SpaceX’s successful launch on Saturday of a rocket carrying ten next-generation Iridium Communications satellites marks the latest chapter in the remarkable turnaround tale of Iridium, an engineering marvel whose 66 satellites can link any two points on the planet. Introduced with much fanfare in 1998 (Vice President Gore made the first call on an Iridium phone), Iridium went bankrupt in less than a year, and its parent company (Motorola), worried about future liability, came within hours of deorbiting the entire constellation. The federal government, by then a major user of satellite phones, quietly facilitated the acquisition of Iridium by private investors, who upended the business model and succeeded where Motorola had failed.

Since 2001, Iridium satellite phones have saved tens of thousands of lives and proved indispensable in war zones, disaster areas, and for hundreds of commercial and scientific uses in parts of the globe that are otherwise inaccessible. They were the only phones that worked in New York City on 9/11 and in New Orleans after Hurricane Katrina. And following the 2010 earthquake in Haiti, when 50 organizations arrived with their Iridium phones, it was clear that Iridium had become standard operating equipment for disaster relief workers worldwide. Iridium’s “netted” phones, which provide a “party-line” for soldiers in a unit on the move, have been called the most dramatic advance in combat communications since Motorola’s invention of the Walkie-Talkie during World War II.[1]

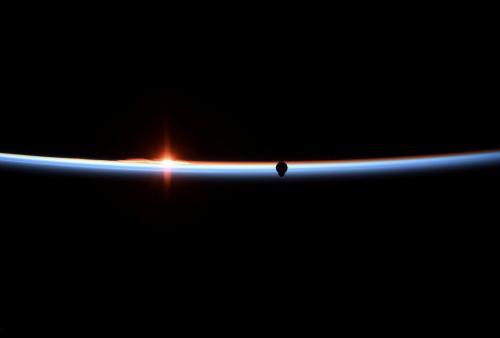

Having transformed remote telecommunications, Iridium is about to do the same for aircraft surveillance and air traffic control. As was made clear by the events following the disappearance in 2014 of Malaysian Airlines Flight 370, air traffic controllers today have only a rough idea of the location of an airplane flying in oceanic airspace. Iridium’s new satellites will be able to track airplanes in real time anywhere above the earth’s surface, allowing for safer and more efficient use of the 70 percent of global airspace that lacks radar-type surveillance. But while foreign air navigation service providers (ANSPs) have embraced what they see as a game-changing capability, the U.S. Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) has been non-committal.

Space-Based ADS-B

Iridium’s new technology has the ungainly title of space-based ADS-B, for Automatic Dependent Surveillance-Broadcast. ADS-B is an advanced surveillance technology that transmits an aircraft’s GPS position automatically to anyone with the appropriate receiver. The FAA has installed more than 600 ground stations to receive ADS-B signals and by 2020, aircraft operating in most U.S. airspace must be equipped with ADS-B transponders. Europe, Australia and other countries have imposed similar mandates for ADS-B equipage.

Although ground-based ADS-B represents a marked advance over radar, its coverage (like that of radar) is limited to the airspace over land. For the airspace over oceans and remote areas that cover more than 70 percent of the earth, ANSPs must rely on reports from the aircraft that are transmitted only every 15-60 minutes. Lacking precise positional information, ANSPs keep aircraft separated by 30-120 nautical miles—compared to the 3-5 nautical mile separations in airspace covered by radar or ADS-B—and they strictly control the route, speed and altitude that the aircraft must fly.

Thanks to advances in technology, Iridium’s next-generation satellites will receive the signals transmitted every few seconds by ADS-B-equipped aircraft. Because Iridium’s satellites can “see” the entire globe, ANSPs that subscribe to the service will be able to track the exact location of aircraft in areas outside the range of radar and ground-based ADS-B. A second satellite communications provider, Globalstar, also plans to offer space-based ADS-B services. Although Globalstar’s system (unlike Iridium’s) will require aircraft to install additional equipment and will lack complete global coverage, the potential for competition in the market for space-based ADS-B is highly desirable.

The most immediate benefit of space-based ADS-B will come from the ability to reduce the large separations between aircraft in oceanic/remote airspace, which will make it easier for aircraft operators to fly at their preferred speed and altitude. Canada’s ANSP, NAV CANADA, which manages much of the dense traffic on the North Atlantic, estimates that space-based ADS-B will save aircraft operators $800 per flight on average in fuel costs alone.

Reduced separations will also ease the bottlenecks created as aircraft transition from radar-controlled airspace into oceanic airspace—a leading cause of congestion at airports like New York’s John F. Kennedy and San Francisco International. By reducing the differential between radar and oceanic separations, space-based ADS-B can also make it easier for the FAA to divert planes from radar-controlled coastal routes blocked by bad weather out into oceanic airspace, thus avoiding delays that can propagate for hundreds of miles.

