Chief Justice John G. Roberts, Jr. has designated two new members of the eleven-member Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Court (FISC), which Congress created in 1978 to act on government applications to undertake national security investigations, principally domestic surveillance. Congress directed the chief justice, alone, to designate sitting federal district judges to serve on the FISC for unrenewable seven-year terms, in addition to their regular judicial duties.

The FISC has been the object of debate about the costs and benefits of its largely non-adversary proceedings and its comparative secrecy. Some have also charged that its membership’s preponderance of Republican appointees and former prosecutors have made it less likely to question surveillance requests rigorously, and more likely to stress national security over privacy in overseeing the legality of surveillance activities.

Last June, I published a Lawfare Research Paper Series analysis of FISC’s composition from various perspectives and assessed possible links between designees’ appointing party and prosecutorial experience and FISC decisions. Such links are hard to establish. But optics are important to the FISC’s credibility; even if it is not ideologically oriented, it may appear so if it is dominated by appointees of one political party, or by former prosecutors.

My goal in this short post is not to rehash that comparatively lengthy analysis but rather, my objectives are to highlight some major aspects of the FISC’s composition when the two new designees become members next month and to update my previous comparison of the designees of Chief Justices Burger, Rehnquist, and Roberts.

The May 19, 2015 FISC compared to previous FISCS

On May 19, 2015, two Clinton appointees, one with slight, early-career prosecutorial experience, are due to join the FISC, replacing term-expired Reagan and Clinton appointees, both of whom had substantial prosecutorial/national security backgrounds. Compared to the 47 judges who served previously, the new FISC will:

- be as equally representative of all circuits as most previous FISCs, save for the over-representation of the District of Columbia circuit due to the statutory requirement that three members live within 20 miles of the capital;

- have a slightly greater proportion of Republican appointees—eight of 11 versus 66 percent of previous designees;

- have about the same proportion of former prosecutors (broadly defined) —six of the eleven versus 66 percent of the previous designees (according to biographical data on the Federal Judicial Center’s History of the Federal Judiciary website at http://www.fjc.gov);

- have about the same proportion of long-time former prosecutors—two of the eleven versus 15 percent of the former designees (defining “long term as ten or more years);

- have no former public defenders, versus five among the previous designees;

- have had somewhat more judicial experience at the time of designation—four of the eleven had 20 or more years on the bench when designated, versus 15 percent of the previous designees, while three of the current FISC had ten or fewer years of experience, versus 34 percent of the previous designees;

- have had about the same number in senior status when designated—three of the 11 versus 31 percent of the previous designees (senior status is a form of semi-retirement in which judges might not carry a full caseload);

- have proportionately more women—three, compared to four among the previous 47— and about the same proportion of African-Americans (none versus three among the previous designees).

Comparing designees of Chief Justices Burger, Rehnquist, and Roberts

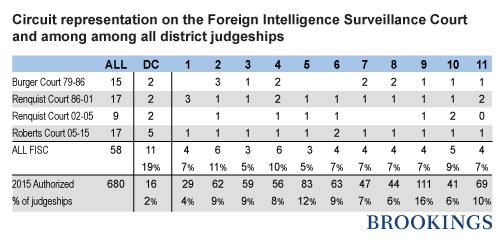

Circuit Representation

The 1978 statute directed that the FISC’s then-seven judges each come from a different circuit. In 2001, Congress enlarged the FISC to 11 judges but kept the minimum number of circuits represented at seven and imposed the requirement concerning the District of Columbia. Rehnquist and Roberts have spread the designations broadly among the non-D.C. circuits.

There is no requirement that circuit representation on the FISC mirror representation among authorized judgeships, and it does not. Beyond the D.C. circuit’s oversized membership, five circuits (First, Second, Fourth, Eighth, and Tenth) have contributed proportionately more to the FISC than to the national pool of 680 authorized judgeships, while the Third, Fifth, Sixth, Ninth, and Eleventh have been underrepresented. Most differences are slight, although the Fifth and Ninth circuits’ representations nationally are more than twice that of their FISC representation.

