Recent weeks have been tumultuous for the Trump administration’s approach to climate change and particularly its participation in the Paris Climate Agreement. After it appeared that President Trump was about to pull out of the Paris Agreement just ahead of a United Nations negotiating meeting this past week, the decision was abruptly postponed. Then, in a recent meeting of the eight nations of the Arctic Council, Secretary of State Rex Tillerson stated that the U.S. will now take its time to consider its approach to ensure that it is in line with U.S. interests: “We’re not going to rush to make a decision. We’re going to work to make the right decision for the United States.”

A decision on Paris is now expected after the upcoming G-7 summit in Taormina, Italy, from May 26 to 27 where world leaders will likely present a united front in pressing for the U.S. to remain engaged. While the administration’s orientation toward international coordination on climate change has remained largely opaque, an approach that carefully considers the benefits to the U.S. would be a significant improvement over making this portentous decision simply based on a politically expedient campaign promise.

As the White House mulls its decision, it should keep in mind how the world has evolved rapidly beyond problems that have plagued the economic, technological, and political approaches to climate policy in the past. Despite this, recent Trump administration statements have been erratic and have posited a number of outdated arguments that could easily be dated to the early George W. Bush administration or earlier. Just as today’s global climate toolkit has transformed, the domestic opportunities and logic of the current international approach should also change. If the White House does in fact intend to consider carefully its options, it should consider six shifts that have occurred over the past 20 years:

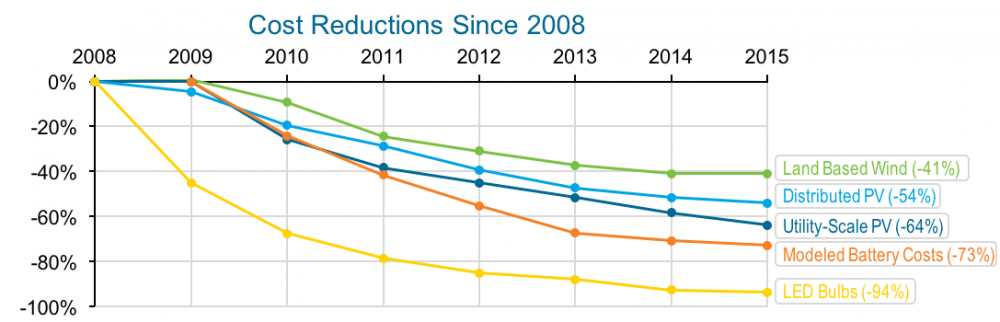

- America’s clean energy revolution makes new U.S. targets achievable. We are in a completely different energy market now compared to 20, 10, and even 5 years ago. Developments in the American energy technology portfolio have been rapid and surprising, as deployment and innovation has accelerated. Levels of clean energy deployment that would have been thought borderline infeasible 20 years ago are now not only in reach but can now be cost-competitive with, and in many situations cheaper than, fossil energy sources. And these trends will continue. Clean energy technologies like PV and LED light bulbs, and to some degree wind, are mass-manufactured and like similar items (e.g., smartphones) tend to become cheaper and better over time. As deployment of such technologies has accelerated globally over recent years, in large part due to clean energy policies in the U.S., Germany, U.K., India, and China, the increased production volumes have helped drive down costs. With many countries planning further rapid clean energy deployment in the coming decade to address climate change, we can expect continued improvements in the costs of clean energy technology.

There are two implications of this trend. First is achieving ambitious climate goals in the U.S. is feasible and cost effective, since these technologies in many cases do not come at a premium and also bring benefits for health and climate.

There are two implications of this trend. First is achieving ambitious climate goals in the U.S. is feasible and cost effective, since these technologies in many cases do not come at a premium and also bring benefits for health and climate. Second, there are opportunities in technology and innovation for the American economy. In expanding technological options in rooftop solar, battery storage, and electric vehicles, Tesla is just one example of the kind of clean energy business that can both innovate and generate employment.

Figure 1: Cost reductions in clean energy costs since 2008

Source: US DOE https://energy.gov/revolution-now

- Most businesses support the Paris Agreement. The American business community, across almost all sectors, is widely in favor of continued international engagement on climate. Unlike previous eras, businesses are not “polarized” or split roughly 50-50 for or against climate policy. Instead, a small number of narrow interests (e.g., the coal industry, which employs roughly only around 0.1 percent of U.S. workers) oppose engagement against a much broader swath of the economy who support a careful U.S. policy approach and an international approach coordinated under the Paris Agreement. To make this point, large groups of American and multinational companies have organized to send messages of support for engagement. One group of 1,000 large and small companies with a market capitalization of $3.4 trillion signed a “Business Backs Low Carbon USA” letter; other groups have sent letters of support directly to Trump or have taken out advertisements publicizing their support. The companies are a “who’s who” of businesses and include Apple Inc., DuPont, Hewlett Packard Enterprise, Hilton, Hewlett Packard, Intel Corp., Johnson & Johnson, Facebook, Google, Microsoft Corp., Morgan Stanley, BP, General Mills Inc., Novartis, Rio Tinto PLC, Shell, Unilever, and Walmart, to name just a few. General Electric Co. CEO Jeff Immelt has repeatedly expressed his support. As an indication of the breadth of support, American oil companies Exxon Mobile and Conoco Phillips have also argued for engaging in the Paris process.

- Clean energy jobs are outpacing traditional fossil jobs. A close counterpart of business engagement and clean energy costs is the potential impact of climate engagement on jobs and the economy. Recent data from the U.S. Department of Energy give a sense of relative sizes of employment. These data indicate that 3 million jobs are linked to clean energy, which includes 475,000 jobs in solar and wind energy. These are also quickly growing categories, having enjoyed growth of 25 percent and 32 percent respectively from 2015 to 2016. In contrast, coal supports about 160,000 jobs including 52,000 in mining. Natural gas and oil industries employ about 915,000 people, bioenergy about 130,000, and nuclear about 76,000. The numbers are clear in demonstrating a large segment of the U.S. energy sector moving into cleaner technologies.

