Throughout the months of May and June, millions of young Americans will cross the stage and toss their caps as they graduate from high school and college. As these young people begin to look ahead toward their futures in the workforce or in continued education, we’ve highlighted select pieces of Brookings research to help recent graduates understand their job prospects, income expectations, and more.

For high school graduates

A challenging labor market

After graduating from high school, many young adults face a tough transition into the working world. A study from Martha Ross and Natalie Holmes finds that 17% of all 18–24 year-olds, or 2.3 million young people, are out of work in America’s largest cities. Nationally, a total of 5 million are not working. High school graduates make up the large majority of this group, while only a small fraction of young people with a bachelor’s degree remain jobless.

Risks of automation

As the IT era transforms into the AI era, the emergence of powerful digital technologies that are capable of automating routine tasks will leave occupations that don’t require a bachelor’s degree more than twice as exposed as those that do. As research from Mark Muro, Robert Maxim, and Jacob Whiton shows, occupations like machine operators, food preparation workers, and payroll clerks are just a few of the jobs that workers can obtain without a college education but that face a very high automation potential.

How to find a good job without a degree

Those bleak pictures aside, for young people without a college degree looking to get ahead, research from Alan Berube, Chad Shearer, and Isha Shah points to three clear pathways into the middle class. The first involves switching occupations: Three-quarters of non-college workers who are projected to have a good job in 10 years begin their working lives in “starter fields,” such as retail and food service, and eventually move into better-paying careers, such as construction and maintenance. Second, industry matters. Industries like utilities, manufacturing, and government offer good and promising jobs for workers without a college degree. And last, living in the right city can help. For example, non-college manufacturing workers in Tucson, Arizona, are nearly twice as likely to have a good job as their counterparts in Stockton, California.

Interested in getting into tech?

A surprisingly large share of classic tech jobs—as many as half a million— are quite accessible to workers without a bachelor’s degree, as research from Mark Muro, Jacob Whiton, and Patrick McKenna shows. The sector’s need for talent and specific technical skills is a genuine opportunity for non-college workers with a passion for tech, especially in non-coastal cities like Springfield, Illinois and Bloomington, Indiana.

For college graduates

The most educated generation

As the first young adults of the “post-millennial” generation (born in the late 1990s and early 2000s) begin to graduate from college, they will follow in the footsteps of one of the most educated generations to date. More than a third of today’s millennials, or 25–34 year-olds, obtained a college degree by 2015, up from less than 30 percent of similarly aged adults in 2000 and not quite a quarter in 1980. Though college attainment has risen for all racial and ethnic groups, Hispanic and black millennials have fallen far behind their Asian and white counterparts.

Where are all the educated young people?

For college graduates looking to surround themselves with other degree-holding young people, they can look no further than a few key cities, Bill Frey explains. Topping the list is Boston, where nearly three out of five millennials—58 percent—are college graduates. But cities like Madison, San Jose, San Francisco, Washington, D.C., and New York aren’t far behind, each boasting at least 45 percent of millennials with degrees.

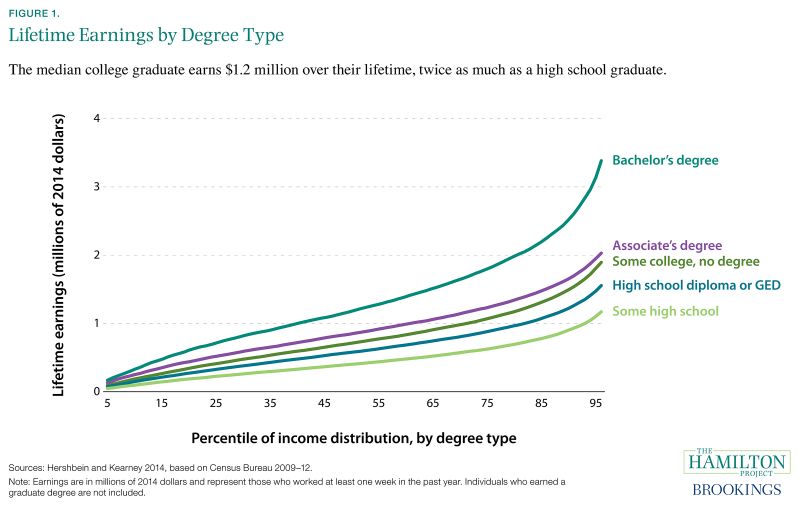

It was all worth it

As they transition into the workforce, many saddled with debt, today’s college graduates might be wondering: Was it worth the investment? The good news is most research points to yes. The typical bachelor’s degree holder earns about $1.2 million over a lifetime—about $600,000 more than the average high school diploma holder and about $300,000 more than the average associate’s degree holder. As Ryan Nunn explains for the Brookings Cafeteria podcast, college graduates also have nearly half the unemployment rate, lower mortality rates, and higher levels of well-being compared to high school graduates.

Find the highest-earning job for your major

Whether they studied business, psychology, nursing, or just about anything else, college students transition into a wide variety of careers. Only 14 percent of microbiology majors, for instance, go on to become a doctor—the most common job for that major. This diversity of career paths means that students who studied similar subjects may go on to have wildly different incomes. In this interactive report from the Hamilton Project at Brookings, you can explore the most common jobs and incomes for your college major based on your age and gender.

Thinking about graduate school?

For new bachelor’s degree holders considering a Ph.D. in the humanities, you may want to think again. As Dick Startz points out, in 2017 there were 340 tenure-track job openings for the 1,150 new historians who earned their Ph.D. that year. By contrast, there were 2,650 new jobs in economics for just 1,250 new Ph.D. economists. Furthermore, the average salary for the new humanities and arts Ph.D.s who do find a job is about $52,000 a year, lower than the average bachelor’s degree salary among 30–35 year-olds.

For undergraduates thinking seriously about going back to school, they’ll want to understand some of the trends about graduate student borrowing. As research from Adam Looney and Vivien Lee shows, the amount that graduate students are borrowing from the federal government is rising rapidly in the United States, reaching levels far above historic norms. While graduate students at public and private institutions are borrowing the largest amounts, students who attend for-profit institutions are the most likely to default on their debts.

Commentary

Congratulations, you graduated! Now what?

May 23, 2019