Content from the Brookings Doha Center is now archived. In September 2021, after 14 years of impactful partnership, Brookings and the Brookings Doha Center announced that they were ending their affiliation. The Brookings Doha Center is now the Middle East Council on Global Affairs, a separate public policy institution based in Qatar.

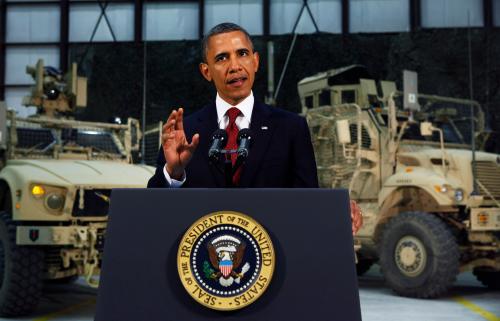

Barack Obama’s victory in Tuesday’s Presidential election gives him a second chance to attempt to bend history the way that he had wanted to do after his first election. He will have to give priority to addressing economic issues—particularly the fiscal crisis. And he will inevitably have to devote time and energy to bridging the great political divide on domestic issues. Nevertheless, he will want to burnish his foreign policy legacy and he may well have greater opportunity to make history abroad than at home. Many foreign policy issues have been placed on the back-burner while the president focused on his reelection bid, and some will now command priority attention: Iran is still advancing towards a nuclear weapons breakout capability; Syria is descending into sectarian warfare that threatens to spread to Lebanon, Iraq and Bahrain; the Palestinians are threatening a UN General Assembly vote that could force a cut-off in U.S. funding to the United Nations; China’s new leadership may find it necessary to assert itself abroad to deal with domestic pressures; the ongoing Eurozone crisis threatens the global economic recovery; and Russia is expecting to negotiate a new strategic arms control agreement.

In particular, Obama will need to decide quickly how to test Iran’s willingness to negotiate an agreement that will curb its nuclear weapons aspirations. He will need to consider whether to take the lead in attempting to shape a post-Assad order in Syria, in particular by arming the opposition. He will need to flesh out his strategy for “pivoting” to Asia in ways that encourage cooperation between the United States and the two rising Asian powers—China and India. And he will have to consider the pace and manner in which he ends the war in Afghanistan. In these and other ways he will have the opportunity to shape the emerging global order in directions that preserve American strategic interests and promote American liberal values.

Overall, this is a moment for the Obama Administration to look at ongoing challenges with fresh eyes. In the following pieces, Foreign Policy at Brookings’ leading experts examine a number of challenges and opportunities that await the president as he prepares for the final four years of his presidency. Tamara Wittes outlines four challenges facing the next U.S. administration in dealing with the Arab Awakening. Shadi Hamid argues that the Obama presidency was characterized by a lost faith in America’s ability to impact the course of events in the Middle East. Suzanne Maloney looks at the prospect of renewed diplomacy with Iran, in the wake of President Obama’s reelection. Daniel Byman examines why implementing policy in Libya or other Arab countries with new political realities will be far harder if Americans are not on the ground.

Supporting Arab Transitions: Four Challenges for the Next U.S. President

Supporting Arab Transitions: Four Challenges for the Next U.S. President

Tamara Cofman Wittes, Director and Senior Fellow, Saban Center for Middle East Policy

Americans are notoriously inward-looking when it comes to electing presidents. Except for rhetorical flourishes (who is tougher on China or Iran, who is closer to Israel), foreign policy did not feature much in the election campaign. When the candidates debated foreign policy, they agreed more than they disagreed. The American electorate still suffers the effects of a lagging economy, and poll after polls throughout our long presidential campaign has demonstrated the American public’s desire to disengage more from foreign entanglements and focus on “nation-building here at home.” Indeed, these sentiments helped bring President Obama into office four years ago, and they have only strengthened since.

And yet, as a global power with global interests, America can not afford simply to disengage from world affairs — and other nations seek incessantly to draw the United States in. Even when when a new president takes office determined to focus on domestic affairs, foreign policy has a way of forcing itself onto his agenda.

Middle East Lost

Middle East Lost

Shadi Hamid, Director of Research, Brookings Doha Center and Fellow, Saban Center for Middle East Policy

One of the great mysteries of the past four years is how Barack Obama—who rose to the presidency, in part, on his promises to fundamentally re-think and re-orient U.S. policy in the Middle East—has instead spent his term running away from the region.

It is difficult to remember it now, but the prospect of an Obama presidency was initially greeted in the Arab world with a mixture of relief and guarded optimism. His name and Muslim origins certainly helped. But there was something else: For the first time, here was an American president who seemed to have an intuitive grasp of Arab grievances. This grasp extended, perhaps most importantly, to the Arab-Israeli conflict. Israelis may have been victims, but so too were the Palestinians. In short, Obama seemed to “get” the Middle East. This didn’t sound like someone who wanted to spend three years “pivoting” to China.

Make-or-Break for the U.S. and Iran

Make-or-Break for the U.S. and Iran

Suzanne Maloney, Senior Fellow, Saban Center for Middle East Policy

It is an accident of fate that the quadrennial American exercise in selecting a president happens to coincide almost precisely with the anniversary of the 1979 seizure of the U.S. Embassy in Tehran. That episode unraveled the Carter Administration and left a legacy of U.S.-Iranian animosity that has confounded every subsequent America president. And so it was last week, on the eve of Barack Obama’s historic reelection victory, that thousands of Iranians joined in the Islamic Republic’s commemoration of the hostage ordeal, which has become an annual jubilee of anti-Americanism, with demonstrators showcasing effigies of Obama and shouting ‘death to America.’

Such scenes, together with the bombastic rhetoric of Iranian leaders who used the anniversary to vilify Washington as “the most criminal regime on earth,” might suggest that little has changed between the two old adversaries and that the prospects of any progress in resolving the crisis over Iran’s nuclear ambitions remain as distant as ever. However, as is often the case with Iran, the reality is more complex than the rhetoric. In fact, both sides have been signaling readiness to jumpstart diplomacy in the aftermath of President Obama’s reelection, with press reports focused on the contours of preliminary concessions from each side circulating even before Americans went to the polls.

A Less Nimble America in the Arab World

A Less Nimble America in the Arab World

Daniel Byman, Deputy Director and Senior Fellow, Saban Center for Middle East Policy

This was not a foreign policy election. Indeed, in contrast to past campaigns, the Republican candidate was not able to successfully assert that he would better protect America. President Barack Obama used his administration’s killing of Osama bin Laden as a way of making security a non-issue. So despite the presence of over 60,000 American troops in Afghanistan, the implosion of Syria and Iran’s nuclear ambitions, the only foreign policy issue that made a dent during weeks before election day was the killing of American Ambassador Chris Stevens and three other Americans in Benghazi, Libya. Even this tragedy only led to a debate about blame, not about shifting the course of U.S. foreign policy.

However, the killing of Ambassador Stevens — or more accurately the U.S. reaction to it — is likely to make one of the biggest challenges facing the second Obama administration even bigger: what to do about the Arab spring? To put it mildly, the United States has had an inconsistent response to the Arab spring. Libya saw decisive military intervention, while in Egypt the Obama administration impressively helped usher Mubarak from power. More quietly, the United States worked with its allies to give Yemen’s Saleh a push. In Bahrain, however, the Obama administration did little while the government brutally repressed demonstrations. And in Syria, Washington has only slowly moved to back the Syrian opposition, and even then it is maintaining a healthy distance.

Commentary

Foreign Policy and the 2012 Presidential Election

November 8, 2012