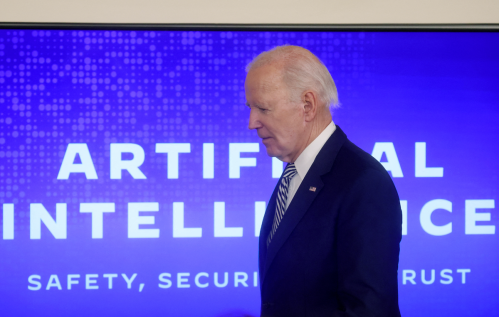

On October 30, 2023, President Biden signed an Executive Order on the Safe, Secure, and Trustworthy Development and Use of Artificial Intelligence. The Executive Order (EO) features eight guiding principles—new standards for AI safety; protecting Americans’ privacy; advancing equity and civil rights; standing up for consumers, patients, and students; supporting workers; promoting innovation and competition; advancing American leadership abroad; and ensuring responsible and effective government use of AI—and charges federal agencies with both drafting guidelines for responsible AI and taking steps to regulate and review its applications. The EO also builds on prior AI guidance, such as the White House’s national Blueprint for an AI Bill of Rights and the National Institute for Standards in Technology (NIST) AI Risk Management Framework, and takes cues from existing and future global regulation, such as the European Union’s AI Act.

Brookings scholars from across the institution weigh in on the ability of the EO to deliver on its promises, and areas that require further attention and exploration.

Nicol Turner Lee

The tireless efforts of researchers and civil society advocates have finally made it into the nation’s most aggressive proposal to advance equity, privacy, and national security in artificial intelligence (AI) systems. The White House receives a round of applause for advancing nondiscrimination in AI systems and imploring federal agencies to demonstrate such as part of their policies on procurement and general use. The consequential impacts of AI in use cases that include criminal justice, employment, education, health care, and voting have foreclosed on equal opportunities for historically disadvantaged groups and other vulnerable populations. Predictive socioeconomic determinations and eligibility screening done by AI can result in denials in credit, rejection from health care programs, and even assessing higher bail and sentencing on certain defendants when used in criminal justice settings.

While the EO specifically calls out these and other points in the design and deployment of AI, more clarity is needed. That is, how is a civil rights violation identified in opaque AI systems, and who decides if the situation presents itself as worthy of punitive action? Additionally, what will be the recourse for individuals harmed by discriminatory AI systems? On these points, Congress will definitely have to provide guidance to federal agencies. Who is seated at the table in the design and deployment of AI also matters, especially the inclusion of academic, or civil society experts that understand the lived experiences of communities (including their trauma) who have become the primary subjects of existing and emerging technologies.

The U.S. Department of Justice and other federal agencies have an obligation to extend their authority into this space as per the EO. Yet, it is still unclear how and when this will happen—all while critical systems wreak havoc on the participation of vulnerable populations and their communities.

Joseph Keller

The recent Executive Order by the Biden-Harris Administration advocating for safe and secure AI deployment is a welcome development, including its goal of advancing American AI leadership abroad. Congressional action is still essential, yet a significant competitive advantage cannot be overlooked. While the U.S. seeks to keep pace with the regulatory progress of international contenders, it has an opportunity to secure a lead in sustainable AI development and improve transparency around AI’s global environmental impact.

AI technologies impact our natural resources and climate, however, available environmental information about their effect is poor. Large-scale algorithms, including language models, consume substantial energy and natural resources during training cycles, often powered by non-renewables. Despite AI companies’ purported sustainability initiatives and carbon neutrality claims, crucial environmental data are not always collected or disclosed. A fundamental area for improvement is increasing transparency for AI emissions and resource usage.

As U.S. companies make voluntary commitments to the White House related to AI safety, security, and trust, the tech industry must also pledge to improve their transparency around the environmental impact of AI. Leadership abroad must begin with leadership at home; the U.S. is currently at a disadvantage. The EU and U.K. have already begun to enhance reporting by tech companies on carbon emissions and water usage, acknowledging the interaction between AI development, the environment, and climate change. The U.S. could meet this emerging challenge by becoming a leader in mandating the reporting of meaningful environmental data and metrics from tech companies.

