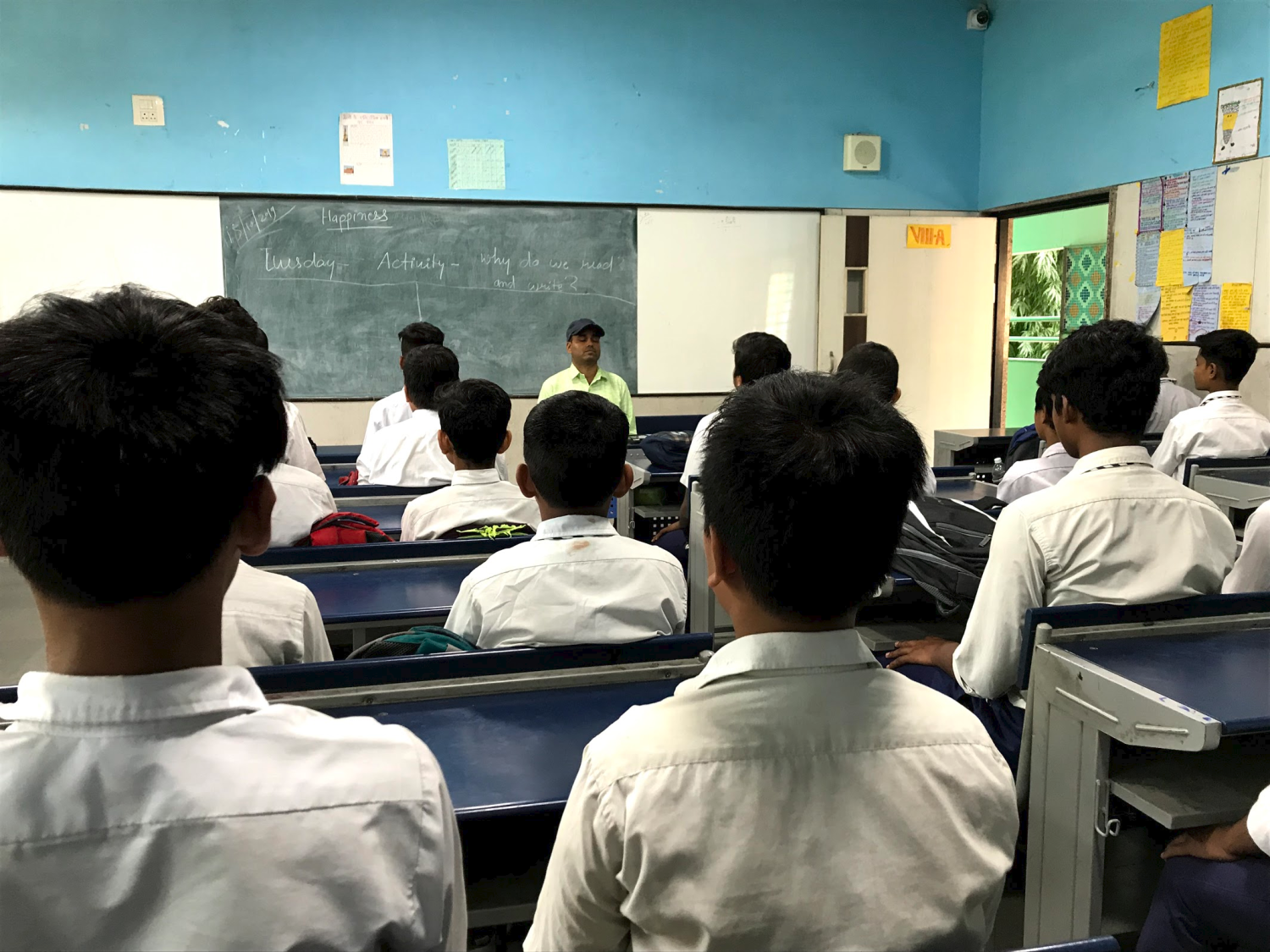

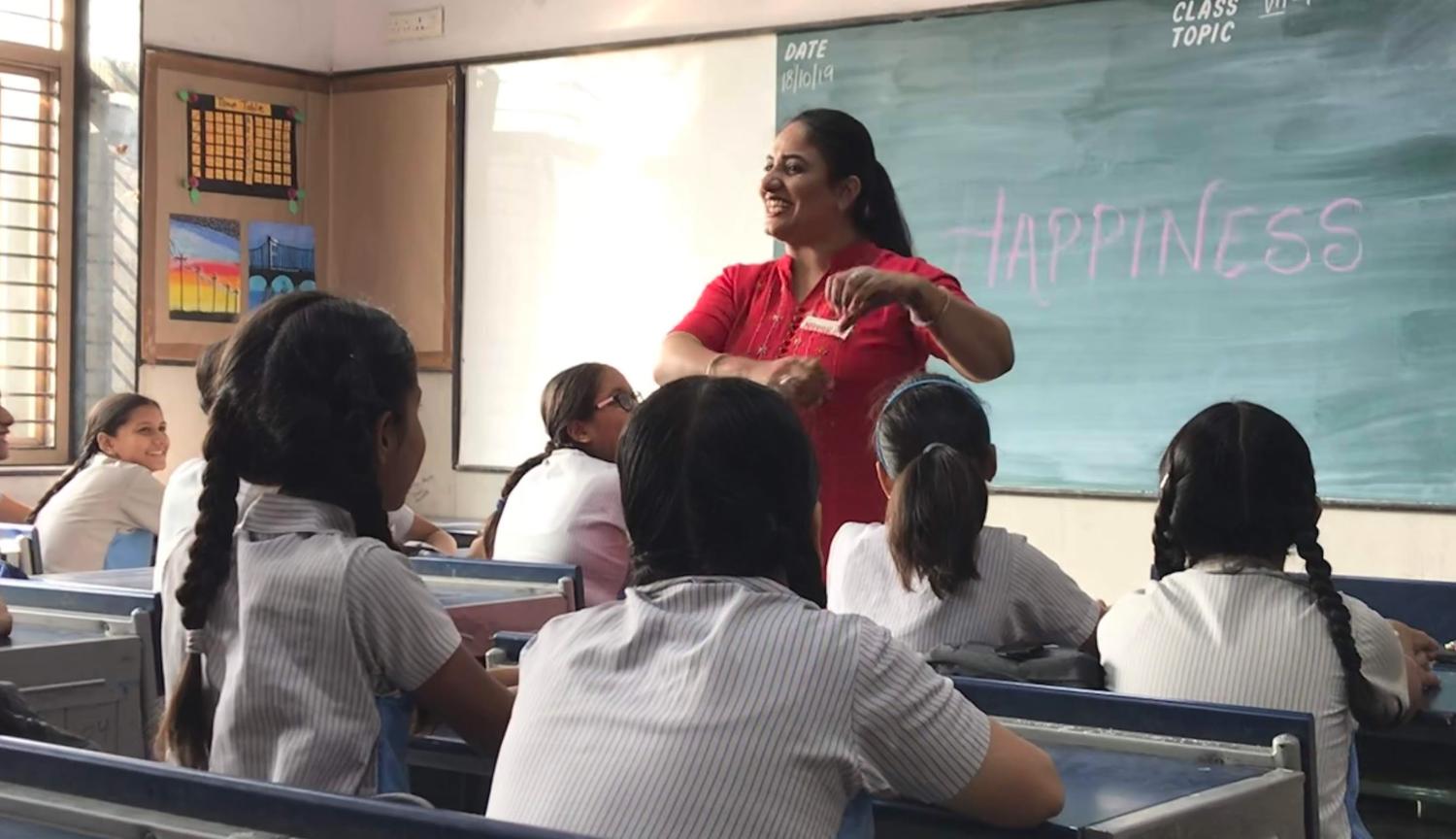

“Take a deep breath. Release. Take a deep breath. Release. Concentrate on the noises coming from the environment. What do you hear? Slowly, focus on your own breathing.” A grade 7 teacher at Rajkiya Pratibha Vikas Vidyalaya in Delhi, walks her students through a breathing exercise. After three minutes, she says, “When you are ready, start moving your toes; start moving your fingers; now, slowly, open your eyes.” This is a typical morning in happiness class.

