One of the difficulties with studying intergenerational social mobility is that it takes a long time for the data to come in: at least a generation, in fact. A constant dilemma faces scholars in the field. Newer data is, by definition, a closer fit to current social and economic realities – but can tell us little about long-run outcomes. Older data gives us a longer time frame, but may tell us little about whether the patterns of the past are the patterns of the present – let alone the future.

Social Mobility Stats: All About the Boomers

Studies of intergenerational social mobility typically rely on estimates of how a person’s adult income at around age 35-45 can be predicted by their childhood circumstances. So, we use data on people born between 1950 and 1970. It is important to remember that most studies of social mobility are not describing Millennials or even Gen Xers – they’re describing Baby Boomers.

Old Data Makes Race and Mobility Hard to Study

Of course, it may be that nothing significant has changed in society or the economy over this time period, in which case the backdated nature of the analysis won’t matter. But if there have been big changes, we might see a big difference in the mobility patterns of Boomers and Millennials, for instance.

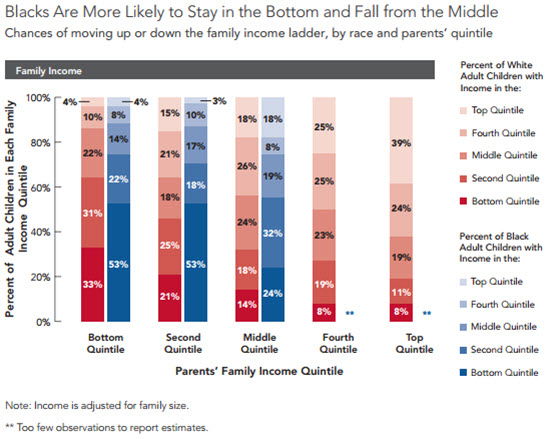

Race is a case in point. Studies consistently find that Black Americans have less economic mobility:

Source: Pew,

Pursuing the American Dream: Economic Mobility Across Generations

But these estimates are for Americans growing up in a quite different era, in terms of race, civil rights, and segregation.

School Desegregation and Black Mobility

Many school districts, particularly in the South, did not fully comply with desegregation for many years after the 1954 Brown vs Board of Education ruling. One district in Alabama, highlighted in a new Atlantic article, did not fully integrate until 1979.

Many black children of school age in the 1960s and 1970s were receiving a very different educational experience compared to Black children in later years.

So there is reason to hope that the mobility of Black Americans who are entering adulthood in the 2000s will be higher than for the parents’ generation, but we don’t yet know how big, in terms of the impact on intergenerational social mobility.

But—Act Now on Race Gaps

Fresher facts, like those being collected by Raj Chetty’s Equality of Opportunity project which includes data for individuals born as late as 1993, will be needed before we can come to really firm conclusions about the relationship between race and mobility in the post-Civil Rights era.

But looking at current trends in residential segregation, pay and employment gaps, and differing school quality by race, it is clear that the challenges facing young black Americans need to be addressed now. The data limitations mean we don’t know everything, especially about long-term trends. But we know enough to act.

Commentary

Social Mobility Data: How Much Can the Past Teach Us About the Present?

April 25, 2014