To get ahead of new problems related to disinformation and technology, policymakers in Europe and the United States should focus on the coming wave of disruptive technologies, write Chris Meserole and Alina Polyakova. Fueled by advances in artificial intelligence and decentralized computing, the next generation of disinformation promises to be even more sophisticated and difficult to detect. This piece originally appeared on ForeignPolicy.com.

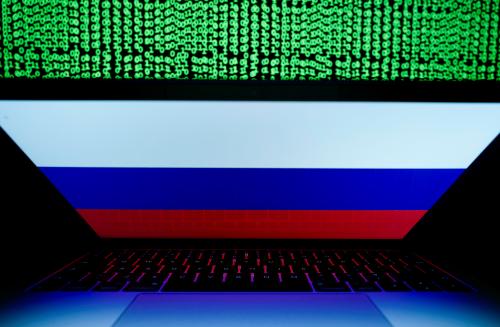

Russian disinformation has become a problem for European governments. In the last two years, Kremlin-backed campaigns have spread false stories alleging that French President Emmanuel Macron was backed by the “gay lobby,” fabricated a story of a Russian-German girl raped by Arab migrants, and spread a litany of conspiracy theories about the Catalan independence referendum, among other efforts.

Europe is finally taking action. In January, Germany’s Network Enforcement Act came into effect. Designed to limit hate speech and fake news online, the law prompted both France and Spain to consider counterdisinformation legislation of their own. More important, in April the European Union unveiled a new strategy for tackling online disinformation. The EU plan focuses on several sensible responses: promoting media literacy, funding a third-party fact-checking service, and pushing Facebook and others to highlight news from credible media outlets, among others. Although the plan itself stops short of regulation, EU officials have not been shy about hinting that regulation may be forthcoming. Indeed, when Facebook CEO Mark Zuckerberg appeared at an EU hearing this week, lawmakers reminded him of their regulatory power after he appeared to dodge their questions on fake news and extremist content.

The problem is that technology advances far more quickly than government policies.

The recent European actions are important first steps. Ultimately, none of the laws or strategies that have been unveiled so far will be enough. The problem is that technology advances far more quickly than government policies. The EU’s measures are still designed to target the disinformation of yesterday rather than that of tomorrow.

To get ahead of the problem, policymakers in Europe and the United States should focus on the coming wave of disruptive technologies. Fueled by advances in artificial intelligence and decentralized computing, the next generation of disinformation promises to be even more sophisticated and difficult to detect.

To craft effective strategies for the near term, lawmakers should focus on four emerging threats in particular: the democratization of artificial intelligence, the evolution of social networks, the rise of decentralized applications, and the “back end” of disinformation.

Thanks to bigger data, better algorithms, and custom hardware, in the coming years, individuals around the world will increasingly have access to cutting-edge artificial intelligence. From health care to transportation, the democratization of AI holds enormous promise.

Yet as with any dual-use technology, the proliferation of AI also poses significant risks. Among other concerns, it promises to democratize the creation of fake print, audio, and video stories. Although computers have long allowed for the manipulation of digital content, in the past that manipulation has almost always been detectable: A fake image would fail to account for subtle shifts in lighting, or a doctored speech would fail to adequately capture cadence and tone. However, deep learning and generative adversarial networks have made it possible to doctor images and video so well that it’s difficult to distinguish manipulated files from authentic ones. And thanks to apps like FakeApp and Lyrebird, these so-called “deep fakes” can now be produced by anyone with a computer or smartphone. Earlier this year, a tool that allowed users to easily swap faces in video produced fake celebrity porn, which went viral on Twitter and Pornhub.

Deep fakes and the democratization of disinformation will prove challenging for governments and civil society to counter effectively. Because the algorithms that generate the fakes continuously learn how to more effectively replicate the appearance of reality, deep fakes cannot easily be detected by other algorithms—indeed, in the case of generative adversarial networks, the algorithm works by getting really good at fooling itself. To address the democratization of disinformation, governments, civil society, and the technology sector therefore cannot rely on algorithms alone, but will instead need to invest in new models of social verification, too.

