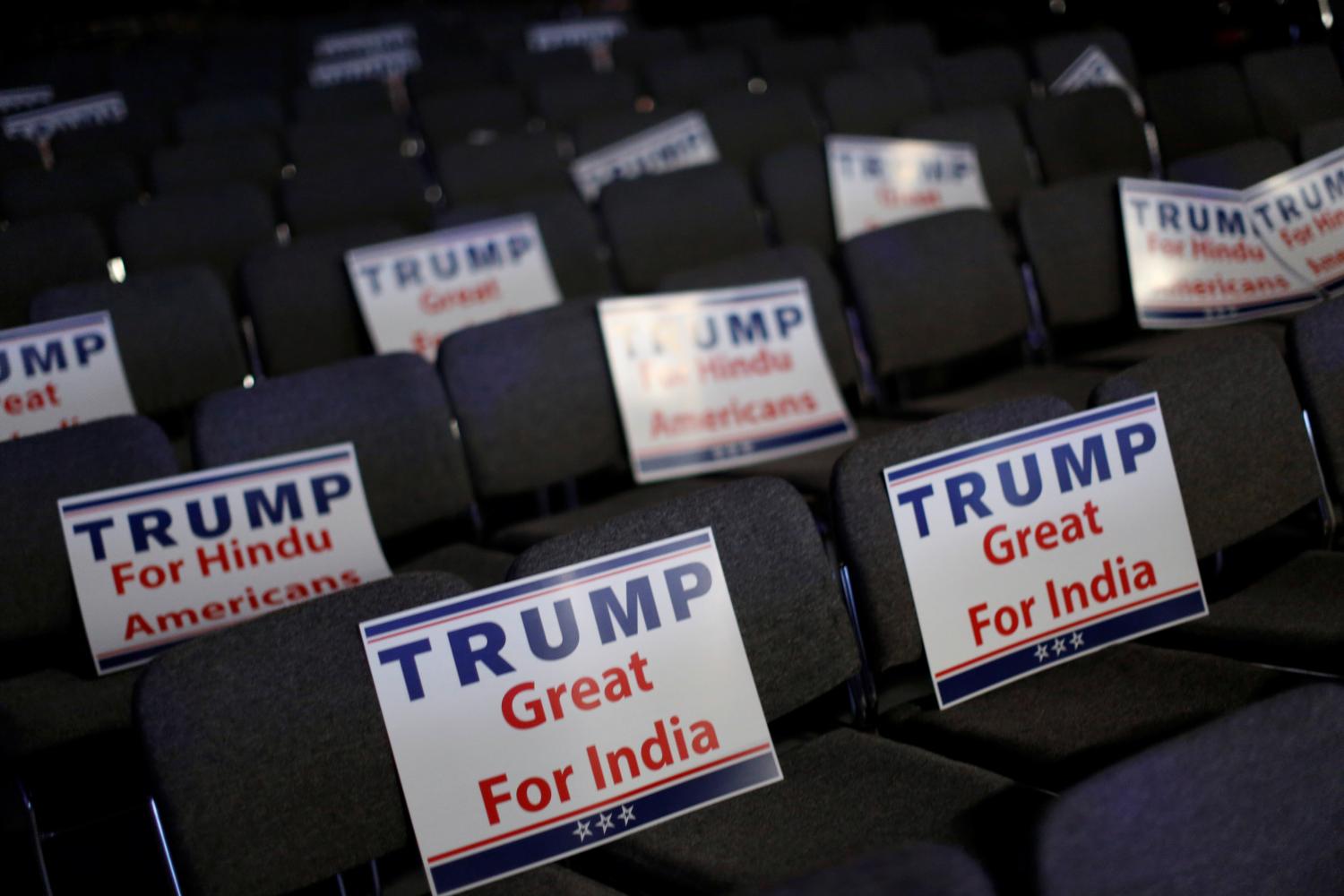

“I’m a big fan of India,” declared Donald Trump at a recent event organized by one of his Indian-American donors, which led to a round of articles exploring subjects like “why Donald Trump is popular with a lot of people in India.”

