Editor’s note: This post originally appeared on the Health Affairs Blog on May 7, 2015. Click here to view the original.

Although many commentators have criticized the underfunding of public pension plans, relatively few have focused on the huge underfunding of retiree health care plans of states and cities. At the time of Detroit’s bankruptcy, for example, its pension plan was underfunded by over $3 billion, but the unfunded deficit in its retiree health care plan was close to $6 billion.

The good news is that retiree health care plans can legally be revised more easily than pension plans. In specific, the US Supreme Court has recently issued an opinionsetting forth principles of contract interpretation that will lead local governments and public unions to reach explicit agreements on the scope of such plans. Those agreements will probably have to include some cost reductions because the health care plans of many local governments will otherwise be subject to the Affordable Care Act’s 40 percent “Cadillac” tax starting in 2018.

This post will be divided into four parts. It will explain

- the reasons why retiree health care plans have stayed under the radar screen and how that is changing;

- the magnitude of underfunding of retiree health care plans and the implications for state-city budgets;

- the principles of interpreting collective bargaining agreements recently enunciated by the US Supreme Court; and

- the various ways local governments are now trying to manage down their health care obligations over time and strategies that governments and public-sector unions can use to address this challenge.

Staying Below The Radar Screen

Approximately 77 percent of all local governments pay most of the health care premiums for their retirees from the time they retire (often before age 55) until they join Medicare at age 65. Then many local governments continue to pay most of the Medicare premiums for their retirees, and sometimes their premiums for supplemental health insurance (e.g., Medigap). These retiree health care plans are quite costly for local governments. The plans generally offer a broad range of high-quality services, including dental and eye care, with small or no deductibles and co-payments.

Before 2006, however, local governments were not required by the Government Accounting Standards Board (GASB) to publicly disclose their other postemployment benefits” (OPEBs) — composed almost entirely of health care benefits. So it was easy for politicians to approve generous health care plans whose financial effects would not be felt for decades, when those politicians were no longer in office.

Last year GASB proposed to tighten the rules on OPEBs in two key respects. First, it proposed to establish a uniform discount rate for calculating unfunded health care obligations at a level significantly lower than the rate currently utilized by most local governments. A discount rate is applied to reduce long-term liabilities by taking into account the relatively certain investment returns on a plans’ assets, which help finance future benefit payments. Accordingly, a lower discount rate would mean higher unfunded liabilities for retiree health care plans.

GASB also proposed that local governments go beyond the public disclosures required since 2006—in the footnotes to their financial statements—by showing their projected health care obligations as liabilities on their balance sheets. This accounting change would emphasize the financial impact of these unfunded health care obligations, hopefully leading to more attention from local voters and bond rating agencies.

Nevertheless, even GASB has NOT proposed that local governments set aside monies to help finance their future health care obligations, as states and cities usually do for pension obligations. A discount rate is applied to reduce long-term liabilities by taking into account the relatively certain investment returns on plans assets, which help finance future benefit payments. By contrast, state and city governments have on average pre-funded less than 5 percent of their retiree health care obligations; these obligations are typically paid out of current tax revenues.

Scope Of Unfunded Retiree Health Care Obligations

The overall size of the OPEB liabilities of local governments is huge and rising rapidly. In 2009, the General Accounting Office estimated that these liabilities were more than $670 billion. A more recent and comprehensive estimate in the Journal of Health Economics estimated OPEB liabilities of local governments at close to $1 trillion dollars. However, the size of these OPEB liabilities varies widely among states and cities in the United States.

As shown by Chart I, New Jersey has the highest OPEB liabilities per capita of the states, at $7,206 per capita. On the other hand, Chart I shows that several states have low levels of OPEB liabilities per capita — with Idaho the lowest at $53 per capita. These states with low OPEB liabilities per capita have relatively weak public unions and relatively strong fiscal discipline.

