Part one of the “invisible primary” ended with the end of summer. On the Republican side the dominant theme was how high Donald Trump could go. On the Democratic side the dominant theme was whether or not Hillary’s problems were serious enough to induce someone else into the race. And so we saw some predictable bubbles; a short one for Secretary of State John Kerry, the party’s 2004 nominee, a slightly longer one for former Vice President Al Gore, the party’s 2000 nominee and winner of the popular vote, and an ongoing one for sitting Vice President Joe Biden, who has run for president unsuccessfully before but who now has new stature in the party.

As we head into the fall it’s fair to ask—is the Democratic field set? Or not? On the Republican side it probably is—with seventeen candidates in the race there aren’t many people who are not running for president. But in spite of all the talk about other candidates on the Democratic side that field is probably set as well. Putting aside the question of how serious Hillary’s problems are (I, for one, am not in the “bed-wetter” camp that is easily panicked) there are serious structural problems that will, very shortly, keep anyone who is not already in this race from getting in. Conventional wisdom says a candidate has to get in early in order to raise money. That’s true for unknowns but any of the nationally recognized candidates mentioned above could, thanks to the Internet, raise a fair amount of money pretty quickly. The more serious problem is that presidential nominees these days get elected in public primaries and public primaries have filing deadlines.

A candidate who is not on a primary ballot can’t win delegates from that state – pure and simple. And so missing a filing deadline is akin to forfeiting delegates to the convention. Candidates who have tried to convince delegates pledged to other candidates to switch to them (think Senator Ted Kennedy in 1980) have found it almost impossible to do. And in recent years almost no one votes for “uncommitted” on primary ballots, so there are hardly any free agents in modern conventions willing to be wooed by a late entrant with a great message. In some states the filing deadlines are pretty simple—sign a paper and write a check. In others a modicum of organization is required to collect sufficient signatures from voters. Whatever, the case however, meeting the deadlines requires an organization in place.

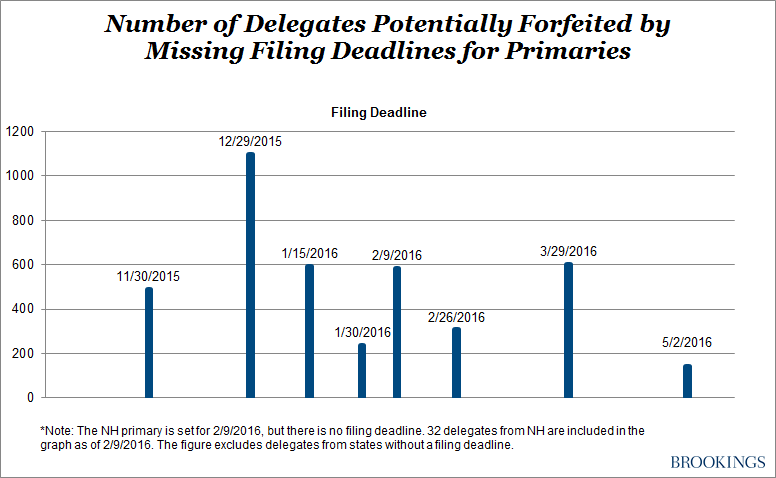

Graph #1 shows filing deadlines along the horizontal axis and number of delegates potentially forfeited along the vertical axis. (These charts are based on Democratic primaries but the story is basically the same for the Republican Party as well. The deadline for New Hampshire has not been set yet.) By the end of November a candidate who is not in the race and on ballots has forfeited around 500 votes. By the end of December, a candidate not on primary ballots has forfeited more than 1000 votes. And so on.

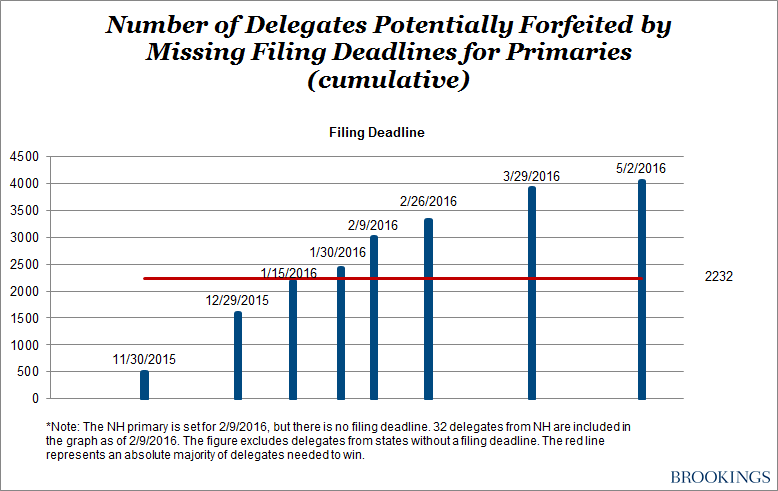

As the next graph indicates, the candidate who has missed filing deadlines through the end of January, has potentially forefeited 2232 delegates, the number needed to win the Democratic nomination! Since the all important early contests, of Iowa, New Hampshire and South Carolina tend to end up happening in January it will be very difficult for someone sitting in the wings and waiting for Hillary to crash and burn to get into the race at that point.

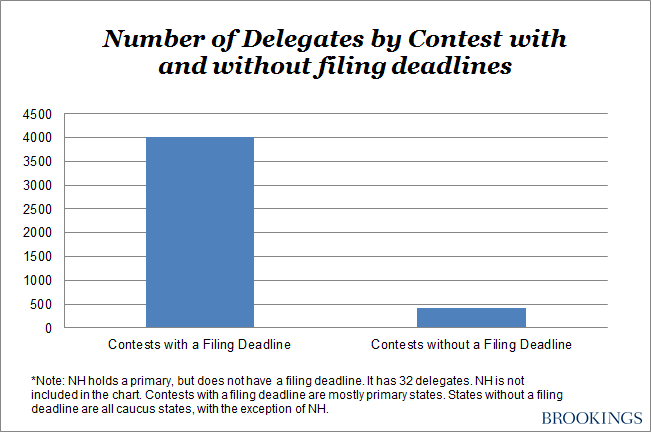

And, as the final graph illustrates, there are very few delegates apportioned to candidates in contests that do not have filing deadlines. All primaries and some caucus states have filing deadlines. The few states that have no filing deadlines are caucus states whose total number of delegates amounts to less than 500.

Unless Vice President Biden or someone else moves quickly to get into the Democratic race they will be blocked out. Late entrants can scramble to raise money and put together a staff, they can afford to miss debates; but no one can afford to miss filing deadlines.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).

Commentary

Will anyone else get into the Democratic race for president?

September 8, 2015