Cameron F. Kerry

Monday’s Executive Order on AI might be the longest and most detailed in history. It is definitely the most comprehensive and thorough in my experience. The EO amounts to full mobilization of the federal government around AI. Almost every federal department or agency has some significant role in carrying out one or more of the Order’s eight priorities for AI policy, with timelines of less than one year to develop guidelines, propose regulations, or compile reports that will shape the AI landscape and apply the White House Blueprint for an AI Bill of Rights and National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) AI Risk Management Framework. These actions will carry over to federal contractors, research grantees, and sectors like critical infrastructure providers, health care, life sciences, employment, education, and the development of large foundational models and open-source models going forward.

All this will strain agencies’ capabilities to master AI. The EO recognizes this challenge in directing a “talent surge” in the next 40 days. That will be an early test for execution of the EO.

I focus on privacy and, in addition to AI safety (in anticipation of the U.K. AI Safety Summit this week), the EO has equity and privacy as running themes. The accompanying fact sheet reiterates the president’s support for privacy legislation but, in contrast to his State of the Union address, makes clear this is aimed at “comprehensive privacy legislation.” The section of the EO on privacy directs two potentially impactful initiatives. One long overdue is a review of federal government purchasing and use of “commercially available information,” i.e., the vast secondary market for personal information available from many sources. The second is guidelines on privacy-enhancing technologies for federal agencies as well as research in the field, for which White House Officials say there are resources.

The provisions on international cooperation resonate with our work on the Forum for Cooperation on AI (FCAI). In particular, the EO directs the Commerce Department to lead global engagement with international partners and standards development organizations on promoting and developing consensus standards. The vital importance of AI standards as a bridge for interoperability among differing regulatory systems has been a recurring finding of FCAI discussions among an international cross-section of government officials and experts.

Aaron Klein

Sometimes what is not mentioned is telling, and this Executive Order largely ignores the Treasury Department and financial regulators. The banking and financial market regulators are not mentioned once, while Treasury is only tasked with writing one report on best practices among financial institutions in mitigating AI cybersecurity risks and provided a hardly exclusive seat along with at least 27 other agencies on the White House AI Council. The Consumer Financial Protection Bureau (CFPB) and Federal Housing Finance Agency heads are encouraged to use their authorities to help regulated entities use AI to comply with law, while the CFPB is being asked to issue guidance on AI usage that complies with federal law.

In a document as comprehensive as this EO, it is surprising that financial regulators are escaping further push by the White House to either incorporate AI or to guard against AI’s disrupting financial markets beyond cybercrime. Given the recent failures of bank regulators to spot obvious errors at banks like Silicon Valley, the administration’s push to incorporate AI for good could have found a home in enhancing bank regulators whose reputations are still suffering after the spring’s debacle.

AI is of particular interest in the allocation of consumer credit, where the dominant FICO model advertises its usage of AI while critics complain that FICO scoring perpetuates racial and other biases in credit and opportunity. I hope the White House AI Council and the CFPB prioritize creating a level playing field between new AI-based technologies and older AI like FICO. Failure to do so will result in continued denials of credit to credit-worthy people, and disproportionately people of color, if newer AI systems are held to standards that are difficult to achieve, while FICO remains grandfathered in and exempt from new rules.

Anton Korinek

The White House Executive Order is an important step in the right direction. Having called for “Frontier AI Regulation” in a coalition paper earlier this year, I am encouraged that the administration is taking the safety risks from frontier AI systems so seriously. Although much remains to be done, this EO means that I will sleep a little better tonight.

As an economist, I also appreciate the initiative to support workers. However, I would recommend taking additional steps to prepare for more fundamental disruptions of the workforce. At the moment, nobody knows how fast AI will continue to advance, but we need to think very seriously about the possibility that it may acquire the capability to perform virtually all white-collar work relatively soon.

