On Oct. 8, California became the first state to require Ethnic Studies courses for students in order to graduate from high school. All California high schools must offer Ethnic Studies beginning in the fall of 2025, and all students must complete one semester starting with the graduating class of 2030. In signing the bill, Gov. Gavin Newsom acknowledged that “America is shaped by our shared history, much of it painful and etched with woeful injustice.” Students “must understand our nation’s full history if we expect them to one day build a more just society.”

This is long overdue. Ethnic Studies will help Californians understand how our past informs our present, including the surge in anti-Asian violence and hate during the coronavirus pandemic.

As fears about the coronavirus increased early last year, Asian Americans—and especially Asian American women—began to sound the alarm about a rise in anti-Asian violence, harassment, and hate. Asian Americans have been stabbed, beaten, pushed, spit on, harassed, and vilified based on the false assumption that they were to blame for the origin and spread of COVID-19.

But it took the mass murder of eight people—including six Asian women—working in three massage parlors in Atlanta to catapult anti-Asian violence onto a national platform.

Working low-wage jobs that required not only their physical presence but also their physical touch during a global pandemic, their lives laid bare the vulnerabilities at the intersection of race, gender, class, nativity, and citizenship.

The lives of the six Asian women massacred may seem distant and unconnected to mine, but as a woman, an Asian American woman, an immigrant, and a daughter of immigrant entrepreneurs, I know that my fate—and that of many others—is intimately connected to theirs.

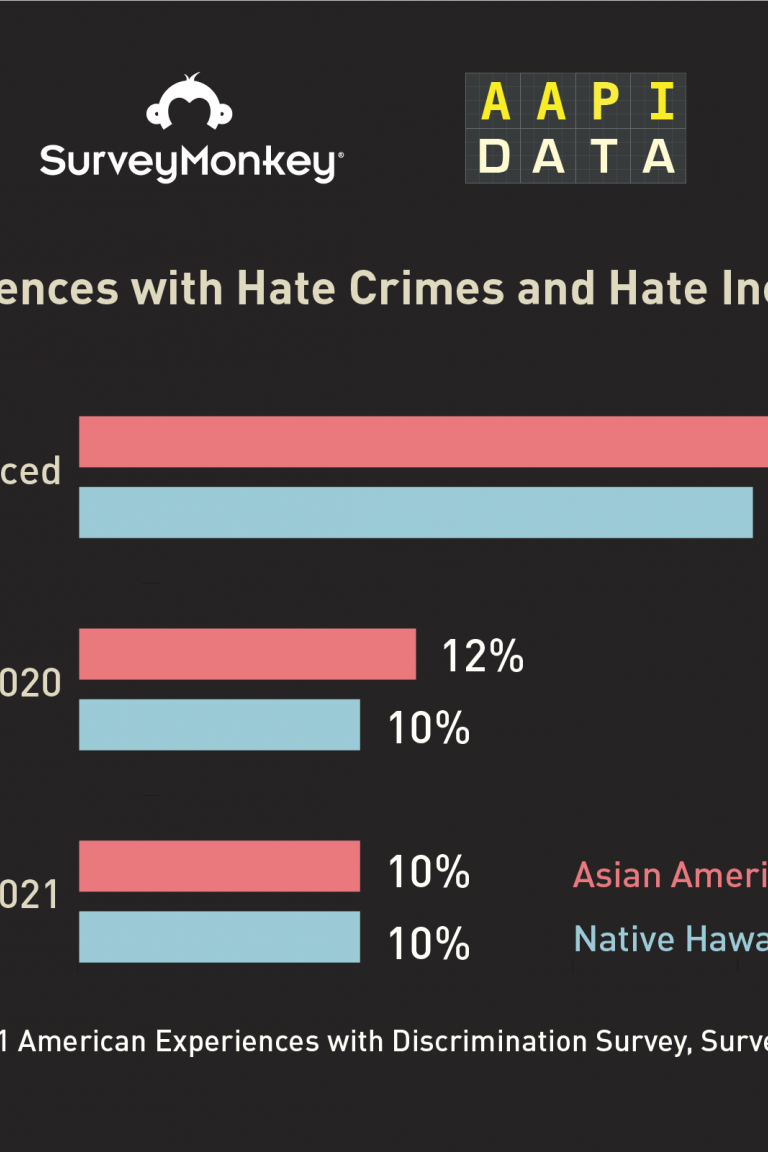

A national survey by SurveyMonkey and AAPI Data fielded immediately after the Atlanta massacre in March of this year revealed that since the onset of COVID-19, 1 in 8 Asian American adults has experienced a hate incident (Figure 1), and 1 in 7 Asian American women worry consistently about being victimized (Figure 2), revealing scars born from a legacy of anti-Asian bigotry, misogyny, and medical scapegoating that date back more than 150 years. This history is absent in most American high school textbooks and university curricula.