In addition to the obvious safety benefits, being able to track aircraft everywhere in real time will significantly improve search and rescue operations, such as the one for Malaysian Airlines Flight 370. If a commercial aircraft flying in oceanic airspace is reporting its position every 15 minutes, the search area is about 55,000 square kilometers; by contrast, with the 8-second update rate that space-based ADS-B will provide, that search area is only 4 square kilometers. The Department of Defense and U.S. intelligence agencies will also be able to take advantage of space-based ADS-B, including the ability to monitor global traffic flows in real time and more easily land military aircraft in war zones and disaster areas that lack air traffic infrastructure.

Whither the FAA?

The global organization representing ANSPs has said that space-based ADS-B can “revolutionize” air traffic surveillance, and many ANSPs are acting on that belief. In 2012, after the FAA declined to make an equity-like investment, NAV CANADA pledged $150 million to become a 51 percent owner of Aireon, the Iridium joint venture created to provide space-based ADS-B as a service to individual ANSPs. The ANSPs from Ireland, Denmark and Italy committed to an additional $120 million in equity, making Aireon 75.5 percent ANSP-owned, and another seven ANSPs, including the UK’s NATS, have signed long-term contracts. NAV CANADA and NATS plan to introduce the Aireon service in the North Atlantic in 2018.

Although it signed an MOU with Aireon to ensure that the system would meet U.S. requirements, the FAA has not committed to subscribe to space-based ADS-B. In part, this hesitation reflects a belief by some in the FAA that many of the benefits of reduced oceanic separations can be achieved through improvements in the current, position reporting technology (ADS-Contract, or ADS-C). The FAA asked an industry advisory group to compare the benefits case for space-based ADS-B versus ADS-C, and that much-needed analysis is underway.

The FAA’s non-committal stance on space-based ADS-B may have more to do with the agency’s highly constrained budget environment. The charge for space-based ADS-B is relatively modest (estimated to be in the tens of millions of dollars a year, depending on the geographic scope of the coverage). But because the FAA is funded through annual appropriations, it cannot pass that cost on to aircraft operators, as other ANSPs plan to do. Granted, aircraft operators pay indirectly for most of the FAA’s budget through taxes collected from passengers. However, FAA appropriations have been flat for five years and that trend is likely to continue. Under such a scenario, the FAA would directly bear the costs of space-based ADS-B whereas airlines would enjoy most of the benefits.

One solution to the budget dilemma is a shift to user-fee funding of the FAA. While the last several presidential administrations have proposed such a shift (and we argued for it in a 2008 Hamilton Project paper), Congress is unlikely to adopt it, at least in the near term.

Another approach would be for aircraft operators to pay for space-based ADS-B directly even though the service (i.e., data) would be delivered to the FAA. There is some precedent for this in the way that data communications between pilots and air traffic controllers is currently funded. To allay concerns that the FAA would not follow through with operational improvements (e.g., reduced separation standards), operators’ payments could be tied to concrete indicators of improved performance. However, even a performance-based payment scheme approach would face resistance from the major airlines, most of whom favor major structural change in FAA governance.

As another approach, the FAA could share the cost of space-based ADS-B with other federal agencies that would benefit significantly from the service (the Departments of Defense and Homeland Security and the intelligence agencies). Although cross-agency funding arrangements can be challenging, there is considerable precedent for them.

Conclusion

Most aviation experts believe that space-based ADS-B is a game-changer with the potential to transform the air traffic control landscape. The FAA’s failure to date to embrace this exciting new capability likely reflects the agency’s dire budget situation and inability to impose user fees. And while budgeting is necessarily about making tradeoffs, under the current FAA funding arrangement, there is a significant disparity between who would pay for and who would benefit from space-based ADS-B. Federal policymakers need to find a way to overcome that disparity so that it does not result in the loss of an opportunity that is highly net beneficial.

Dorothy Robyn is an independent policy analyst and Kevin Neels is an economist with The Brattle Group. Robyn and Neels are completing an independent (self-funded) economic analysis of space-based ADS-B. Robyn worked on policy issues involving Iridium as a member of President Clinton’s White House economic team.

[1] Investigative reporter John Bloom recounts the dramatic birth, near-death and rebirth of Iridium in his exhaustively researched new book, Eccentric Orbits: The Iridium Story, which the Wall Street Journal designated as one of the ten best non-fiction books of 2016.

Commentary

Warranted surveillance: SpaceX satellite launch holds promise for air traffic control

January 17, 2017