Chart I

Source: Standards & Poor’s Rating Services “U.S. State OPEB Liabilities Decline Slightly, But Continue To Vary Widely”

Similarly, as shown by Chart II, there are tremendous differences in unfunded OPEBs among the 30 largest cities in the US. New York City leads the pack by both total amount of OPEB liabilities and OPEB liabilities per household — partly because its OPEB statistics include the retiree health care obligations to the City’s teachers. Conversely, Denver, Minneapolis, and Tampa have kept their OPEB liabilities below $90 million in total amount and $620 per household.

Chart II

Source: The Pew Charitable Trusts: American Cities

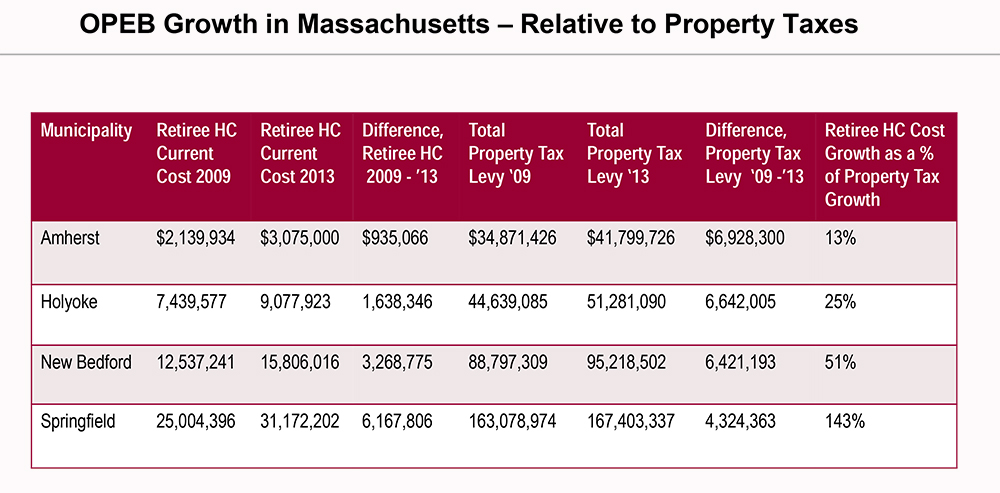

In states and cities with large OPEB liabilities, there is almost no advance funding, so these health care benefits are paid out of current tax revenues. As health care benefits grow, they compete for tax dollars with essential services like schools and police. Consider Chart III, which compares health care spending with property tax revenues in four Massachusetts cities. In all four cities, retiree health care spending and local property taxes increased substantially from 2009 to 2013; yet health care spending grew faster than property tax revenues so that such spending consumed a growing percentage of rising property taxes.

Chart III

Source: Massachusetts Taxpayers Foundation

New Legal Guidance From The US Supreme Court

Given the growing unfunded liabilities for retiree health care and their rising conflicts with other public spending priorities, many states and cities have recently tried to manage down these liabilities. However, local governments will face lawsuits by the unions representing public employees in response to any proposal to pare back benefits. In the pension arena, public unions have won almost all these suits because courts have held that most pension benefits are protected explicitly or implicitly by the state’s constitution — which is almost impossible to change.

By contrast, the legal status of health care plans has been more subject to debate. State constitutions do not usually address protections for retiree health care plans. These plans are also exempt from the federal pension protections in ERISA, the federal law governing employee retirement benefits. Moreover, most retiree health care plans have minimal advance funding, so the beneficiaries of such plans are legally unsecured creditors of the relevant public entity. In Stockton, California, for instance, the judge approved the city’s bankruptcy plan, which totally eliminated health care benefits of public retirees while preserving most of their accrued pension benefits.

For solvent local governments, the legal status of retiree health care plans is primarily determined by the collective bargaining agreement with the relevant union.

