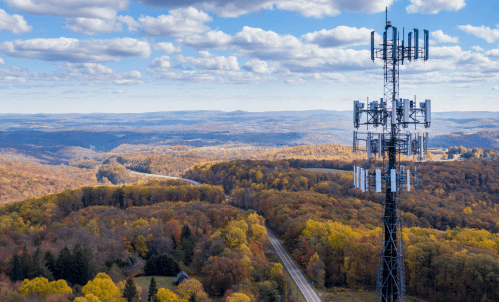

In his most recent State of the Union address, President Joe Biden highlighted the $42.5 billion Broadband Equity, Access, and Deployment (BEAD) Program for connecting unserved and underserved locations to broadband. Part of the 2021 Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act, Biden boasted that the program would connect everyone: “We’re making sure that every community has access to affordable, high-speed internet.”

However, in the same address, Biden went on to declare that “when we do these projects, we’re going to buy American…Tonight, I’m also announcing new standards to require all construction materials used in federal infrastructure projects to be made in America.”

The problem is that the country can close the rural digital divide in the next few years, or it can enforce a strict Buy American mandate. It cannot do both—requiring the administration to decide which principle it wants to prioritize over the other.

Biden’s declaration kicked off an administrative process designed to address how the Buy American policy applies to government-funded broadband networks. The day after the State of the Union, the National Telecommunications and Information Administration (NTIA)—the agency charged with distributing broadband deployment dollars—wrote, “The president made clear that while Buy America has been the law of the land since 1933, too many administrations have found ways to skirt its requirements. We will not.” The Office of Management and Budget (OMB) also began a process “to clarify existing requirements” and “provide further guidance on implementing these statutory requirements.”

The question the Biden administration must address is whether the Buy American requirements apply to 100% of the materials used in construction of a BEAD-funded broadband network, or whether it can be waived for specific components not currently produced in the United States.

In examining that issue, the administration should consider three fundamental realities.

First, no matter what it decides, more than 90% of the total cost of broadband construction will go to American labor and materials. Seventy percent will go to labor, and of the remaining 30% of construction costs, 70% will be spent on the fiber conduit, for which there is an existing American supply.

Second, there are many critical elements of broadband networks that, while representing less than 10% of the budget, are essential and cannot in the near term be sourced from American manufacturers. As the NTIA already discovered in analyzing the Buy American implications for its Middle Mile Grant Program, certain critical components (including “broadband switching equipment, broadband routing equipment, dense wave division multiplexing transport equipment, and broadband access equipment”) are “sourced exclusively from Asia.” The NTIA study also indicated that there is a shortage of some types of American-made semiconductors and broadband components.

Third, if the Buy American requirements are enforced for all the components necessary to deploy and operate the networks, it will cause significant delays in deploying broadband networks everywhere. Those deploying the networks would have to halt their current plans until they convince enterprises capable of manufacturing those components to do so in the United States. It is not clear those enterprises would do so, given the one-time nature of the federal government spending on broadband deployment.

This would mean further delays until new facilities are constructed and start to produce a sufficient supply of components (and those components go through a rigorous testing process). “Domestic manufacturing capacity for components, broadband routing and broadband transport equipment will require, at minimum, 24-36 months,” the NTIA study noted.

In its filing to the OMB, the Information Technology and Innovation Foundation summarized the situation this way: Requiring all components to be manufactured in the United States “would be gambling BEAD funds on successful negotiations with foreign manufacturers, successful construction of sufficient manufacturing capacity, and successful sustaining of that capacity throughout the construction of BEAD projects. All three gambles are highly uncertain and unnecessary.”

Adding to the complexity of negotiating the necessary contracts, by the time manufacturing facilities are built and producing components, the economics of deploying networks will have been negatively altered. Over the past year, internet service providers (ISPs) and all 50 states have spent significant capital setting up the functions necessary to award BEAD funding and start constructing networks in the next 12 months. If the process is delayed by several years, we don’t know if states will still have the personnel devoted to the effort. Further, greater inroads in rural markets by fixed wireless broadband and satellite ISPs will make those markets less attractive to fiber-based service providers, therefore increasing the capital funding caps that BEAD needs to cover.

In short, if Buy American requirements delay BEAD-funded deployments, the costs to deploy networks will be higher and the expected market returns will be lower—resulting in the BEAD dollars reaching fewer unconnected Americans.

This is not a new problem. As an industry coalition noted in a letter to the NTIA, “Although the 2009 American Recovery and Reinvestment Act (ARRA) imposed identical requirements, NTIA and the Department of Agriculture’s Rural Utilities Service determined that a waiver for broadband equipment was necessary to effectively implement the legislation.”

There are solutions that would honor the aspirations of both the Buy American policy and the infrastructure law’s broadband provisions. The simplest way would be for the OMB or NTIA to issue a waiver for all BEAD project components except fiber optic and copper cable. That is essentially what the Obama administration did for the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act’s broadband funding program. There could also be more targeted waivers for specific components.

There is a need for speed. The NTIA will finalize funding allocations to states by June 30, and states will finalize their plans by the year’s end. The ISPs who will bid for the funds are already deep in the planning process. If there are not clear signals on Buy American requirements and waivers, the whole process will grind to a halt. Plans for thousands of American construction and installation jobs would be jettisoned, millions of Americans would remain disconnected, and the potential for economic growth and job creation in unconnected areas would be unrealized.

President Biden is on solid ground in contending that bringing broadband to all communities would constitute an historic achievement for his administration and America. But inflexibility on Buy American provisions could put this once-in-a-generation opportunity at risk of failure.

Commentary

Biden’s ‘Buy American’ policy could put broadband deployments at risk

April 20, 2023