The verdict on Trump in India, however, is much more mixed. The Indian government, on its part, has predictably said that it is a decision for the American public and Delhi will deal with whoever comes to power. Officials have stated that the U.S.-India relationship is driven by factors—and held together by links—that will persist regardless of who is president. But both in style and substance, the choice is starker than it has been in most elections, and for the Indian government, a Trump presidency would throw up a number of concerns and questions that it wouldn’t necessarily have had with any other Republican nominee.

Trump on India

Trump has mentioned India sparingly, probably much to Indian policymakers’ relief. When he has mentioned the country, it has been in one of two ways:

- the “winning” avatar: India, the country that “is doing great” these days, that he sees not as an “emerging market” but an “amazing market.” This India is an opportunity—among other things, the site of future Trump-branded properties.

- the “sad!” avatar: India, the country that’s taking American jobs and, along with China and other countries, eating America’s lunch—or, as Trump has put it, its candy. This India is a challenge, a country that “takes advantage” and is “ripp[ing] off the U.S.”

Not unusually, Trump’s categories aren’t neatly divided. For example, at an event he first mimicked Indian call center workers to complain about outsourcing, but then said “India is a great place.” He’s complained about Indians taking American jobs, but also emphasized that he has “tremendous jobs” going up in India.

India on Trump

Indians have taken a greater than usual interest in this election and in Trump. On the one hand, he is a presidential nominee that is more familiar to Indians than any other candidate has been in history; on the other, perhaps the least familiar one—at least in terms of his politics and policies. There have been multiple discussions about whether Trump would be good or bad for India. There’s been coverage of Indian-Americans who support or oppose Trump, as well as attention on—and criticism about—his views of minorities and immigrants. There have also been comparisons with Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi and the 2014 Indian election, while others have called these comparisons simplistic.

Indian officials, on their part, have declined to comment publicly on the race. This election cycle has posed a particular problem: Indian officials are not unfamiliar with the Republican establishment—indeed, some believe that Republicans have been better for India than Democrats—but Trump is not a typical Republican, and many Republicans they know in the foreign policy establishment have said they’d never work in a Trump administration. Thus, over the last few months, like many governments, they have tried to figure out who is close to Trump and to reach out to them. In July, the government reportedly set up a group of six analysts “to help identify ways to engage with Trump.” Former Indian political and bureaucratic officials have been more vocal. For example, former Indian foreign minister from the Congress party Salman Khurshid has said India would be “very, very worried” about a Trump presidency and called Trump’s views “extreme” and “alarming.”

There are those in India who think a Trump presidency wouldn’t be bad for the country. Some point to his remarks about the danger posed by terrorism or Pakistani nuclear weapons. He’s also found support among those who approve of his rhetoric on “radical Islamic terrorism.” With Modi’s penchant for personal diplomacy, there’s also a view that Trump and he can connect (not just in India; former House Speaker Newt Gingrich said the two leaders would “enjoy each other.”) Others hope that a President Trump would put less pressure on issues related to climate change, especially on fossil fuel usage, or human rights.

There’s also less concern about Trump’s attitude toward Russia than you’d find in other countries—Russia remains a partner for India, and Delhi has indeed been concerned that Moscow has been pushed toward China because of the strained relationship with the United States and Western Europe. For others, it’s relative; they think Trump will be better than Hillary Clinton, who engenders a range of reactions in India, as well as a conspiracy theory or two.

The uncertainties

However, there are elements of Trump’s proposals that would give senior Indian officials major pause. Overall, there’s the uncertainty and unpredictability of his approach. This would come at a time of many other uncertainties around the world, with regional geopolitical orders in flux and a debate in the West about globalization that has implications for countries’ stances on trade and immigration.

