Content from the Brookings Doha Center is now archived. In September 2021, after 14 years of impactful partnership, Brookings and the Brookings Doha Center announced that they were ending their affiliation. The Brookings Doha Center is now the Middle East Council on Global Affairs, a separate public policy institution based in Qatar.

Since the onset of the Arab uprisings 10 years ago, many people from Bahrain, Egypt, Libya, Syria, Yemen, and other countries have fled or were forced to flee their home states. The demography of these new diasporas is diverse and powerful, yet policymakers in the West do not adequately engage with them.

These emerging and politically active post-2011 Arab diasporas include former politicians and diplomats, academics, activist lawyers, civil society professionals, doctors, judges, journalists, and artists. Many of these diasporic actors plan to return home once the situation allows them to do so safely. They exert a fair amount of effort to try and influence and inform policies that affect their home state. And while the role of states remains central to the conduct of international relations, policymakers should pay more attention to these new Arab diasporas and use them in identifying solutions to armed conflict and problems of governance.

Importantly, they form part of a new diasporic community rather than a more established diaspora whose ties to the home state are more distant. While many members of these new Arab diasporas are young intellectuals and civil society professionals, many are also experienced politicians and human rights lawyers, whose work is essentially the reason they were forced to flee. They retain strong ties to their home state and have access to host state policymakers, international policymakers, NGOs, and media; and to war crimes prosecutors in Europe.

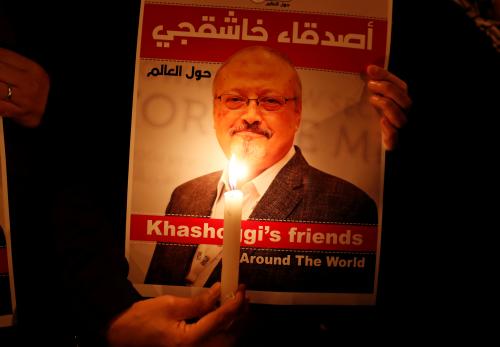

Arab states increasingly view these new diasporic actors as a threat. The murder of Saudi Washington Post journalist Jamal Khashoggi is one of many examples from across the Arab region. The extent to which other governments will go to warn their citizens abroad was made ominously clear by Nabila Makram, the Egyptian minister of immigration and expatriate affairs. During a visit to Canada in 2019, Makram warned that anybody who criticizes Egypt abroad will be “punished” and she gestured with a slicing motion across her neck as she made the remark. Earlier this month, Makram stated that Egyptian researchers abroad are one of the most “dangerous” segments of the country’s diaspora, arguing that they import ideas that harm Egypt.

Such examples attest to the perceived influence that diasporic professionals who actively engage in issues concerning their home state exert. They are mobile and relatively secure in comparison to their fellow nationals at home, despite increasing attempts to crack down on them transnationally. They make an impact on issues ranging from the pursuit of accountability for crimes committed in their home states, to generating and exchanging policy-oriented ideas to help resolve conflict, counter repression, and build peace at home.

Foreign policy practitioners should do more to systematically engage with these new Arab diasporas. Thus far, such engagement has been largely ad hoc.

A strategy that establishes safe spaces for sustained engagement would allow for the knowledge and experience of such diasporic actors to better inform policymaking to address the complex challenges facing the Arab region. This is particularly important as several states are either experiencing armed conflict and state fragmentation or renewed authoritarianism.

However, engaging with diasporic actors must be approached carefully. Overreliance on certain individuals, especially elite political exiles who have been abroad for a long time, can be detrimental. Some are either out of touch with the home state, while others have a self-absorbed political agenda that detracts from and even challenges the broader goals of conflict resolution and better governance. The likes of former Iraqi Deputy Prime Minister Ahmad Chalabi, former Iraqi Vice President Ayad Allawi, and even Libyan military commander Khalifa Hifter are examples of such individuals. While adept at canvassing support from Western policymakers, their legitimacy immediately came into question once they reached a position of power at home.

