What’s the latest thinking in fiscal and monetary policy? The Hutchins Roundup keeps you informed of the latest research, charts, and speeches. Want to receive the Hutchins Roundup as an email? Sign up here to get it in your inbox every Thursday.

Upcoming webinar: The 11th annual Municipal Finance Conference will be held July 18-20, 2022, as a virtual event. Visit this page for more information, including agenda and registration, and email Stephanie Cencula ([email protected]) with any questions.

Demand spike likely responsible for rising housing prices during pandemic

Using a model of the housing market and data on listings and sales, Elliot Anenberg and Daniel Ringo of the Federal Reserve Board find that housing demand explained essentially all of the variation in home sales and 80 percent of the variation in home prices between 2002 to 2021. During the pandemic, house prices increased because of a surge in demand that would have required a 30 percent increase in listings to maintain pre-pandemic prices, representing a 300 percent increase in new construction. This suggests that policies to reduce bottlenecks to new construction would have done little to cool the pandemic housing market because, even under ideal conditions, construction could not have increased by nearly this much. The authors also show that housing demand is more sensitive to interest rates than previously estimated, with a 1 percentage point increase in mortgage rates reducing demand by 10.4 percent, suggesting that policies that target mortgage rates are an effective way to influence the housing market in the short run.

Increase in institutional ownership reduces firms’ employment and payroll

Using establishment-level data from the Census Bureau’s Longitudinal Business Database, Antonio Falato of the Federal Reserve Board and co-authors find that increased concentrations of institutional ownership reduce employment and payroll. Specifically, the authors find that a 10 percentage point increase in large institutional ownership is associated with between a 2.1 percent to 2.5 percent reduction in a firm’s employment and payroll. Furthermore, higher levels of institutional ownership are associated with higher shareholder returns but no improvements in productivity, suggesting a reallocation of resources from workers to shareholders. Based on estimates from the microdata, the authors estimate that the rise in concentrated institutional ownership could explain about one-quarter of the decline in the share of national income going to labor.

Politicization of the ACA may have increased costs

Republicans were 8.0 percent less likely, on average, than Democrats to purchase health insurance from Affordable Care Act marketplaces, with healthy Republicans 12.9 percent less likely to purchase coverage than equivalently healthy Democrats, find Leonardo Bursztyn of the University of Chicago and coauthors. The authors link individual-level survey data from the Kaiser Family Foundation Health Tracking Poll from 2014-2019 to cost data from the Medical Expenditure Panel Survey. They find that this “political adverse selection” of healthy Republicans out of the program increased average per capita costs in ACA marketplaces by 2.7 percent. As a result, government spending on low-income subsidies increased by $105 per enrollee, with larger increases in more heavily Republican regions.

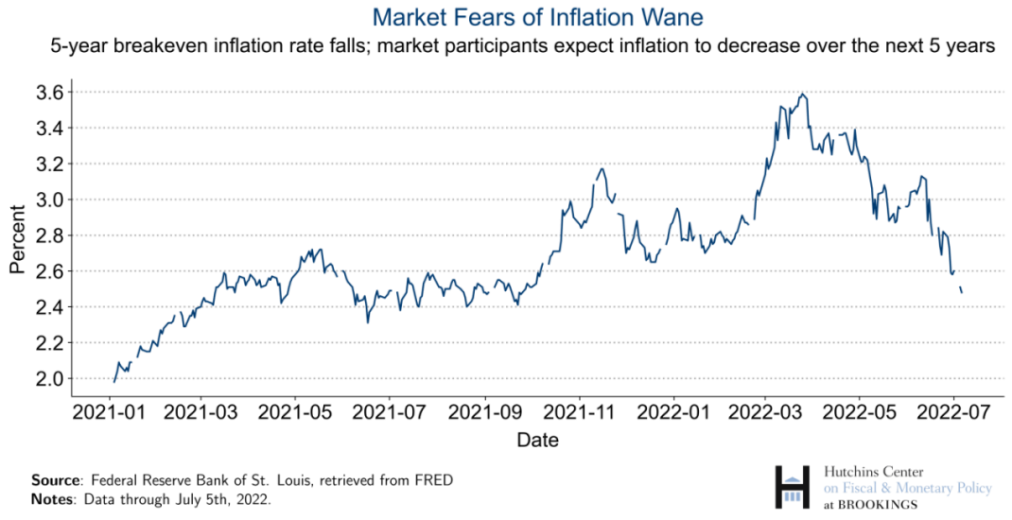

CHART OF THE WEEK: Market Fears of Inflation Wane

Chart data courtesy of the Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis

Quote of the week:

“In the current situation, from a risk-management perspective, it is important for policymakers to ask which situation would be more costly: erroneously assuming longer-term inflation expectations are well anchored at the level consistent with price stability when, in fact, they are not? Or erroneously assuming that they are moving with economic conditions when they are actually anchored? Simulations of the Board’s FRB/US model suggest that the more costly error is assuming inflation expectations are anchored when they are not.” says Loretta J. Mester, president of the Federal Reserve Bank of Cleveland.

“If inflation expectations are drifting up and policymakers treat them as stable, policy will be set too loose. Inflation would then move up and this would be reinforced by increasing inflation expectations. If, on the other hand, inflation expectations are actually stable and policymakers view the drift up with concern, policy will initially be set tighter than it should. Inflation would move down, perhaps even below target, but not for long, since inflation expectations are anchored at the goal.”

The Brookings Institution is financed through the support of a diverse array of foundations, corporations, governments, individuals, as well as an endowment. A list of donors can be found in our annual reports published online here. The findings, interpretations, and conclusions in this report are solely those of its author(s) and are not influenced by any donation.

Commentary

Hutchins Roundup: Housing prices, institutional ownership, and more

July 7, 2022