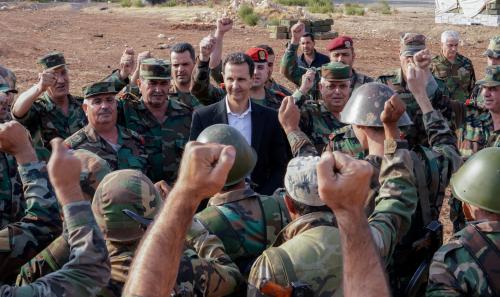

In March 2011, Syrians took to the streets demanding dignity and an end to endemic corruption. Bashar Assad’s regime responded brutally, quickly turning civil unrest into an all-out war that has been ongoing for nearly 11 years. For almost as long, international actors have claimed there can be no military solution to the conflict. Even as the military balance on the ground has shifted, efforts to negotiate a political settlement have lurched along, with nothing to show for years of United Nations-led mediation between the Assad regime and the opposition.

Undermined by the recalcitrance and obstructionism of the Assad regime, the so-called Geneva process has become little more than zombie diplomacy, kept alive not by any expectation that it will produce a result but by the absence of alternatives and the reluctance of the United States and European Union to let go of the only negotiating framework accepted by all members of the U.N. Security Council. Every month, the U.N. special envoy for Syria, currently veteran Norwegian diplomat Geir Pedersen, updates the Council in terms that have become as repetitive as they are predictable: We have made no progress, but opportunities remain to be explored.

Pedersen’s cautious optimism is laudable. Yet however modest his aspirations, there is no longer any meaningful opportunity to salvage the Geneva process. Russian officials have expressed frustration that they have not been able to wring a more accommodating posture out of their client in Damascus. Simultaneously, regional states have begun a gradual process of normalization — establishing diplomatic ties to the Assad regime and initiating discussions about bolstering trade and investment — that has further diminished whatever incentives might have existed to prod Assad into taking the Geneva process seriously.

To be sure, the Geneva talks have faced daunting odds from the outset. In December 2015, two months after Russia’s military intervention to rescue Syria’s dictator, the U.N. Security Council adopted Resolution 2254 calling for fair elections, a new constitution, and credible, inclusive, and non-sectarian governance. The resolution was, and remains, the most promising basis for a political settlement that is more than a fig leaf legitimating the status quo.

In line with the spirit of that resolution, Pedersen’s predecessor from 2014 to 2018, Staffan de Mistura worked to move intra-Syrian talks toward an encompassing agreement on four baskets: a credible non-sectarian transitional government; a future constitution; U.N.-supervised elections; and support for anti-terrorism efforts within Syria.

Despite reservations, opponents of the Assad regime agreed to de Mistura’s framework and participated in the talks in good faith. Assad, however, was never interested in any part of the political process. He once described Syria’s membership in the U.N. as “a game we play.” As the impact of Russia’s military intervention became more apparent, regime negotiators turned the process into a farce. Nor did Russia’s military support for Assad translate into political leverage. Even as Russia committed itself to the survival of Assad and his regime, it invested political capital in a diplomatic process it viewed as the pathway to an internationally accepted political settlement that would, in turn, make possible an easing of sanctions and access to funds for reconstruction. Yet Assad’s dependence on Russia notwithstanding, he has consistently treated the Geneva process with derision, refusing to play along — an object lesson in the ability of weak clients to resist pressure from influential patrons.

De Mistura labored on, but as the regime’s military position improved, Assad and his Russian backers lost interest in negotiating the meaty issues of political transition and early elections, narrowing the Geneva process to the matter of constitutional reform. Even so, it took 18 months after the establishment of a “constitutional committee” before talks once again got underway, with Pedersen as the U.N.’s special envoy.

Since its formation, the committee has met in Geneva six times without meaningful progress. From its inception, Assad’s delegates have succeeded in derailing, stonewalling, and otherwise undermining the talks. Russia has occasionally attempted to pressure Assad to take the process more seriously, to no avail.

Assad’s intransigence is paying off, as it has so often in the past. Recently, Moscow seems to have given up on Geneva entirely. Last month, Russia’s presidential envoy for Syria, Alexander Lavrentiev, said, “If somebody pursues the aim of creating a new constitution for the sake of changing the powers of the president, and thereby trying to change power in Damascus, this road leads nowhere.” Shortly after this statement, Ibrahim al-Jebawi, one of the 50 opposition bloc members of the constitutional committee, announced his withdrawal in a televised interview. He later stated that the Russian envoy’s statement “assured my previous convictions and let me withdraw,” further adding that he now considers the committee worthless.

What is painfully clear from both Russian and Syrian regime statements is the belief that Geneva is no longer needed as a pathway to normalization for the Assad regime. Overtures to Damascus from Arab capitals won’t confer legitimacy on Assad. Nor will they bring sanctions relief or Western support for reconstruction. Yet as normalization creeps forward — and if and when Syria’s full membership in the Arab League is restored — the Assad regime might be well on its way to international acceptance, its culpability in war crimes and crimes against humanity be damned. Russia will then be able to breathe a bit easier knowing it will not be stuck in the lead role of shoring up a critically unstable pariah regime.

If the Geneva process was always an exercise in the power of hope over experience, it has now been reduced to an empty shell, a form of zombie diplomacy that should be put out of its misery. Ending the process, however, does not mean that the U.N. will become merely a bystander in efforts to respond to the mass violence perpetrated on civilians by the Assad regime. In its place, the U.N. should invest more heavily in the work of the mechanisms it has created to pursue accountability for perpetrators of war crimes in Syria, especially the International, Impartial, and Independent Mechanism established by the General Assembly for this purpose. It should also seriously consider the formation of an additional mechanism focused on the fate of the hundreds of thousands detained and missing, mostly at the hands of the regime but also by extremist armed groups.

The end of Geneva would permit Syria’s opposition to turn its attention to institution building and improving governance in areas outside of regime control. Shifting its focus in this way will improve the opposition’s legitimacy among international backers and, more importantly, in the eyes of the disgruntled and impoverished population it claims to represent.

For their part, the U.S., EU, and other international actors should continue to support Resolution 2254, maintain current sanctions policies, more actively work to prevent normalization of the Assad regime, encourage judicial processes under the principle of universal jurisdiction, and support Syrians in areas outside regime control to help them rule themselves more sustainably.

What ending the Geneva process will do, therefore, is shift the landscape of Syria diplomacy. Such a step would remove a framework that has become a counterproductive obstacle to progress. It would move to the fore alternative means for the U.N. and other actors to shape the outcome of the Syrian conflict, provide a measure of justice to victims of the regime, and contribute to the longer-term stability and security of the Syrian people.

Commentary

Zombie diplomacy and the fate of Syria’s constitutional committee

January 24, 2022