For last year’s words belong to last year’s language and next year’s words await another voice, and to make an end is to make a beginning. – T.S. Eliot

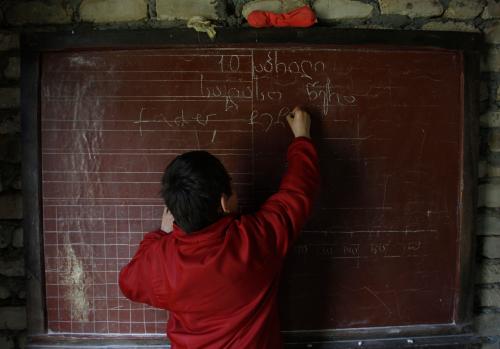

The year 2013 was a year of much discussion about learning. While conversations in years past often focused only on attending school, global events throughout 2013—post-2015 agenda consultations, Learning for All Ministerial meetings and the Global Education First Anniversary—focused on the more important question of how much knowledge students are actually gaining while in class. The essential discussion at these global events have put learning and the quality of education at center stage, spurred on by chilling estimates that 250 million children are not learning, even though many of them have spent time in school.

It makes sense to invest in the quality of education. A number of reports in 2013 have convincingly argued (and confirmed earlier research) that investing in quality education does not just transform individual lives, but helps achieve all development goals. Recent analysis by the Education For All Global Monitoring (EFA GMR) report shows that, if all mothers had a secondary education, physical stunting could be reduced by 26 percent and fertility rates would be cut by half, contributing tremendously toward healthy lives and family sizes that could be better cared for. Education also makes our planet safer and more sustainable. Education promotes tolerance and trust and people with more education have been found to care more about the environment. Others have highlighted that investing in education also makes business sense. Each dollar invested in education today by a typical Indian company returns more than $50 in value to the employer at the start of a person’s working years.

It will take time to move the needle but the collective knowledge about learning gathered in 2013 provides a strong basis for action in 2014. Four lessons stand out.

Let’s Measure What We Treasure

We cannot improve education outcomes without first being able to measure them. The United Nations’ high-level panel report on the post-2015 development agenda called for a data revolution to improve the quality of statistics and information available to citizens. In education this means improving the measurement and monitoring of learning, in addition to access. However, little is known about what children are learning in most developing countries. Less than 60 percent of all developing countries have national learning assessments and no international assessment covers more than half of those countries. Thanks to the Learning Metrics Task Force a consensus is emerging around global learning indicators and actions to improve the measurement of learning in all countries. Putting these recommendations into action will be the challenge for the coming year. This will require getting parents, communities and governments excited not only about getting children into school but also about what they are learning and how it is measured. The private sector can also play an important role. They can join efforts to develop appropriate assessment tools through initiatives such as the PISA for Development Initiative launched this year or support the development of technologies to collect and disseminate learning data. The predicted expansion of “leapfrog” technologies could also benefit the measurement and monitoring of education outcomes.

Equity is Key

In addition to measuring access and learning outcomes, improving education outcomes will require reviewing who gets what. Financing systems will need to be reformed to counteract existing inequalities. This is relevant for developed as well as developing countries. Recent studies have shown that countries that have adopted financing formulas that equalize the tax base and provide adequate funding for all districts, not just the wealthy ones, have tended to outperform others on the international PISA test (Canada is an example). In fact, the equitable allocation of funding may be more important than total spending in improving educational outcomes, which highlights the importance of establishing appropriate financial systems in nascent education systems in the developing world. (Here at Brookings, this topic is part of an ongoing work program on equitable finance at the Center for Universal Education (CUE). Findings will be presented at CUE’s annual symposium on February 24 and 25, 2014.)

Luckily, the “leave no-one behind” agenda has been at the core of development discussions this year and there is room for education to play an important role in putting this ambition into action. Equity targets in education have also been highlighted as fruitful stepping stones towards broader post-2015 equity goals that would be more difficult to address head-on, such as those related to income or wealth. Indeed, the EFA GMR estimates that over a forty-year period income per capita is 23 percent higher in countries with more equal education.

It can be done! It’s No Time to Scale Back Support.

Two striking facts should be driving those who choose where money is spent. First, done right, spending on education has fabulous returns. Second, it does not require huge resources to address the problem. After taking account of available domestic and donor resources, it is estimated that an additional $26 billion per year will be needed to make sure all the world’s children receive a quality basic education by 2015 (that is less than 4 percent of the U.S. defense budget). But some reports this year have highlighted that international support may be waning. Multilateral organizations have made education a lower spending priority. Private contributions are also falling short, amounting to just 5 percent of total aid from donor countries on the Development Assistance Committee of the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD-DAC), a group of high-income states. A recent report by the Global Partnership for Education highlights a 16 percent decline in external aid for education in 2011 for its 58 low-income partner countries compounding an already challenging fiscal environment in many of these low-income countries. And while many countries have increased the share of funds put toward education in domestic public spending, many still fall short of the recommended 20 percent.

Efforts to scale optimal financing of education will also have to tackle the abysmal lack of financing data in education, and the lack of transparency and accountability in education spending. This year’s Global Corruption Report on education highlights huge financial losses due to misappropriation in education, amounting to $21 million over two years in Nigeria and double that amount in Kenya over five years.

Dynamic Systems—Not Blueprints—Are Needed

The Learning for All Ministerial meetings held in April and September 2013 highlighted that solutions to achieve proper learning outcomes for all are highly contextual, and attention will need to be paid to the political dynamics. While challenges in countries that participated in the Ministerial seemed remarkably similar, proposed solutions varied significantly. A summary of these solutions in 10 countries with the largest out-of-school populations will be presented in a series of blogs in the coming weeks. Lant Pritchett’s insightful new book underlines the need for a “Rebirth in Education” with fewer top-down, pre-determined “spider” system models and more open, flexibly-financed, locally-driven “starfish” systems. Successful systems will have common principles but lots of different methods for implementation. For example, Pritchett finds that financing systems can take different forms as long as resources are “flowing naturally into those schools and activities within schools that have proved to be effective”. The Center for Universal Education’s Millions Learning project, to be launched early 2014, will be examining those principles of successful scaling of learning in a number of developing countries. A better understanding of how to achieve learning goals will be important as the world gets ready to implement the post-2015 development agenda.

We have talked and learnt much about learning in 2013. Let’s hope 2014 is indeed a new beginning to put words and wisdom into action.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).

Commentary

Learning about Learning in 2013: An Agenda for Action in 2014

January 7, 2014