It would also come at a critical time for India in terms of its growth trajectory—one in which it has envisioned the United States playing a crucial role. For the last couple of decades, there’s largely been bipartisan support for the India relationship in the United States, with different administrations’ approaches falling within a certain spectrum. With Trump, however, would come a number of known unknowns and unknown unknowns—in terms of U.S. engagement with the world in general and policy towards specific countries in particular—that could affect India’s interests.

With Trump, however, would come a number of known unknowns and unknown unknowns.

U.S. strategic and economic engagement with the world. Delhi would have serious concerns with a disengaging United States. India hasn’t always agreed with American foreign policy, particularly when it’s involved interventionism, but it has benefited from the U.S. role in its region—for example, Delhi sees the United States as playing a critical role in ensuring a multipolar Asia and securing the sea lines of communication. Delhi also sees the U.S.-India relationship as giving India leverage with other countries.

Economically, the United States is India’s largest trading partner (if you count goods and services), and one of its major investors. This is particularly important at a time when India is strengthening itself economically and military—it needs partners for that process, and the past few Indian governments have seen the United States as crucial in this regard. Modi has indeed identified the United States as a “a principal partner in the realization of India’s rise,” with President Obama, in turn, stating that India’s rise is in American interest.

Trump, however, has a much narrower definition of national interest, bluntly saying: “we have to take care of ourselves” and suggesting that others—especially allies and partners—have been free-riding for too long. With a Trump presidency, Delhi might have to face the reality of getting what rhetorically some in India have claimed to want: a United States that minds its own business. Some have argued that an American retrenchment could create opportunity for Delhi, but India is not currently in a position to fill that vacuum effectively. Thus, for a government that has invested heavily in the U.S. relationship and a country that has benefited from a rules-based order, such disengagement would not be a welcome development at this stage. Moreover, Trump’s made clear he would still unilaterally use force if he saw fit to do so (for example, against Iran).

[F]or a government that has invested heavily in the U.S. relationship and a country that has benefited from a rules-based order, such disengagement would not be a welcome development at this stage.

Trump’s transactionalism. There is a related issue with which Delhi will have to grapple: transactionalism. Both Presidents Bush and Obama saw their investment in the India relationship—not insignificant, given other domestic and foreign policy preoccupations—as a long-term proposition. That is, as a relationship that might have limited pay-offs for the United States in the short term, but would show major returns over the medium to long term.

However, Trump is far more transactional and would likely want India to put more on the table immediately. Indian policymakers have been known to complain that the United States can be too transactional, but a Trump presidency would make this concern much more acute. What would India do if a President Trump demanded compensation for U.S. protection of the sea lines of communication? Or complained that the U.S.-India civil nuclear agreement was a bad deal because the United States has little to show for it tangibly? Or—reversing the concern that Trump’s foreign business ties could threaten U.S. national security—what if a President Trump sought benefits for his business as a quid pro quo? The Modi government is arguably more comfortable with transactionalism than its predecessors, but the system is not necessarily designed to be able to deliver the kind of deals that Trump might want in a hurry—or without the kind of scrutiny that a non-democracy might get away with.

China policy. One of the major drivers of the U.S.-India relationship has been China’s rise and some shared concerns about its implications. Trump has promised to be tough on China on the economic front, but has been less clear on the strategic front. At best, he’s shown little interest in the U.S. role in Asia; at worst, he’s stated that he’d like to reduce it (or be compensated for it). He’s questioned the value of the Asian alliances—and particularly targeted Japan, a close partner of India—and suggested that the United States shouldn’t care as much about regional issues.

Given the impact it would have on other Asian countries’ security choices, India would see a U.S. disengagement from Asia as destabilizing. The government has come to perceive—and appreciate—the United States as a “resident” power in Asia. There could also be major concern about Trump coming to some sort of understanding or “deal” with China, demanding accommodation of American interests on the economic side, while giving Beijing a free(r) run on the strategic side in the region—making real the G-2 that Delhi worries about. That would leave India with essentially two choices: strike a deal with China or greatly speed up its own military build-up and relationship-building with countries like Japan and Vietnam.