But this is why more — and not less — engagement with new Arab diasporas is crucial. This is particularly true for diasporic academics, policy specialists, and civil society professionals working in a variety of fields including public health, education, security, human rights, counterterrorism, and peacebuilding. As many of them left or were forced to flee following the unraveling of the Arab uprisings, their work abroad is an extension of the work they did before. This lends a certain level of legitimacy to these new diasporic actors with their compatriots at home. However, the longer they remain abroad, the greater the chances that their perceived legitimacy will weaken.

The shrinking of the civic space in several countries across the Arab region, which has seen the obsessive enactment of laws that restrict the work of NGOs as well as their very existence, has led to several civil society organizations relocating to outside of their home states. Many have also established new think tanks and civil society organizations abroad, where they coordinate efforts geared towards shaping policy, knowledge production, and seeking accountability.

It is these cohorts of the new Arab diasporas that foreign policymakers should work with more systematically to better inform policymaking.

For example, while efforts to end the war in Yemen continue to fail, Yemenis in the new diaspora, especially those who fled since 2014, have identified and proposed approaches for a political transition that would carefully lay the foundations for Yemeni-led governance.

One such proposal is to create a presidential council with a limited mandate in Yemen. Such a council would oversee peace talks and appoint Yemenis to high-level government positions, including that of prime minister. The Sanaa Center for Strategic Studies argues that this council would serve as “a first step in a much-needed process of comprehensive governance reform.”

Nothing prevents such a council from including some of the most experienced and politically astute Yemenis in the diaspora. Ironically, while the current Yemeni government headed by Abed Rabbo Mansour Hadi has operated from outside Yemen — in Riyadh — the potential replacement of this weak government could also partially include those who have (unwillingly) resided outside Yemen.

The new Syrian diaspora has made significant achievements in transitional justice. In addition to the robust Syrian documentation movement, activist lawyers in the Syrian diaspora, along with victims and relatives of victims who became refugees, have built many criminal cases in several European states targeting high-level officials of the Assad regime. They have done so in collaboration with Syrians inside Syria and abroad. These developments are an attestation to the value of effective cooperation between experts from a particular diaspora and their allies in the international community.

Still, knowledge production by Arab intellectuals, practitioners, and policy analysts both in their home states and in the diaspora often continues to be ignored, even dismissed, by international policymakers. More attention is needed for effective ways to engage with the experience and expertise of these communities.

Finally, a major challenge that new Arab diasporas face is polarization fueled by social media, disinformation, transnational surveillance by the home state, and many other factors. In my conversations with active Yemenis, Libyans, and Egyptians in particular, the lack of sufficient safe spaces in which they could exchange ideas without fear of repercussions is a major obstacle to effective coordination and mobilization.

Foreign policymakers can and should work to establish safe spaces and to weaken the transnational reach of repressive state security agencies that target their citizens abroad.

As I argued in this Brookings report, diaspora members should be key partners in shaping the international and domestic policies that affect them, especially as they are an immediately accessible and valuable resource for policymakers during the conflict, transitional, and post-conflict periods.

This can be done in at least three ways. First, the State Department’s Near Eastern Affairs bureau could appoint an official to liaise with key Arab diasporic actors who have temporarily resettled in the U.S. There should be a concerted effort to seek out civil society professionals who work in multiple sectors and whose safety can be secured throughout this kind of engagement. Language and area expertise would be vital.

Secondly, as Arab diasporic members are dispersed and concentrated in different locations across Europe, North America, the Gulf region, and Southeast Asia, an effective strategy would be to designate diaspora liaison officials across key U.S. embassies in other parts of the world. The primary role of such officials would be to establish and grow a network of new Arab diasporic actors who have the knowledge and experience to inform policymaking. In doing so, policymakers would be able to keep their finger on the pulse of shifting politics and on realistic approaches to policy that could generate desired outcomes.

Finally, as think tanks continue to exert influence in the policymaking field, they should make a conscious effort to provide more platforms for new Arab diasporic actors to share their ideas on the pressing policy issues facing their home states and the broader region. Such platforms should include both public and confidential spaces of engagement, which would encourage those who are wary of the “long arm of the Arab state” to participate. Strategically engaging with new Arab diasporas in this way would diversify and strengthen the policy solutions available for practitioners.

Commentary

How Western policymakers can engage the new Arab diasporas

July 16, 2021