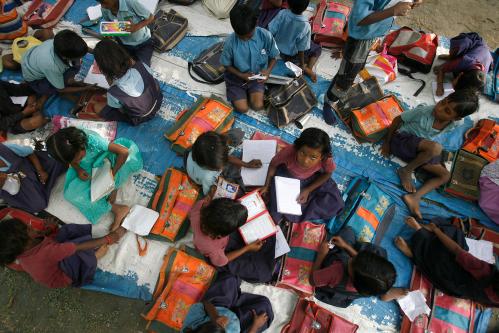

Despite considerable evidence of the many social and economic returns from secondary school, too few girls and boys continue their education beyond primary school; for those who do, many are not learning the skills they need for their future lives and livelihoods. In far too many countries, secondary school and other forms of post-primary education are not adequately providing young people with higher-level skills and competencies to participate in the 21st century’s knowledge-based economy.

Historically, in many low- and middle-income countries, secondary education has been primarily academic in nature, aiming to prepare only the youth of the small, elite classes for higher education. In sub-Saharan Africa, only 7 percent of young people in secondary school will go on to attend a university—and only 5 percent of girls. In other countries, secondary school has been used primarily to prepare young people for government jobs, of which fewer are now available as many public sectors shrink. Meanwhile, vocational and technical education—which often is regarded as path of last resort—has traditionally focused on training young people in a specific vocation. This narrow focus limits job opportunities and threatens livelihoods because job-specific skills quickly become obsolete in today’s rapidly changing world. Moreover, in many low-income countries, vocational training has also remained largely a provision for boys, leaving millions of girls with few options in their post-primary years. In sum, the few young people who are able to attend post-primary programs are not leaving prepared enough for either jobs in-demand or for higher education and training.

This issue of relevant skills building for tomorrow’s jobs is particularly relevant today as we face economic crisis and high levels of youth unemployment worldwide: Nearly 75 million youth are unemployed around the world and rates are even higher for young women. The highest rates are in the Middle East and North Africa, which have an 25 percent overall youth unemployment rate and 30 percent female youth unemployment rate. Not far behind is sub-Saharan Africa, where in 1 in 5 young people are not employed. Growing discontent from youth around the world, publicized by the Arab Spring, European protests and Occupy Wall Street, is occurring against the backdrop of a demographic explosion of the school-age population. Today, there are more young people ages 12-24 than ever before. Of the 1.5 billion young people in this age group, 1.3 billion live in developing countries, creating a “youth bulge” in developing country demographics.

Not surprisingly, the current post-2015 development agenda consultations on education and growth and employment are focused on skills, livelihoods and jobs. Based on the Center for Universal Education’s Global Compact on Learning, it is clear that for a post-2015 development agenda to have a transformative impact in relation to education for life skills and healthy, safe and dignified livelihoods, the following three actions need to be championed:

-

- Strengthen the link between post-primary education and improved life and labor opportunities. Too often there is a weak link between post-primary education, including vocational training, and the local labor market. As a result, young people are ill-prepared for the job opportunities available to them, which in many developing countries are in the informal economy, including subsistence farming, small-scale construction and informal trade. In order to help adolescents meet the challenges of the 21st century and develop into productive, responsible citizens who are well-equipped for healthy lives and work, the learning outcomes of post-primary education in most developing countries need to be reviewed. Moreover, there is a need for training teachers, health care workers and others professionals who are in short supply but are urgently needed in many developing countries. Schools and non-formal programs can do this through partnerships with local businesses, chambers of commerce and other relevant actors in establishing skills standards and developing demand-driven curricula.

-

- Focus on transferable skills. Secondary school and post-primary education should overcome the historical academic-vocational divide and move from purely academic or occupation-related skills to building a range of basic skills and “core competencies” needed to produce flexible, adaptable, multi-skilled and trainable youth prepared for employment in both the formal and informal economy. The labor market today is demanding workers who have strong critical thinking and interpersonal skills, such as communications, collaboration and strong work ethics. Some new subject areas and practical skills are increasingly in demand. Information and communication technology (ICT) is the fastest growing industry in the world, providing a wide variety of job opportunities. Young people must have early access to ICT training, including computer literacy, in order to take advantage of these opportunities. Proficiency in an international language, such as English, can also be important in expanding employment opportunities. Financial literacy is another important skill, particularly for girls and young women.

-

- Facilitate school-to-work transition. Linking post-primary education and skills training directly to local work is necessary to improve graduates’ employment and higher education prospects. Traditional apprenticeships and on-the-job training is often the most successful route to skills development, especially in preparing young people for work in the informal economy. Possible strategies include establishing career counseling or community-based seminars on livelihood options, including in the informal sector; creating business networks; mainstreaming entrepreneurial education in the school curriculum; and expanding access to financial services.

In addition to these three actions, the international community must work together to identify internationally comparable targets and metrics. Indeed, both the education and growth and employment consultations are currently seeking recommendations on indicators and metrics for measuring outcomes in light of improving skills development for livelihoods. Indicators are critical: We can’t improve what we don’t know. As of now, no internationally comparable indicator exists for youth skills and livelihoods. Within these discussions on the post-2015 development framework, there is an opportunity to identify internationally comparable skills that young people need for life and work and how best to measure them. The global Learning Metrics Task Force has highlighted the need to move beyond literacy and numeracy to social and emotional, cultural and physical well-being, communication, cognition, and science and technology skills, and the task force is currently determining the best approaches for measuring these skills.

The international community also needs to build the evidence base about what works, how it works and why it is working, particularly in the non-formal sector. There is a weak research base from which to evaluate successful youth skills building programs and identify models for wide scale replication. For instance, an analysis of the Youth Employment Inventory from the World Bank, International Labor Organization and UN’s Youth Employment Network revealed that only 23 percent of youth employment programs show evidence of net impact. Overall, there are too few rigorous evaluations and too little information on the short- and long-term impact of skills training and relative cost-benefit—either in formal or non-formal education. Moreover, data is often not disaggregated by gender and other factors of marginalization.

Whatever framework emerges from the post-2015 development discussions, it is clear that much more attention must be focused on ensuring young people transition to post-primary education while simultaneously addressing serious concerns about the applicability or relevance of what they learn to their current and future lives. We know that business as usual will not suffice. Alternative, flexible models that utilize innovative modes of delivery must be tested and more rigorous evaluations are required, particularly of non-formal programs. Reform must not only focus on academic skills but also ensure that children are learning the context-specific and health-related skills needed to thrive in the 21st century. These innovations are particularly crucial for poor girls given the high social and economic benefits of secondary school for these girls and their families and communities—and given the extremely low number of girls transitioning to post-primary school in many low- and middle-income countries.

Commentary

How the Post-2015 Agenda can have a Transformative Impact on Life Skills and Livelihoods

February 8, 2013