On March 17, China “restored” diplomatic relations with Gambia. The action immediately reverberated through Taiwan and was read as a warning about the future of relations between the two sides of the Taiwan Strait.

Over the past eight years, Beijing refused to establish diplomatic relations with any of Taiwan’s diplomatic partners to avoid creating political problems for the island’s president, Ma Ying-jeou, because he had accepted China’s formula for the conduct of cross-Strait relations. Tsai Ing-wen, who was elected president on January 16, is not willing to explicitly support the same formula. China’s Gambia move suggests that it will demonstrate its displeasure by further undermining Taiwan’s international position. Although Gambia is small gruel for China, the restoration of China-Gambia ties is a big deal psychologically for Taiwan—and China knows it.

Unfriending and re-friending

The “restoration” move was actually quite clever. Gambia was one of those countries for which China and Taiwan had competed diplomatically. It had had relations with Taiwan from 1968 to 1974, then with China until 1995, and then back to Taiwan. In 2013, it decided to abandon Taiwan for China and announced that it was terminating relations with Taipei. But Beijing did not take the bait. At that time, it was playing for bigger stakes by improving its ties with Taiwan directly rather than trying to marginalize it in the international community, and it did not want to hurt Ma Ying-Jeou politically. Technically, it was not “stealing” one of Taiwan’s diplomatic allies, but it could still signal that it would accommodate to a Tsai presidency only on its own terms.

Technically, it was not “stealing” one of Taiwan’s diplomatic allies, but it could still signal that it would accommodate to a Tsai presidency only on its own terms.

The victory of Tsai and the Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) in the January elections posed a dilemma for Beijing. It had the option of seeking a mutual accommodation with Tsai, and so continue the stability and cooperation that had emerged under Ma Ying-jeou. But given China’s belief that Tsai and her party intended to pursue legal independence, it saw a risk that Tsai might take advantage of its goodwill and not reciprocate. She gave a press interview five days after the election that optimists believed indicated she was open to accommodation. Beijing remained suspicious and declined to give Tsai the benefit of the doubt.

Instead, it has pursued the harder option of insisting that Tsai affirmatively accept its fundamental principles as a price for a continuation of the status quo, even though many of her supporters oppose such commitments. In effect, Tsai would have to choose between her political base and China. If she stuck with her supporters, Beijing would trigger a deterioration in cross-Strait relations—economically, politically, and diplomatically. Restoring relations with Gambia was one way for China to demonstrate that its hardball threats were not a bluff.

Restoring relations with Gambia was one way for China to demonstrate that its hardball threats were not a bluff.

Scylla and Charybdis

The Gambia action suggests a more fundamental implication: that China’s deliberate goal in imposing various sanctions is to increase the likelihood that Tsai’s presidency will fail. Hence, it creates the Hobson’s Choice between a deterioration in cross-Strait relations and preserving domestic political support, and goes beyond limited and symbolic “punishment.”

It knows perfectly well how to achieve mutual accommodation (in part because individuals from Taiwan and Americans have been offering ideas on how to do so). But that would be inconsistent with the goal of ensuring her failure. (If this indeed is China’s strategy, Tsai will have to make clear to the Taiwan public and to others that she did her best and that failure occurred because Beijing wanted it to occur.)

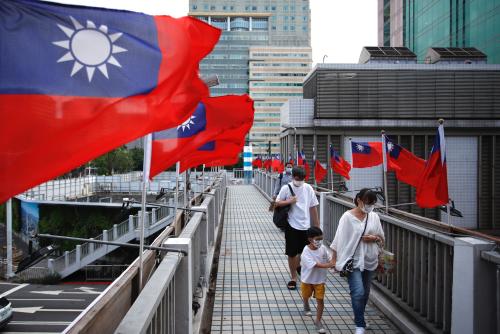

For Taiwan, having 22 diplomatic partners strengthens its government’s view that it is a sovereign entity. For the Taiwan public, the loss of those diplomatic allies feeds fears that Taiwan is slipping into vulnerable isolation and increasingly subject to Chinese intimidation. There is anxiety that other partners are ready to switch once Beijing gives them the green light.

The Obama administration, for its part, is urging both Beijing and Taipei to demonstrate patience, creativity, flexibility, and restraint. China’s Gambia move is a clear sign that it has a very different game plan.

Commentary

China’s Gambia gambit and what it means for Taiwan

March 22, 2016