Mark MacCarthy

President Biden’s sweeping AI Executive Order properly avoids setting up an agency with a mission to regulate AI. Researchers have known for years that the benefits and risks of advanced AI make themselves felt only as the AI models are used in particular applications.

Instead, the EO urges the specialized agencies to address the AI risks within their area of expertise. The Federal Trade Commission is tasked with promoting competition in the development of AI systems. The Department of Health and Human Services is mandated to develop a system of pre-market assessment and post-market oversight of AI-enabled health care technology. But the EO does not push the legal envelope to give these agencies new powers to regulate AI outside the national security area.

In contrast, the EO uses the Defense Production Act to require AI companies to report to the government the results of safety tests and other information when they train AI systems that might have national security or critical infrastructure risks. An administration official warned that they were prepared to go to court through the Department of Justice to enforce these mandates if necessary.

But, beyond this, it is pretty slim pickings when it comes to new requirements compelling AI companies to act in the public interest.

Agency after agency is told to develop voluntary standards, principles, and best practices, as if these optional measures are all that is needed. The Department of Commerce, for instance, is required to develop standards for watermarking AI output. But these watermarking standards will apply only to government agencies. The private sector is free to adopt these standards or not as it sees fit.

Legislation will be needed to strengthen the capabilities of existing agencies outside the national security area to meet the challenges of AI. Other than a new privacy law that would protect kids, the EO does not identify where the administration needs new authority to regulate AI effectively. This is a missed opportunity.

(As the administration thinks through its legislative recommendations going forward, it might consider the idea proposal put forward by Alex Engler, a former Brookings scholar now with the Office of Science and Technology Policy, outlining what new powers for existing agencies would help them meet the challenges of regulating AI.)

Mark Muro

Ultimately, the management of AI needs to be comprehensive and global. As a general-purpose technology with sprawling potential impacts, its reach will soon be ubiquitous. For that reason, it is critical that President’s Biden’s sweeping EO on AI tackles a broad array of issues and comes as other governments around the world advance their own efforts to regulate advanced AI systems.

And yet, several important aspects of President Biden’s Order are highly grounded. Aimed at countering local gaps in access to AI’s build out and benefits, these “place-based” provisions in the EO break from the more abstract or conceptual elements of the framework to underscore that AI, too, will tend to benefit some people and places more than others, and that a sound management framework must speak to that.

Recent work from Brookings Metro has noted the emerging unevenness of AI research activities and the generative AI workforce. Therefore, it is welcome to see provisions in the EO aimed at catalyzing AI research across the U.S. and promoting a fair, open, and well-distributed AI ecosystem in many regions. Also welcome are provisions focused on “supporting workers” by investing in “workforce training and development that is accessible to all.” To be sure, the EO could go farther in this vein. But even so, the document will likely lend momentum to several highly relevant place-oriented initiatives already gaining traction. For one, the EO namechecks the need to pilot and develop the National AI Research Resource. The resource proposes democratizing access to an array of essential data and computation resources, including across all places to better include AI researchers and students far from the usual Big Tech research hubs. Not specifically named but surely implicitly elevated, meanwhile, is the National Science Foundation’s National Artificial Intelligence Research Institutes program. Through the institutes, 19 widely distributed universities are pursuing diverse, locally relevant research agendas that serve nearly 40 participating states. These institutes stand out as a widely distributed network of place-based hubs for research, talent development, and commercialization.

To the extent that President Biden’s important EO reinforces the need for “place-based” efforts like these, it will help ensure that the nation brings to bear the full array of policy tools at its disposal. And it goes without saying that the nation will need every tool it has to wisely manage what the president this week called “the most consequential technology of our time.”