Education systems around the world are facing challenges in preparing students to deal with the demands of unpredictable environments. Specific to India, children growing up in adverse circumstances and coming into the school system as first-generation learners don’t have the foundational capacities to learn and engage in the classroom. Moreover, depression is a serious issue among youth, with an increasing number of suicides each year. In addition, the World Happiness Report, 2019 ranked India 140 out of 156 countries. In response, the Delhi government launched the happiness curriculum in all 1,030 government schools from kindergarten through grade 8 in July 2018. In line with the vision for India’s education system as well as the Sustainable Development Goals (SDG-4), the implementation of the curriculum is a landmark first step in expanding a formal, public education system to focus on the holistic development of all learners, invest in their well-being, and improve the overall quality of education.

The development of the curriculum began with one question: What makes a good life? Traditionally, education has been oriented toward making a living, but it does not teach students how to make a good life and contribute to society. The Delhi government set out to solve this problem, and approximately 40 total teachers, in partnership with four NGOs, were chosen to write a curriculum that would develop “emotionally sound students.” Before writing the curriculum, the teachers were trained in what is known as “Madhyasth Darshan” or “coexistential thought,” which is based on understanding all aspects of life, including spiritual, intellectual, behavioral, and material. According to this philosophy, life satisfaction and happiness can be achieved by being aware of the self, body, family, society, nature, and universe in order to live in harmony. However, while the Madhyasth Darshan program is designed for adults, the nonprofit Dream a Dream trained the mentor teachers to work with children using contextualized empathy-based pedagogies and a life skills approach for children. This philosophy permeates the happiness curriculum to address the learners’ emotional and mental needs by creating a stimulating environment through mindfulness, critical thinking, storytelling and experiential, play-based activities. In the happiness classes, it is not about being right or wrong; it is about allowing students to express themselves, without judgement. Teachers are not required to finish the syllabus, but rather, to ensure that all children internalize and understand the concepts taught and have the opportunity to participate.

Sound too good to be true? Are the students happier because of the happiness curriculum? That’s the question that is on the minds of the Delhi government, curriculum developers, happiness coordinators, teachers, and parents.

The happiness project

Over a nine-month period, the Brookings Institution is partnering with Dream a Dream to develop measures that can assess the happiness curriculum by looking at whether there are changes in teacher and student behaviors attributable to the curriculum—a first step to evaluating its effectiveness.

The goals of the project are:

1. to understand and identify the factors that contribute to happiness;

2. to develop measures that capture teacher and student behaviors associated with the factors that contribute to happiness; and

3. to analyze the curriculum to identify the expected standards regarding teacher and student behaviors.

Recently, the Brookings and Dream a Dream teams were in Delhi to get a more complete picture of the curriculum. They spent five days visiting schools, observing happiness classes, talking with developers of the curriculum, and meeting with the Minister of Education, as well as engaging in focus group discussions with mentor and classroom teachers, happiness coordinators, and students.

So far, teachers and students are noticing changes, not only in happiness classes, but also in other classes. According to one teacher, he feels that “students are becoming more inquisitive and are asking questions…the happiness class removes the hesitation of the students. The happiness class has improved the student-teacher relationship, so when it comes to other subjects, students are more comfortable opening up in class.” Students are also recognizing a change, especially when it comes to mindfulness activities, similar to the one described above—“it makes me feel different…my mind gets refreshed, and it helps me concentrate on the particular subject even if I am not interested.”

Despite the positive anecdotes, the happiness curriculum raises many more questions than answers for the government: “What kind of questions should we be asking? What can we expect to achieve with the curriculum, and can the approach achieve it? How effectively is the curriculum being followed? Are there differences between students who learn this curriculum and who don’t? Are there changes happening in the happiness classes compared to the other classes? Is that behavior transferring to other aspects of students’ lives?” Although we may not learn the answers to all of these questions, everyone involved views it as a long-term approach that will take much longer than a year or two to see changes. This project is an opportunity to learn about what works well and what does not, so that improvements can be made along the way.

Note: Vishal Talreja is co-founder and Sreehari Ravindranath is associate director – research and impact of Dream A Dream Foundation, which provides financial support for Brookings.

We would like to thank Swati Chaurasia, Amit Kumar Sharma, and Khushboo Singh from Dream a Dream and Aynur Sahin from the Brookings Institution for their contributions to this blog.

Commentary

How do you measure happiness? Exploring the happiness curriculum in Delhi schools

November 13, 2019