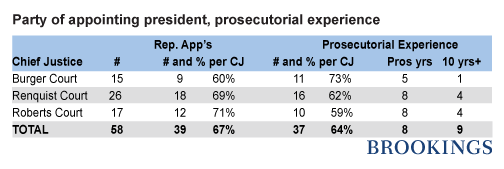

Party-of-Appointing President, Prosecutorial Experience

This table shows the breakdown of designees as to appointing president’s party and designees’ service as state or federal prosecutors; the median number of years that those judges had been in prosecutorial positions; and the number serving at least ten years in those positions (a somewhat arbitrary cut-off to eliminate, for example, judges who spent a short time after law school in the state’s attorney’s office). It should be noted that the small numbers caution against expansive inferences.

The proportion of Republican appointees has been increasing—from 60 percent of Burger’s designees to 71 percent of Roberts’. President Reagan’s appointees have dominated the FISC—13 judges, almost a quarter of the total—followed by eight each of Nixon’s and Clinton’s, six W. Bush appointees, and five or fewer for other presidents. Johnson (two) and Obama (one, to date) have the fewest designees.

The proportion of Republican appointees has been increasing—from 60 percent of Burger’s designees to 71 percent of Roberts’. President Reagan’s appointees have dominated the FISC—13 judges, almost a quarter of the total—followed by eight each of Nixon’s and Clinton’s, six W. Bush appointees, and five or fewer for other presidents. Johnson (two) and Obama (one, to date) have the fewest designees.

The proportion of judges with prosecutorial experience has declined from 73 percent of Burger’s designees to 59 percent of Roberts’. The eleven former prosecutors whom Burger designated had been in those positions a median of five years, a figure that went up slightly for both Rehnquist’s and Roberts’ designees. For those who had been prosecutors for ten years or more, the proportions have increased, from one of Burger’s eleven ex-prosecutor designees to four of Roberts’s ten.

Of the 37 former prosecutors, 12 went on the district court immediately, or very shortly, after the prosecutorial service. The median time from the end of prosecutorial service to FISC designation has declined—30 years for Burger’s ex-prosecutors to 26 for Rehnquist’s to 18 for Roberts’.

FISC judges with experience as public defenders or in the Judge Advocate General’s Corps have been infrequent—three former JAGs and five former public defenders, only one of whom, a Rehnquist designee, had served as a public defender for more than ten years.

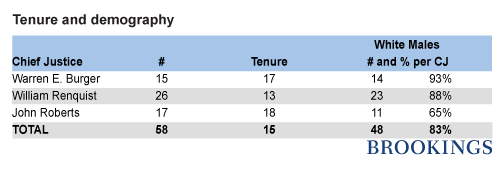

Tenure and Demography

This table shows the median number of years each chief justice’s designee had served on the district court when designated and the proportion of white males among their designees.

FISC judges’ district judge tenure at the time of designation has varied. The median time for Burger’s designees was 17 years versus 13 years for Rehnquist’s and 18 for Roberts’, but Roberts’ 17 designees also include the two with the shortest Article III service when designated—4.2 years for his first designee and 3.2 for his 2014 designee.

FISC judges’ district judge tenure at the time of designation has varied. The median time for Burger’s designees was 17 years versus 13 years for Rehnquist’s and 18 for Roberts’, but Roberts’ 17 designees also include the two with the shortest Article III service when designated—4.2 years for his first designee and 3.2 for his 2014 designee.

Demographic diversity has not been a major point of contention as to the FISC. That said, the proportion of white males has declined steadily—from almost all of Burger’s designees to 65 percent of Roberts’—due at least in part to the increase in diversity in the judiciary generally. The three women currently on the FISC represent almost half of the seven women designated since 1978. Each chief justice has designated one African-American district judge.

Change the designation responsibility?

Several legislators have proposed broadening FISC designators beyond the chief justice. I said in my 2014 analysis, cited above, and still believe that “Congress must first convince itself that the current process is sufficiently problematic—and incapable of self-correction—as to merit a major change.”

Commentary

Changing composition of the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Court: New designees

April 16, 2015