Chinasa T. Okolo

The Executive Order on Safe, Secure, and Trustworthy Artificial Intelligence is a promising step toward the enactment of formal AI legislation within the United States. Throughout the Order, there is mention of consulting academic, civil society, and private sector stakeholders. However, there needs to be more understanding of how the government aims to engage the general public in these conversations. While civil society organizations have commonly filled the gap in public engagement in science and technology, the Biden-Harris administration and future administrations should try to include more stakeholders, who are most at risk of being harmed by AI.

The EO heavily focuses on protecting Americans from the harms of AI systems, and rightly so. Actions, such as requiring safety test results from developers of high-risk models and developing methodologies to ensure the safety of AI systems, could set a strong precedent for AI development and integration. While the onus should be on companies to comply with AI regulations, more efforts are needed to ensure that the public is aware of the increasing role of AI in everyday scenarios that range from employment screenings to social assistance disbursements and medical decision-making.

Along with a general lack of AI literacy within the American population, low levels of data and privacy literacy are issues that could affect how citizens utilize and interact with AI systems. While the EO emphasizes the protection of Americans’ privacy through external means, such as through the development of privacy-enhancing technologies, these methods can only do so much if citizens are not aware of how to restrict the use of their personal data and how to prevent unintended sharing of confidential information. As the United States moves closer to regulating AI, educating the general public about the limitations, benefits, and harms of AI will elevate the role of everyday Americans in effective oversight and empower them to become active stakeholders.

Courtney Radsch

The White House Executive Order on AI is an effort by the Biden-Harris administration to turn principles into action through leading by example and leveraging its power to set priorities for the federal government. By mobilizing the alphabet soup of federal agencies to collect information and examine how AI is used and the risks it poses in their specific domains, the U.S. is teeing itself up to have a more impactful conversation at the U.K.’s AI Safety Summit. The EO provides the administration’s assessment of the most pressing safety and security issues, some in significant detail, while recognizing that there is still a lot to learn about these, so expect a flurry of reports, papers, and committees to emerge in the coming months. The EO covers a lot of ground but focuses primarily on shaping how government agencies, particularly the Department of Commerce and the Department of Homeland Security, and existing law can address particular AI challenges while signaling to the private sector how the current government plans to address existing challenges.

The administration’s EO emphasizes safety, equity, and consumer protection as essential to establishing trustworthy AI systems while stressing the need to promote innovation and competition, yet nowhere in the 20,000-word document does the term “public interest” appear. Left unsaid is the fact that many of the most pressing risks created by generative AI have been enabled by a handful of Big Tech firms that were allowed to collect vast amounts of data without permission or compensation, develop incredibly energy-intensive models and services that have significant environmental implications, and release products that even their own teams said were not safe for public release. The Federal Trade Commission (FTC) gets relatively short shrift given its central role in shaping market dynamics that are fundamental to address many of the most pressing threats and though it is specifically “encouraged” to use its rulemaking authority to ensure fair competition and safety for workers and consumers. The EO does not address the fact that Big Tech has been allowed to dramatically increase the quality and quantity of numerous competitive advantages, from data to computational power to access to chips and cloud services. Given the power that Big Tech already wields over our information and communication systems and the economy, this dynamic will need to be addressed if the administration is serious about mitigating generative AI risks and minimizing harm.

John Villasenor

The White House Executive Order will play an important role in growing an AI workforce. For example, it requires the National Science Foundation “establish at least four new National AI Research Institutes” and coordinate with the Department of Energy to enhance programs to train AI scientists. The Order also instructs the State Department and the Department of Homeland Security (DHS) to streamline visa applications “for noncitizens who seek to travel to the United States to work on, study, or conduct research in AI,” and instructs DHS “to clarify and modernize immigration pathways for experts in AI and other critical and emerging technologies.” In combination, these measures will play an important role in increasing the number of people in the U.S. workforce with AI expertise.

More concerningly, the EO contains a problematic expansion of the Defense Production Act. The DPA was originally enacted at the height of the Cold War to, as the bill’s longer title stated, “facilitate the production of goods and services necessary for the national security.” In recent decades, presidents have invoked the DPA for purposes well outside its original intent. The AI Executive Order unfortunately continues that trend, invoking the authority of the DPA to establish a comprehensive new regulatory framework on companies developing large AI models.