[Figure 1]

[Figure 2]

The 1882 Chinese Exclusion Act emerged from the lesser known 1875 Page Act, which prohibited the entry of unfree laborers, prostitutes, and women who were brought for “lewd and immoral purposes.” Proposed by Horace F. Page—a Republican congressman from California who exemplified his party’s stance toward Chinese women in the mid-1870s—the bill aimed to send “the brazen harlot who openly flaunts her wickedness in the faces of our wives and daughters back to her native country.” Page linked ethnicity and gender to disease and immorality in order to justify his argument for Chinese exclusion. Chinese women were characterized as “the most undesirable of population, who spread disease and moral death among our white population,” according to California Sen. Cornelius Cole.

Science and medicine were critical to the medical and moral scapegoating of Chinese women who were deemed invariably to be prostitutes. In his role as president of the American Medical Association in 1876, J. Marion Sims warned that syphilis had reached epidemic proportions in San Francisco because of the cheap sexual favors doled out by Chinese prostitutes to white men—and alarmingly, to white boys as young as eight.

Sims drew on the testimony of Dr. Hugh H. Toland who testified before the San Francisco legislature that Chinese prostitutes were spreading a unique strain of syphilis that failed to respond to therapy and proved deadly for his white patients. Toland claimed, “There is scarcely a single day that there are not a dozen young men come to my office with syphilis or gonorrhea… in nine cases out of ten it is the ruin of them,” adding that the “whole system becomes poisoned and debilitated.”

Apart from the medical threat, Toland underscored the moral threat posed by Chinese prostitutes to young, white boys:

“I have seen boys eight and ten years old with diseases they told me they contracted on Jackson Street. It is astonishing how soon they commence in indulging in that passion… I am satisfied, from my experience, that nearly all the boys in town, who have venereal disease, contracted it in Chinatown. They have no difficulty there, for the prices are so low that they can go whenever they please. The women there do not care how old the boys are, whether five years old or more, as long as they have money.”

White prostitutes far outnumbered Chinese prostitutes, yet they were not similarly vilified because according to the Chief of Police, “white women would not allow boys of ten, eleven, or fourteen years of age to enter their houses.” Moreover, “The prices are higher, and boys of that age will not take the liberties with white women that they do in Chinatown.”

While there was no evidence to support these statements, Mary P. Sawtelle published them nevertheless in The Medico-Literary Journal in 1878 in an essay titled, “The Foul Contagious Disease. A Phase of the Chinese Question. How the Chinese Women are Infusing a Poison into the Anglo-Saxon Blood.” These testimonies were reproduced for decades.

It is worth noting that Sims, Toland, and Sawtelle were noted pillars of white, liberal society: Sims is credited as “the father of gynecology”; Toland founded a Medical College in his name which he later transferred as a gift to the University of California, San Francisco; and Sawtelle was one of the first women on the West Coast to attend medical school, and also an early suffragist. Each used science and medicine to support claims about Chinese women as both medical and moral threats to White boys as young as ten, eight, and five.

Science and medicine are beginning to confront the shameful and painful aspects of its history, including the medical scapegoating of Chinese, the unethical surgeries performed without anesthesia on female slaves, and the promotion of eugenics in order to reduce “unfit” populations. Rather than ignoring this history, Ethnic Studies demands that we confront it—recognizing that we cannot understand the present nor guide a more just future if we do not reckon with the past. A new national survey from the American Historical Association reveals that the overwhelming majority of Americans support teaching history about the harms done to other groups even if it causes discomfort or feelings of guilt. California is leading the nation in this charge. It is time for the rest of the country to follow suit.

Commentary

Reckoning with science, medicine, and scapegoating

October 29, 2021