former fast track rules were vague as to the extent, frequency, and timing of consultations. That must change. Strengthened procedures should provide for:

- The chairs of the Ways and Means and Finance Committees to establish detailed schedules and topics for consultations, which would intensify during critical junctures

- More formalized reporting and assessment of whether the executive branch is working in good faith to develop a negotiating strategy in line with congressional guidance

- The congressional trade advisers—called for under prior fast-track laws—to be required to consult regularly with the majority and minority leadership in both chambers and all committees having relevant jurisdiction to ensure broader congressional input

- Congressional advisers to be responsible for providing the president and U.S. negotiators with the sense of the Congress on the state of negotiations

- Members charged with oversight to devote adequate time, attention, staff, and resources to track negotiations that may involve thousands of products and more than a hundred countries

In addition, the creation of a nonpartisan group of professional congressional staff dedicated to trade would help make congressional oversight meaningful. Members now are highly dependent on the executive branch, the International Trade Commission, and the Government Accounting Office for analysis of trade. Greater in-house expertise would allow Congress to formulate innovative positions and provide relevant input as negotiations proceed, reducing the need to legislate detailed negotiating instructions in the abstract.

B. More Selective Use of Fast Track

Since 1999, the U.S. Congress has enacted six pieces of trade legislation in the absence of fast track authority. Moreover, the U.S.-Jordan FTA faced no attempt to introduce amendments despite being approved without fast track. In addition, a growing number of countries, including Chile, Singapore, and Australia, have indicated a willingness to negotiate free trade agreements with the United States without the safety net of fast track. This record suggests there is greater scope to secure approval of trade agreements without fast track than is generally acknowledged, and that the president could be more selective in the agreements for which he seeks fast track. Only those agreements that require extensive changes to U.S. laws and involve multiple partners—such as the global trade negotiations launched this month in Doha—hinge centrally on fast track procedures. Since such agreements are rare, important, and years in the making, it is reasonable for Congress to expect the president to provide specific information in advance on how the authority will be used. Perhaps the Bush administration erred in immediately making broad trade promotion authority its top priority, rather than first putting its own stamp on the trade agenda, specifying a limited set of agreements that would need fast track, and ensuring these initiatives were ripe for congressional scrutiny.

Presidents would be well advised to postpone seeking fast track until a compelling case can be made that contemplated negotiations will yield agreements of sufficient complexity and scope to necessitate fast track. Conversely, the president should continue to seek—and Congress should continue to grant—fast track authority for particular agreements that truly merit it. It would be extremely detrimental to U.S. leadership if the current impasse continued, encouraging negotiation of only those agreements that are sufficiently uncontroversial that they would not risk being picked apart by Congress under normal procedures.

C. Congressional Oversight: Targeted Fast Track

The biggest challenge is to strike a better balance on fast track oversight provisions. In principle, Congress has the authority to withhold fast track treatment on the simple grounds of “failure to consult.” But in practice, although Congress has repeatedly failed to grant approval for renewal of general fast track authority, it has never withheld fast track procedures on a pending agreement. This suggests that Congress is more uneasy providing broad authority that could be used in unanticipated circumstances than with the actual agreements that have been submitted for consideration. As long as fast track must be defended on the basis of the worst agreement that might be submitted, reenactment will remain difficult.

But critics are incorrect in assuming that fast track is a blank check. The Senate Finance Committee wrested major concessions before permitting negotiations with Canada to proceed, and although resolutions disapproving NAFTA failed in committee, the underlying concerns were addressed in the negotiating endgame. These are only the most extreme examples of the president making accommodations to overcome congressional opposition; cases where course corrections preempted incipient congressional action are likely far more common.

There is an inherent tension between making fast track sufficiently flexible to apply to a broad variety of potential agreements and sufficiently precise to convey the substantive expectations of an often divided Congress. Mandate too much detail and fast track applies a one-size-fits-all approach to widely diverse agreements, forcing Congress into a contentious and often paralytic debate over the abstract dimensions of trade. But fast track without details and precision inevitably runs the risk of abdicating congressional oversight.

Currently, this is most apparent in the debate over labor and environmental standards. The treatment of these issues conveys an important political statement, determining their priority. But it is unclear that a workable paradigm for these complex matters can be neatly inserted into a fast track law designed to cover a wide array of agreements and countries where levels of development and commitment to social and environmental protections vary widely.

Striking the right balance hinges on the interaction of several provisions of fast track: the duration, the scope, the precision of the negotiating direction given to the president, and the mechanisms for withholding fast track treatment from a particular agreement. There are likely to be several different combinations that could be comparably effective in more closely targeting the substantive debate to particular agreements, while retaining the procedural value of greater cooperation between the branches.

One alternative would be to make each grant of authority specific to the negotiation of a particular agreement and the duration coterminous with the length of the negotiation. This would permit much more precision in the negotiating objectives. It would also allow Congress to confine debate to the potential merits of a particular trade agreement. However, it might prove overly restrictive, unintentionally signaling that the president does not have the authority to enter into any launch of negotiations until after congressional approval had been obtained.

At the other end of the spectrum, Congress could establish fast track procedural mechanisms for a longer duration or even indefinitely, but require an additional hurdle for the application of the procedures to a particular agreement. This would push the president to consult Congress at the start of (or early in) negotiations, and it would permit Congress to establish more specific negotiating objectives for each agreement than is possible in omnibus fast-track legislation. Congress could further hone the balance by specifying whether the application to a specific agreement would require a vote by only the “gatekeeper” committees or set a more difficult threshold of floor action, and whether it would require a vote of approval or the easier standard of withstanding possible congressional disapproval. The degree of congressional oversight afforded by the hurdle for application to particular trade negotiations could be made directly proportional to the overarching authority granted the president by Congress.

Providing Congress with strengthened oversight on specific agreements in return for a more durable procedural agreement between Congress and the president would go a long way toward breaking the unproductive stalemate that has characterized the last several years.