At the same time as artificial technology and other emerging technologies mature, legacy platforms will continue to play an outsized role in the production and dissemination of information online. For instance, consider the current proliferation of disinformation on Google, Facebook, and Twitter.

A growing cottage industry of search engine optimization (SEO) manipulation provides services to clients looking to rise in the Google rankings. And while for the most part, Google is able to stay ahead of attempts to manipulate its algorithms through continuous tweaks, SEO manipulators are also becoming increasingly savvy at gaming the system so that the desired content, including disinformation, appears at the top of search results.

For example, stories from RT and Sputnik—the Russian government’s propaganda outlets—appeared on the first page of Google searches after the March nerve agent attack in the United Kingdom and the April chemical weapons attack in Syria. Similarly, YouTube (which is owned by Google) has an algorithm that prioritizes the amount of time users spend watching content as the key metric for determining which content appears first in search results. This algorithmic preference results in false, extremist, and unreliable information appearing at the top, which in turn means that this content is viewed more often and is perceived as more reliable by users. Revenue for the SEO manipulation industry is estimated to be in the billions of dollars.

On Facebook, disinformation appears in one of two ways: through shared content and through paid advertising. The company has tried to curtail disinformation across each vector, but thus far to no avail. Most famously, Facebook introduced a “Disputed Flag” to signify possible false news—only to discover that the flag made users more likely to engage with the content, rather than less. Less conspicuously, in Canada, the company is experimenting with increasing the transparency of its paid advertisements by making all ads available for review, including those micro-targeted to a small set of users. Yet, the effort is limited: The sponsors of ads are often buried, requiring users to do time-consuming research, and the archive Facebook set up for the ads is not a permanent database but only shows active ads. Facebook’s early efforts do not augur well for a future in which foreign actors can continue to exploit its news feed and ad products to deliver disinformation—including deep fakes produced and targeted at specific individuals or groups.

Although Twitter has taken steps to combat the proliferation of trolls and bots on its platform, it remains deeply vulnerable to disinformation campaigns, since accounts are not verified and its application programming interface, or API, still makes it possible to easily generate and spread false content on the platform. Even if Twitter takes further steps to crack down on abuse, its detection algorithms can be reverse-engineered in much the same way Google’s search algorithm is. Without fundamental changes to its API and interaction design, Twitter will remain rife with disinformation. It’s telling, for example, that when the U.S. military struck Syrian chemical weapons facilities in April—well after Twitter’s latest reforms were put in place—the Pentagon reported a massive surge in Russian disinformation in the hours immediately following the attack. The tweets appeared to come from legitimate accounts, and there was no way to report them as misinformation.

Blockchain technologies and other distributed ledgers are best known for powering cryptocurrencies such as bitcoin and ethereum. Yet their biggest impact may lie in transforming how the internet works. As more and more decentralized applications come online, the web will increasingly be powered by services and protocols that are designed from the ground up to resist the kind of centralized control that Facebook and others enjoy. For instance, users can already browse videos on DTube rather than YouTube, surf the web on the Blockstack browser rather than Safari, and store files using IPFS, a peer-to-peer file system, rather than Dropbox or Google Docs. To be sure, the decentralized application ecosystem is still a niche area that will take time to mature and work out the glitches. But as security improves over time with fixes to the underlying network architecture, distributed ledger technologies promise to make for a web that is both more secure and outside the control of major corporations and states.

If and when online activity migrates onto decentralized applications, the security and decentralization they provide will be a boon for privacy advocates and human rights dissidents. But it will also be a godsend for malicious actors. Most of these services have anonymity and public-key cryptography baked in, making accounts difficult to track back to real-life individuals or organizations. Moreover, once information is submitted to a decentralized application, it can be nearly impossible to take down. For instance, the IPFS protocol has no method for deletion—users can only add content, they cannot remove it.

For governments, civil society, and private actors, decentralized applications will thus pose an unprecedented challenge, as the current methods for responding to and disrupting disinformation campaigns will no longer apply. Whereas governments and civil society can ultimately appeal to Twitter CEO Jack Dorsey if they want to block or remove a malicious user or problematic content on Twitter, with decentralized applications, there won’t always be someone to turn to. If the Manchester bomber had viewed bomb-making instructions on a decentralized app rather than on YouTube, it’s not clear who authorities should or could approach about blocking the content.