Citing the DPA, the Order instructs the Department of Commerce to require “companies developing or demonstrating an intent to develop potential dual-use foundation models to provide the Federal Government, on an ongoing basis, with information, reports, or records regarding . . . any ongoing or planned activities related to training, developing, or producing dual-use foundation models.”

Even more concerningly, the Order, also under the purported authority of the DPA, mandates the creation of what amounts to a target list for any geopolitical adversary that might want to engage in cyberespionage or launch a large-scale cyberattack on U.S. AI computing infrastructure: It instructs the Department of Commerce to require companies to report to the government “the ownership and possession of the model weights of any dual-use foundation models, and the physical and cybersecurity measures taken to protect those model weights.” And the Department of Commerce will require “Companies, individuals, or other organizations or entities that acquire, develop, or possess a potential large-scale computing cluster to report any such acquisition, development, or possession, including the existence and location of these clusters and the amount of total computing power available in each cluster.” Hopefully the government will keep the resulting database of collected information secure from the inevitable exfiltration attempts, though history is not particularly encouraging on that front.

Darrell M. West

I applaud the federal government for issuing a new AI Executive Order designed to protect consumers, promote innovation, and safeguard national security. It is long overdue given the broad-based deployment of algorithms and possible dangers to ordinary people. AI is being utilized in education, healthcare, e-commerce, transportation, and national defense, among other areas. Algorithms are involved in collegiate yield management, medical drug discovery, autonomous vehicles, and product recommendations.

Yet the EO doesn’t go far enough in the crucial area of disinformation. With recent advances in generative AI, I expect a tsunami of disinformation in the 2024 elections and this EO does little to stem the likely flood of fake videos, false narratives, and inaccurate material. As we have seen in the recent Israel-Hamas war, false narratives and fake videos have proliferated with ominous consequences for how people view the conflict. It is hard to distinguish real from fake information, and viewers are already being subjected to old videos repackaged as current ones and footage from other regions presented as coming from the Middle East.

I expect similar problems in the upcoming U.S. elections. There are many foreign and domestic entities that see 2024 as a high-stakes and closely fought campaign, and this creates considerable incentives to win at any cost. Several countries with sophisticated tech capabilities already have a preferred winner based on their views regarding foreign policy, and some of them very well could interfere with the American election.

The EO helpfully directs agencies to authenticate official content through watermarking. But, without additional legislation, it can’t address AI content coming from beyond the government or outside the United States. Protecting the country from foreign intervention should be an area of bipartisan agreement since no Republican or Democrat should want the 2024 election decided by false content from abroad. Congress needs to move expeditiously to enact disclosure requirements on AI-generated content in campaign communications and make sure AI systems are safe and trustworthy. The federal government has considerable power through its procurement process to develop standards and best practices and legislators should extend the dictates of the Order to non-governmental and foreign entities.

The multiple applications and threats of AI recall the Greeks’ multi-headed mythological monster, the Hydra. President Biden’s 111-page Executive Order on AI is an awe-inspiring attempt to take a swing at each of the AI Hydra’s heads. The speed with which the administration moved to develop this policy makes it even more notable.

The EO is “the strongest set of actions any government in the world has ever taken,” Bruce Reed, who will chair a new White House AI Council, explained. Perhaps even more important, it is a sharp break from the last several decades of the government’s laissez faire approach to the challenges of the digital era, such as social media.

But it isn’t enough.

The scope and scale of the needed AI oversight are so vast that they exceed the executive authorities available to the president. Moreover, the EO can be overturned with the stroke of a pen by the next president.

The most consequential aspect of the EO was deploying the Korea War-era Defense Production Act—which gives the president authority to mandate and enforce action—to require the developers of large-scale foundation models to notify the federal government while the model is being trained and share the results of safety tests. As Big AI pushes the boundaries, there still remains free open-source AI models available to be modified for good or bad by anyone with a “beefy laptop.”