Earlier this year the US Supreme Court announced principles of contract interpretation that will help local governments defeat court challenges to future reductions in retiree health care benefits. M&G Polymers vs. Tackett addressed a collective bargaining agreement that provided certain retirees with “a full Company contribution” of their health care benefits “for the duration of [the] Agreement.” When the company asked retirees to start contributing some of their health care premiums, the union sued on the theory that the company had created a vested right in their employees to free lifetime health care.

The union prevailed in the Court of Appeals, which was reversed by a unanimous Supreme Court. Although the case took place in the private sector, the principles should generally apply to public sector agreements on retiree health care benefits.

The Supreme Court began by finding that the express language of the collective bargaining agreement was ambiguous on the question of how long health care benefits would be paid in full by the company. Given that ambiguity, the Supreme Court opined that judges should look for hard evidence of what the parties actually intended, rather than making their own inferences about contractual intent.

The Supreme Court went on to articulate two interpretive principles that will be especially relevant to collective bargaining agreements on health care benefits, which often are unclear on the duration of those benefits. The Supreme Court supported the “traditional principle that courts should not construe ambiguous writings to create lifetime promises.” Instead, the Supreme Court endorsed the principle that “contractual obligations will cease, in the ordinary course, upon termination of the bargaining agreement.”

Potential Reforms To Retiree Health Care Plans

With this guidance from the Supreme Court, states and cities are likely to negotiate express modifications to their retiree health care plans as their collective bargaining contracts expire. It should be relatively easy to agree to premium contributions by retirees or less generous post-retiree benefits if these changes are applied only to newly hired public employees. However, such changes will take decades to have a material financial impact.

On the other hand, it will be politically difficult to reduce the health care benefit package of public employees who have already retired. They presumably stayed in their public jobs in part because they expected to receive certain health care benefits after retirement. Nevertheless, the Supreme Court’s decision would legally allow cities and states to renegotiate the health care package provided to already retired employees — unless the applicable collective bargaining agreement expressly extended that package for the life of such employees. Similarly, the Supreme Court’s decision would legally allow cities and states to renegotiate the post-retirement health care package for current employees after the termination of the current collective bargaining agreement — unless the prior agreement expressly extended the duration of the package.

In these negotiations, local governments and their unions should discuss possible reforms, such as:

- Lower limits on cost of living adjustments (COLAs), which sometimes exceed the inflation index.

- Partial payment of health care premiums by retirees, especially the premiums charged by Medicare.

- Stricter eligibility rules in terms of years of public employment to obtain full health care benefits.

- Required sign-up for health care coverage offered by a private employer if a retiree gets a job in the private sector.

- Co-payments and deductibles for prescription drugs and doctors’ visits (except for preventive care).

- Narrower scope of medical services or separate charges for eye glasses and dental work.

Of course, public employee unions will resist most of these changes, but they may be necessary for many local governments to avoid the “Cadillac” tax beginning in 2018. This levy is a 40 percent excise tax on the annual costs of a health care plan above $10,200 for an individual and $27,500 for a family.

Although precise cost figures are not readily available, many health care plans in the public sector will clearly have to pay the 40 percent Cadillac tax under their current trajectories. For example, the New York deputy mayor estimated that the Cadillac tax would cost his city $22 million in 2018 and $549 million in 2022. Similarly, the association providing a pooled health care plan to municipalities in Washington State estimated that the Cadillac tax could add $76 million in local taxes over the decade starting in 2018— unless health care costs are constrained.

In short, the Supreme Court’s recent decision will lead to the renegotiation of health care benefits at the expiration of the current collective bargaining agreement in most states and cities. In these negotiations, the threat of a Cadillac tax will lead local governments to propose health care plans with more employee contributions and less generous benefits. In response, public unions should not accept these proposals unless local governments commit to a binding schedule to advance fund the revised health care plans. Without assets backing these plans, public retirees have little assurance they will actually receive the promised healthcare benefits in the future.

Commentary

Renegotiating retiree health care plans after new supreme court guidance

May 7, 2015