Discussions of criminal justice reforms often focus on lowering the number of individuals sentenced to prison or shortening prison sentences. What these discussions sometimes miss are the many ways in which punishments continue long after an individual is released from prison—a practice that is actually counterproductive, harming public safety, the well-being of former offenders and their families, and the labor market.

For the United States, fixing these counterproductive policies could have large benefits due to the sheer scale of criminal punishment. About 2.25 million of Americans are currently incarcerated which is five times higher than the average rate among developed nations. And the number has risen dramatically: in 1980, only 500,000 people were incarcerated – we now have almost five times as many people in jail and prison as we did back then.

Even these high incarceration rates understate the full reach of our criminal justice system. Including those on probation or parole, nearly 7 million Americans are under criminal justice supervision – more than 2 percent of the U.S. population. As these individuals leave supervision, they join an even larger pool of Americans with felony convictions on their records, estimated by some at 14 to 15.8 million.

Although these citizens have served their time, their punishment continues long after they leave prison, and is counterproductive. They continue to face what are called the “collateral consequences” of criminal conviction long after they cease to pose a risk to public safety.

An underappreciated fact about criminal recidivism is that it is much more common immediately after release from prison, among young people, and for those with multiple prior convictions. Once one or two years have passed uneventfully since release from prison, the probability of re-offending drops considerably. Nonetheless, substantial collateral consequences related to employment, income support, and civic participation persist in the lives of people with criminal records.

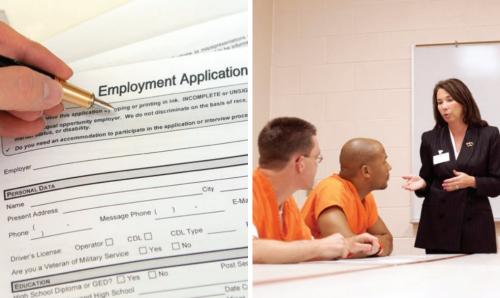

In a recent Hamilton Project paper, Professor Anne Piehl of Rutgers University outlines the problems of long-term collateral consequences and suggests strategies for addressing them. One of the most counterproductive collateral consequences relates to occupational licensing, which prevents many of those with criminal records, even records that are decades old, from accessing gainful employment. Notably, this government action is not a part of the official sentence meted out to an offender. Rather, it is the product of occupational licensing regulations, often implemented with a great deal of discretion by licensing boards, that bar or revoke an individual’s right to work based on criminal records that may have little or no relevance to the license sought.

In some instances, it may be appropriate to refuse to license an individual with a criminal record – think of someone with a DUI applying for a commercial driver’s license. But in many other instances, a record is irrelevant to the sort of work an individual would like to do. For example, applicants for Massachusetts licensure as sheet metal workers can be denied on the basis of any misdemeanor or felony. Denial of licensure in these situations serves only to decrease the chances that people with criminal records find legitimate employment. Given that employment is a predictor of success at avoiding relapse into crime, this becomes a problem for public safety. To fix this problem, states should enact laws (as some already have) that limit occupational licensing restrictions to cases in which they are clearly justified.

The collateral consequences of criminal conviction extend beyond occupational licensing restrictions, of course. Many states ban people with felony convictions from accessing the social safety net (primarily food stamps and cash welfare), and a number of states continue to prohibit the same individuals from voting. A recent Hamilton Project background paper depicts the range of limitations imposed on those with criminal records. In distinct ways, these limitations all constitute impediments to full participation in civic and economic life.

As Professor Piehl argues, policy makers should look for systematic ways to minimize counterproductive collateral consequences. The guiding principle is that any collateral consequences should be carefully targeted to enhance public safety. This will prevent irrelevant licensing restrictions and ease the burdens placed on those with criminal convictions from the distant past. In addition, policy makers should establish processes to time-limit information about convictions. When an individual with an old conviction record is able to expunge or seal that record, a variety of collateral consequences are eliminated at once. Indeed, states are already taking action: Missouri recently extended its use of expungement for those with sufficiently old conviction records.

In some areas, painful trade-offs between the objectives of public safety, the well-being of people with criminal records, and controlling incarceration costs may be unavoidable. There, arguments over appropriate criminal justice policy will require difficult empirical and moral judgments. But for the array of counterproductive policies that our nation currently implements, it is past time to make changes that enhance public safety, save money, and improve the lives of people with criminal records.

Commentary

Op-edExcessive regulations get in the way of work and second chances

November 18, 2016