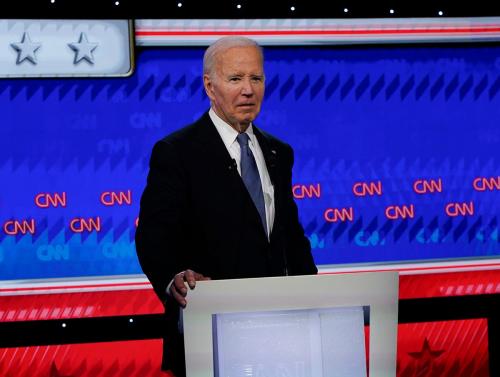

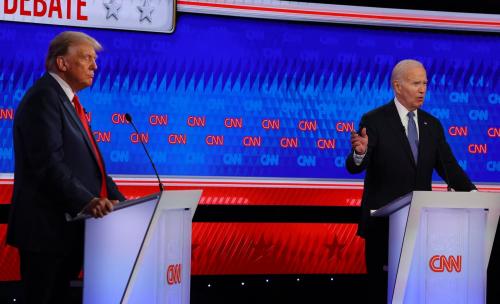

This question would not even be asked were it not for President Biden’s weak performance in his recent debate with Donald Trump—a performance that has called into doubt his ability run and to govern. The question arises against the backdrop of recent American history where delegates have been extras in the convention television show produced for prime time. They cheer on cue, wear colorful patriotic regalia, and offer glowing reviews of their standard-bearers to reporters desperate for a little bit of hard news. Because the victor at most modern conventions has been a foregone conclusion, the notion of delegates as the final decision-makers in a long nomination process has been lost—but, under certain circumstances, perhaps this one, they may still have the final word.

Here’s a bit of history.

Between 1831 and 1972, presidential candidates were nominated in conventions composed of elected officials and party leaders. Primaries were an invention of the Progressive Era, but presidential primaries were few and far between—averaging, between 1932 and 1968, about 16 a year and, moreover, most of those primaries were non-binding, meaning they were “beauty contests” only and had little to do with the preferences of convention delegates.1 In other words, they were irrelevant. For example, in 1952, Tennessee Senator Estes Kefauver won 12 out of the 15 presidential primaries held that year, but his victories did not add up to delegates and he lost the nomination to Adlai Stevenson on the third ballot.

And then came the tumultuous 1968 convention which took place in the midst of protests against the war in Vietnam. Of the nine primaries that even listed the presidential candidates on the ballot, only three were in states where the primary results were binding when it came to delegate selection.2 Anti-war activists felt locked out of the party and were given, as a sort of consolation prize, a reform commission.

The reform movement in the Democratic Party that followed did two things, which were to radically change the nomination system—it required delegates to “fairly reflect” the presidential preferences of the voters that chose them—and it began the movement away from state conventions which selected delegates and toward primaries. Today, in both political parties, most states have a presidential primary, and delegates are selected to reflect the results.3

Implicit in the move to binding primaries (which happened in both parties) was the assumption that delegates would not be free agents—they would vote according to the results of the primary in their district or in their state. In other words, they would be “bound” to their candidate. In the modern era, this assumption has only come under serious attack twice—once in the in Democratic Party and once in the Republican Party.

In 1980, the Democratic President Jimmy Carter faced a very difficult re-election. He had presided over record high inflation and unemployment—a situation economists had thought impossible until then. The Iranian hostage crisis and the military’s failed attempt to rescue them was a major humiliation and he was running far behind the Republican nominee Ronald Reagan. His political weakness led Massachusetts Senator Ted Kennedy to run against him in the primaries. And even though Carter racked up a substantial delegate lead early on, Kennedy began to win some later primaries and decided to take the fight all the way to the convention.

That’s where Kennedy came up against what came to be known as “the robot rule”—Rule 11(H). It said that all delegates to the convention were bound “to vote for the presidential candidate whom they were elected to support for at least the first convention ballot, unless released in writing by the presidential candidate.”4 Furthermore the rule contained an enforcement mechanism—delegates who tried to vote for someone other than the person they were elected to represent “may be replaced with an alternate of the same presidential preference by the presidential candidate…”5 To take the nomination away from President Carter, Kennedy had to convince enough delegates to change this rule. The battle was fought over the summer of 1980. In the end, very few Carter delegates defected and voted against the rule, allowing Carter to clinch the nomination.

In 2016, the Republican Convention went through their own version of the “robot rule” fight. Donald Trump had won the most delegates by running up pluralities in a fractured field of candidates. As the convention opened, it became clear that many important Republicans had serious doubts about Trump and were skipping the convention. Senator Jeff Flake of Arizona, an anti-Trump Republican, told people he wouldn’t be there because he had to “mow his lawn.”6

As in 1980, those who showed up to attempt to deny Trump the nomination centered their strategy around a rule. This one (Rule 16) read “If any delegate…demonstrates support under Rule 40 for any person other than the candidate to whom he or she is bound, such support shall not be recognized.”7 What this meant in practice was the secretary of the convention could ignore the votes of the actual delegates on the floor and simply record the delegate preferences as they had emerged in the primaries—Robot Redux—if you will. Republican delegate Kendal Unruh of Colorado, one of the leaders of the Stop Trump movement, proposed that the rule be amended to include a conscience clause that would allow delegates to vote against Trump on the first ballot. Other activists formed a group called “Delegates Unbound,” and Curly Haugland, a national committeeman from North Dakota, argued in a book called “Unbound: The Conscience of a Republican Delegate,” that delegates should be free agents.8 Ultimately, the attempt to change the rule failed and Trump’s nomination moved ahead to victory.

In the eight years since the 2016 convention, Trump’s control over the Republican Party has solidified, and a challenge, including a fight over the role of the delegate, is unlikely. Not so for the Democrats, however. Following their contentious 1980 convention, the robot rule was quietly buried and replaced with the following—Rule 13 (J):

“Delegates elected to the national convention pledged to a presidential candidate shall in all good conscience reflect the sentiments of those who elected them.” [Italics are mine.]

There is no definition, nor is there any history about what constitutes “in all good conscience.” Few, if any, delegates to recent conventions have ever sought to test it. But if worries about President Biden’s ability to run and to serve continue to grow, along with fears of handing the presidency over to Donald Trump, some delegates may find themselves tempted to vote for someone else. It would not be surprising if this rule and the decades-long debate over the role of the delegate becomes relevant again.

-

Footnotes

- See Elaine C. Kamarck, “Primary Politics: Everything You Need to Know About How America Nominates its Presidential Candidates,” (Brookings Press, Page 20 – Table 1.2

- To maintain control of their convention delegations, powerful governors or senators would sometimes run for president as “favorite sons”.

- The Republican Party allows states to use a variety of systems for awarding delegates to candidates, while the Democratic Party only allows proportional representation.

- See, Elaine Kamarck, “Primary Politics: Everything You Need to Know About How America Nominates Its Presidential Candidates,” (Brookings Press, page 205).

- Ibid

- See, Elaine Kamarck, “Primary Politics: Everything You Need to Know About How America Nominates Its Presidential Candidates,” (Brookings Press, page 209).

- Ibid

- Ibid

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).

Commentary

Are convention delegates bound to their presidential candidate?

July 11, 2024