Content from the Brookings-Tsinghua Public Policy Center is now archived. Since October 1, 2020, Brookings has maintained a limited partnership with Tsinghua University School of Public Policy and Management that is intended to facilitate jointly organized dialogues, meetings, and/or events.

Cold War analogies for describing U.S.-China relations are appealing for their simplicity and clarity. But they are misleading and counterproductive for dealing with the real challenges that China’s actions pose to good governance around the world, writes Ryan Hass. This piece originally appeared in the Taipei Times.

In recent weeks, there has been an uptick in debate about the role of ideology in the intensifying U.S.-China rivalry. Many commentators in the United States and around the world have heralded Vice President Pence’s Oct. 4 speech on China as the starting gun of a new Cold War.

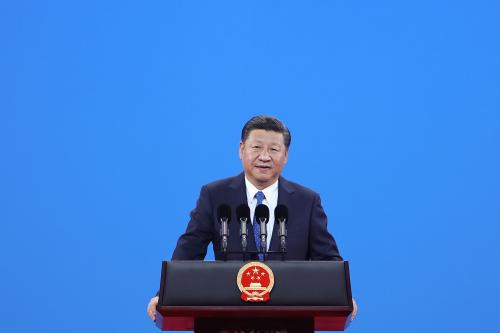

There is some truth to the Cold War comparisons. Ideology is becoming an area of contestation in the U.S.-China relationship. For example, Chinese President Xi Jinping (習近平) invoked the concept of a “China model” as an alternative to liberal democracy in his speech to the 19th Communist Party Congress in October 2017. In his recent speech, Vice President Pence placed ideological issues at the center of his message, promoting the concept of a “free China,” calling out Chinese abuses of its citizens’ human rights, and lifting up Taiwan as a political model for the mainland. And in a departure from his predecessors, President Trump has adopted an increasingly zero-sum approach toward China, seemingly making efforts to limit China’s rise an organizing principle for his overall policy.

Even though the U.S.-China relationship clearly has become more adversarial, it still stands a significant distance apart from Cold War analogies. Unlike the Cold War, there are no proxy conventional wars being waged in third countries. Neither country’s nuclear arsenal is on hair-trigger alert to respond to a surprise nuclear strike from the other. There is deep people-to-people contact, and both economies remain fundamentally interconnected. Neither country is mobilized to win an existential, universalistic, winner-take-all ideological battle between authoritarian capitalism versus liberal democracy. And in a cross-Strait context, the intensity of ideological struggle now pales in comparison to the situation during the Cold War.

No question, China wants to make the world safe for its form of governance. Beijing craves external validation as a source of domestic legitimization for its governance system. China certainly welcomes others to emulate its policies, and pressures countries not to challenge its governance model, its “core interests,” or its human rights record. China also is ruthlessly opportunistic and amoral in advancing its strategic and economic interests abroad. But even these efforts fall short of the Soviet Union’s aggressive use of carrots and sticks to pull countries into a Marxist-Leninist orbit during the Cold War.

Some analysts disagree, contending that Xi’s invocation of a “China model” was a clear marker of China’s ambitions to challenge liberal democracy. Some in Beijing may harbor such grand ambitions. Even if they do, though, they are unlikely to achieve them. The China model is unique to China. It is the product of 5,000 years of continuous civilization, a unique governance tradition, and the hard work of 1.4 billion people. No other country shares these same attributes. And to date, no other country has found the model to be an object of emulation. Not even ethnically Chinese societies like Taiwan and Singapore see the model as appealing.

But here’s the rub: China’s ideological (non-) attraction may not present an immediate challenge, but China’s actions do. By extending cheap financing to countries with poor records on rule of law and cultures of corruption, China is giving developing countries an alternative to the types of conditions-based assistance that have become the norm among multilateral development banks, the United States, and other donor countries. In so doing, China is amassing leverage for future use, and also enabling some leaders with bad track records on transparency and rule of law to continue behaving badly. Venezuela is a case in point. Zimbabwe is another.

Additionally, China is pioneering the fusion of censorship and surveillance technology with government policies to stifle dissent. Chinese companies are at the leading edge of developing AI-enabled predictive policing and large-scale surveillance technologies. China also is championing concepts such as Internet sovereignty, and relatedly, implementing policies to control cross-border data flows. Cumulatively, these actions and ideas are providing support to authoritarian-leaning leaders around the world who fear feedback from their citizens and criticism from abroad, and who seek tools to maintain their grip on power.

In other words, there are serious causes for concern about the effects of China’s actions. Countries around the world should be pressing China on these issues, for example, by urging China to respect environmental, labor, and social safeguards and ensure debt sustainability for projects it funds overseas. Countries also should be competing in the battleground of ideas over the benefits of an open, secure, reliable, and interoperable cyberspace environment versus a balkanized one. And there should be an active international dialogue over the ethical boundaries on uses of artificial intelligence technologies as it relates to international conventions on human rights.

This is where attention should be focused — on addressing concrete concerns about specific problems. If the United States leads by example and rallies other democracies with it, it could greatly strengthen its influence and its ability to push back on problematic Chinese behavior.

If, on the other hand, policymakers choose to use broad ideological brushes to paint the challenges emanating from China, they will be less likely to find an audience for their concerns in China, and less able to attract international support for raising them with Beijing.

Cold War analogies for describing U.S.-China relations are appealing for their simplicity and clarity. But they are misleading and counterproductive for dealing with the real challenges that China’s actions pose to good governance around the world.

Commentary

Op-edIs the Cold War coming back? Not quite

Monday, November 5, 2018