Over the last three years, renewed attention to Russian disinformation efforts has sparked research and activities among a growing number of nonprofit organizations, governments, journalists, and activists. So far, these efforts have focused on documenting the mechanisms and actors involved in disinformation campaigns—tracking bot networks, identifying troll accounts, monitoring media narratives, and tracing the diffusion of disinformation content. They’ve also included governmental efforts to implement data protection and privacy policies, such as the EU’s General Data Protection Regulation, and legislative proposals to introduce more transparency and accountability into the online advertising space.

While these efforts are certainly valuable for raising awareness among the public and policymakers, by focusing on the end product (the content), they rarely delve into the underlying infrastructure and advertising markets driving disinformation campaigns. Doing so requires a deeper examination and assessment of the “back end” of disinformation. In other words, the algorithms and industries—the online advertising market, the SEO manipulation market, and data brokers—behind the end product. Increased automation paired with machine learning will transform this space as well.

To get ahead of these emerging threats, Europe and the United States should consider several policy responses.

First, the EU and the United States should commit significant funding to research and development at the intersection of AI and information warfare. In April, the European Commission called for at least 20 billion euros (about $23 billion) to be spent on research on AI by 2020, prioritizing the health, agriculture, and transportation sectors. None of the funds are earmarked for research and development specifically on disinformation. At the same time, current European initiatives to counter disinformation prioritize education and fact-checking while leaving out AI and other new technologies.

As long as tech research and counterdisinformation efforts run on parallel, disconnected tracks, little progress will be made in getting ahead of emerging threats.

As long as tech research and counterdisinformation efforts run on parallel, disconnected tracks, little progress will be made in getting ahead of emerging threats. In the United States, the government has been reluctant to step in to push forward tech research as Silicon Valley drives innovation with little oversight. The 2016 Obama administration report on the future of AI did not allocate funding, and the Trump administration has yet to release its own strategy. As revelations of Russian manipulation of digital platforms continue, it is becoming increasingly clear that governments will need to work together with private sector firms to identify vulnerabilities and national security threats.

Furthermore, the EU and the U.S. government should also move quickly to prevent the rise of misinformation on decentralized applications. The emergence of decentralized applications presents policymakers with a rare second chance: When social networks were being built a decade ago, lawmakers failed to anticipate the way in which they could be exploited by malicious actors. With such applications still a niche market, policymakers can respond before the decentralized web reaches global scale. Governments should form new public-private partnerships to help developers ensure that the next generation of the web isn’t as ripe for misinformation campaigns. A model could be the United Nations’ Tech Against Terrorism project, which works closely with small tech companies to help them design their platforms from the ground up to guard against terrorist exploitation.

Finally, legislators should continue to push for reforms in the digital advertising industry. As AI continues to transform the industry, disinformation content will become more precise and micro-targeted to specific audiences. AI will make it far easier for malicious actors and legitimate advertisers alike to track user behavior online, identify potential new users to target, and collect information about users’ attitudes, beliefs, and preferences.

In 2014, the U.S. Federal Trade Commission released a report calling for transparency and accountability in the data broker industry. The report called on Congress to consider legislation that would shine light on these firms’ activities by giving individuals access and information about how their data is collected and used online. The EU’s protection regulation goes a long way in giving users control over their data and limits how social media platforms process users’ data for ad-targeting purposes. Facebook is also experimenting with blocking foreign ad sales ahead of contentious votes. Still, the digital ads industry as a whole remains a black box to policymakers, and much more can still be done to limit data mining and regulate political ads online.

Effectively tracking and targeting each of the areas above won’t be easy. Yet policymakers need to start focusing on them now. If the EU’s new anti-disinformation effort and other related policies fail to track evolving technologies, they risk being antiquated before they’re even introduced.

Commentary

The West is ill-prepared for the wave of “deep fakes” that artificial intelligence could unleash

May 25, 2018