- A majority of Americans, majority of Democrats, and majority of Republicans support Paris. Polling has shown marked growth in support for international climate action over recent years. A recent poll by the Chicago Council on Global Affairs showed a relatively strong 71 percent support for staying in Paris, with 57 percent support even for Republicans. Another study by the Yale Program on Climate Communication and the George Mason Center for Climate Communication shows 69 percent support for participating in the Paris Agreement, with 51 percent of Republicans supporting. Perhaps even more surprisingly, that study also showed that even among conservative (i.e., non-moderate) Republicans, fully 34 percent support engagement via Paris against 40 percent opposed, with the rest undecided. The polling evidence demonstrates that, as with the business community, a large portion of the American public supports engagement in climate-smart policies, and specifically an international approach under Paris. Other polling has shown that public support becomes even stronger when the health benefits of cleaner energy (avoided deaths, fewer heart and asthma conditions, lost school and workdays, etc.) are included in the overall framing of options. With even many in the Republican Party looking for solutions, continued engagement offers more opportunities for constituents to have their voices reflected and recognized in advance of upcoming elections.

- The flexibility of the Paris Agreement favors U.S. interests in negotiations. Environmental Protection Agency Administrator Scott Pruitt recently stated that under the Paris Agreement, China and India had no obligations until 2030 even though they were polluting more. This assertion is simply untrue (and indeed earned a full “Four Pinocchios” from the Washington Post’s Fact Checker). The reason is that the Paris Agreement was designed with the express purpose of solving this particular problem—and by including all major polluters in a common framework, the Paris Agreement includes both China and India (as well as all other key emitters) who have both opted to set emissions targets that require substantial near-term action on their part. Pruitt mounted a criticism used commonly 20 years ago—and was typically applied to bash the Kyoto Protocol. In the interim, the world listened to the critique and acted to create an international agreement that addresses these concerns.

Quite simply, it’s about as good a structure as we are ever going to get in that it encourages international action while respecting that overall policies will always be set at the national level.

Specifically, the new international agreement struck in Paris was expressly designed with a robust, flexible structure based on the principle of national determination and global transparency. Quite simply, it’s about as good a structure as we are ever going to get in that it encourages international action while respecting that overall policies will always be set at the national level. It therefore does not (contrary to some fears reportedly in the Trump administration) bind the U.S. to an externally imposed plan, and it does in fact provide a framework in which all countries participate and set emissions goals on an equal footing—including China and India. As such, although Secretary of Energy Rick Perry recently called for a “renegotiation” of Paris, he and the rest of the Trump administration will likely discover that there is nothing more to be gained from renegotiating. Anything the U.S. would want to do regarding our approach to climate can be done within the context of Paris. Remaining part of that process gives us the best leverage to ensure that other countries are participating on terms that the U.S. believes provide the fairest playing field and the best chance for a positive climate outcome.

- Withdrawing from Paris would cause severe international fallout. The science of climate change is now well known and the implications of this science are both harrowing and widely understood in countries around the world. While countries have differing approaches to the near-term strategies to reduce emissions in their own economies, both major powers and smaller countries have become concerned about the impacts of climate change on their own populations and economies. The global initiative to negotiate the Paris Agreement, which required substantial effort from many countries (not least the U.S.), is a testament to this broad support for coordinated climate action. In this light, many countries view an American pullout from Paris as an aggressive action against their own populations. Many have expressed anger and dismay that the anti-climate actions of the U.S. would make such outcomes more likely. Whether or not Trump agrees, many countries will nevertheless interpret a U.S. pullout not as simply a domestic issue but as a deliberate, unnecessary, and hostile act against their own interests.

This situation creates geopolitical consequences. When many countries weigh engagement with climate heavily, a U.S. withdrawal would squander a large amount of political capital in bilateral and multilateral relations for a fleeting and inconsequential domestic political benefit. World leaders have prioritized this issue and are not sitting still. For example, when Trump called to congratulate newly elected French President Emmanuel Macron, Macron immediately used the opportunity to press Trump to keep the U.S. in the Paris Agreement. The next day, Chinese President Xi Jinping also discussed the issue with Macron and agreed to, in his words, “defend” the Paris agreement. China in particular has a great interest in portraying itself as defending developing, vulnerable countries against climate change globally, which will also support its broader efforts to cultivate favor in a number of developing countries (for example, in Africa, Asia, and Latin America) with which it is seeking greater economic and political influence.

Trump has been deploying 19th century technology and 20th century political arguments in the face of a 21st century problem.

In addition to these six areas of change, there is of course one more development that is important: Trump is now president with the power to shape the U.S. federal regulatory environment and international engagement. So far, when it comes to climate change, Trump has been deploying 19th century technology and 20th century political arguments in the face of a 21st century problem. The good news is that the world has already fixed the critiques that Trump administration officials have levied at the Paris Agreement. The big developing countries are also taking steps to reduce their emissions, and U.S. engagement has given us political benefits internationally. In this context, withdrawing would be a Pyrrhic victory for Trump, producing a temporary talking point, temporarily increased support from a small group of political actors in the U.S., but creating tremendous international blowback and long-term damage to U.S. interests. Moreover, and most importantly, it would slow global efforts to address the issue and make riskier and more damaging climate outcomes—to both U.S. and global interests—more likely.

The rational calculus for American interests is clear, but it remains the president’s decision.

Commentary

As Trump weighs Paris Climate agreement, 6 ways the world has changed

May 12, 2017