Pakistan policy. Some of Trump’s comments on Pakistan have been received positively, but questions remain about whether he’d really do anything differently and what he’d do to “try and keep” the “little bit of a good relationship” with Pakistan that he said he’d prefer. He’s stated that India could help with Washington’s Pakistan problem, but there is little clarity about what that’d entail, too.

In the past, such suggestions have involved recommendations like asking India to consider concessions on Kashmir. More recently, Trump declined to take sides on India-Pakistan issues, but also remarked that if the two countries wanted him to, “I would love to be the mediator or arbitrator”—India is unlikely to give any American president that opportunity. There had been one additional concern related to senior Trump aide Paul Manafort’s links with Pakistan’s Inter-Services Intelligence, but his removal from the campaign dissipated those worries.

On trade and investment. The United States and India already trade barbs about which country is protectionist: Washington argues it is India, with its trade policies and approach at the World Trade Organization (WTO); and India argues that it’s the United States with plurilateral initiatives like the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP). With Trump talking of being even tougher on trade, these problems would only increase. India might not mourn the TPP’s demise per se, but, for all the rhetoric, an open, outward-looking United States—that is engaged in Asia—has benefited India. Also, unlike Trump, it is a supporter of the WTO, which he has called a disaster and threatened to leave.

Moreover, at the very time that Modi is trying to attract American investment into India (particularly of the job-creating variety), Trump has been calling out companies creating jobs abroad and promised to “bring back jobs” from countries like India. His main super PAC’s first ad, in fact, targeted outsourcing to India. Finally, there is likely to be concern about the implications on the global and U.S. economy of Trump’s economic policies and of potential retaliatory action that they might spark.

[A]n open, outward-looking United States—that is engaged in Asia—has benefited India.

Coming to America. Delhi would also watch with concern some issues that could affect its citizens or diaspora. For one, Trump’s stance on H-1B visas, which has changed multiple times. Senator Jeff Sessions, a close advisor of Trump’s, has called the H-1B program a “tremendous threat” and last year co-sponsored a bill that would have also potentially eliminated the optional practical training program associated with student visas. In the spring, India’s chief economic adviser said some of Trump’s comments on this were “very worrying for export-led growth going forward.”

Second, Trump’s call for a “total and complete shutdown of Muslims entering the U.S.” would cause concern, since India has the second or third largest Muslim population in the world, constituting over 14 percent of its population. And the “ban” has received a fair bit of attention, even invoking responses from cross-over star Priyanka Chopra (“you can’t put a ban on anyone…Generalizing a type of people is really primitive”) and Indian news anchor Arnab Goswami, who pressed Trump supporters on the implications of such a ban for hundreds of millions of Muslims and on potential profiling of Indians visiting the United States.

Third, given the 1.3 million Indian citizens who reside in the United States, as well as the over 3 million Indian Americans, the treatment of minorities—though a domestic issue—will get attention in India (as did a Sikh man’s ejection from a Trump rally or an Indian grandfather’s injuries after an encounter with police in Alabama). It could create demands on a government that has said the safety of Indians abroad is a priority.

Hoping and preparing

A number of Indian observers have dismissed Trump’s talk as campaign rhetoric or expressed confidence in American institutions’ ability to keep his most troubling impulses at bay. If, defying expectations, Trump does become U.S. president, however, the Indian government will have to prepare for any and all eventualities, including the ones outlined above, while working to ensure that India is seen as a key actor to engage with.

But, regardless of who wins on November 8, this election has brought to the fore questions in the United States about globalization, identity politics, America’s role in the world, and the utility of allies and partners that will have implications for countries like India. An understanding of this context is partly the reason Indian policymakers have already been stressing that the U.S.-India relationship is mutually beneficial. On his last visit to the United States, Modi did so himself in a speech to Congress—in which he also referred to the United States as “great” at least four times.

Commentary

Trump, India, and the known unknowns

November 2, 2016