The president called on federal agencies to create an AI officer to expand the use of AI in the governing process, and for standards in AI procurement and funding. He also repeated an earlier call for regulatory agencies to use their existing authorities to address AI-enhancement of illegal activities, such as fraud and discrimination. Beyond these actions, the president’s mandatory authority runs dry and the remainder of the EO confronts issues only Congress can address. In place of enforceable requirements, federal agencies are instructed to develop programs to offer “guidance” or establish “standards,” all of which are good and important but fall short of mandatory and enforceable requirements.

The president and his team should be saluted for their speedy push to move as far and as hard as possible within existing authority. The issues have been identified; the path has been charted—now it is time for the Congress to step up to provide the necessary tools for meaningful long-lasting oversight.

Andrew Wyckoff

President Biden’s Executive Order is a much-anticipated step towards implementing the voluntary agreement struck with U.S. tech leaders in July. When Brookings colleagues talk about whether it will deliver the needed protections, they generally speak about the U.S., but given the global nature of AI, international coordination will be needed to adequately deliver the needed protections. The good news is that on the same day the White House issued the Executive Order, the Japanese Presidency of the G7 issued a G7 Leaders Statement on the Hiroshima AI Process that includes its own “International Code of Conduct for Organizations Developing Advanced AI Systems” that mirror many elements of the EO.

While the White House and the State Department deserve credit for this choreography, so do the Japanese and the G7 as an institution. Few recall that thanks to the Japanese, the G7 has been collectively discussing AI policy since 2016 when Digital Ministers met for the first time and the Japanese tabled a proposal for eight “Guidelines for AI R&D,” including transparency, safety, and accountability. This launched the development of the OECD’s AI Principles that were adopted first by the OECD and then were copied by the G20 in 2019 under a Japanese G20 presidency. In all, 50 countries signed onto these principles that provide an early common international approach to AI governance.

The AI dialogue has continued at the G7 with each successive presidency since and has resulted in the creation of the Global Partnership on AI (GPAI) in 2020, led by Canada and France, and the Global Forum on Technology by the U.K. in 2021 that will look at other emerging technologies like quantum computing and synthetic biology.

Principles are important, but ensuring implementation and compliance is essential and must be the priority. While the G7, which includes the EU, is a good starting point, it is far from global. The U.S. needs to work with its partners to build on this base. A logical next step for the OECD’s 38 member countries and six accession countries would involve a collective review of OECD’s AI Principles in 2024, but this needs to be done in a coordinated fashion with the G20 under a Brazilian presidency and as part of the UN Global Compact, which can accelerate its work by building on these international agreements.

Rashawn Ray

The effectiveness of President Biden’s Executive Order on artificial intelligence must first rest on its ability to enforce a methodological standard among companies and organizations that could lead to the publication of results in academic journals. Many academic journals employ at least a .05 significance level—meaning that 95% of the time there is confidence that the results are valid. It is imperative for this threshold to be reached before artificial intelligence tools are deployed, particularly in settings that alter life outcomes such as policing, court rulings, health care decisions, and employment.

Second, equity and fairness must be major criteria in the deployment of artificial intelligence tools. The federal government must ensure that artificial intelligence tools operate similarly regardless of a person’s background. For example, facial recognition software has continuously misclassified people, particularly when breaking down the utility of the software by race and gender. One study found that Black women were misclassified every one out of three times, while another study found that a facial recognition program misclassified one out of every five elected officials as criminals. Some of these outcomes are predicated on the lack of diversity in the creation and testing of artificial intelligence tools. This needs to change. As a scholar who readily uses artificial intelligence and has helped to create various software, significance testing and equity must be centered if we are to really see the true promise of artificial intelligence to create a more equitable society rather than simply replicating our inequitable one.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).

Commentary

Will the White House AI Executive Order deliver on its promises?

Brookings experts weigh in

November 2, 2023