Politicians who complain about college costs frequently cite two numbers: one trillion and seven million. Student borrowers owe more than $1 trillion, and seven million borrowers are in default, according to the latest Department of Education data.

It’s natural for people listening to the politicians to connect the two facts with a causal arrow: More debt leads to more default. But the reality is surprising: Borrowers who owe the most are least likely to default.

The reason for this strange pattern? The biggest borrowers tend to become the highest earners.

In particular, borrowing is highest for those who go to graduate school. Forty percent of new loans go to graduate students. Among those earning law and medical degrees in 2012, median debt (undergraduate and graduate school) is $141,000 for lawyers and $162,000 for doctors.

Those holding graduate degrees tend to handle higher debt because they earn more. Over the past 50 years, workers with graduate degrees have enjoyed the largest gains of any education group, with their inflation-adjusted earnings nearly doubling since 1964. Some struggle, of course: The Department of Education estimates that 7 percent of graduate borrowers default. But this default rate is far lower than the 22 percent rate for those who borrow only for their undergraduate studies.

This fact about loan defaults is one way in which the national conversation about student debt is at odds with the data. In many people’s minds, the so-called student-debt crisis revolves around graduates of selective colleges or graduate programs who run up six figures in debt.

But such borrowers aren’t the real source of trouble. The vast majority of bachelor’s degree recipients do very well. Only 2 percent of undergraduates borrow more than $50,000, and they also aren’t the ones who tend to have problems with their debt.

The unemployment rate for four-year college graduates is currently 2.6 percent, and the typical household headed by a college graduate earns $58,000 more per year more than the typical household headed by a high school graduate.

Defaults are concentrated among the millions of students who drop out without a degree, and they tend to have smaller debts. That is where the serious problem with student debt is. Students who attended a two- or four-year college without earning a degree are struggling to find well-paying work to pay off the debt they accumulated.

We can see this in the Direct Loan program, the source of all federal loans for college students since 2010. The 3.2 million borrowers in default on these loans owe an average of $15,000, while the other 29.4 million borrowers owe an average of $26,000.

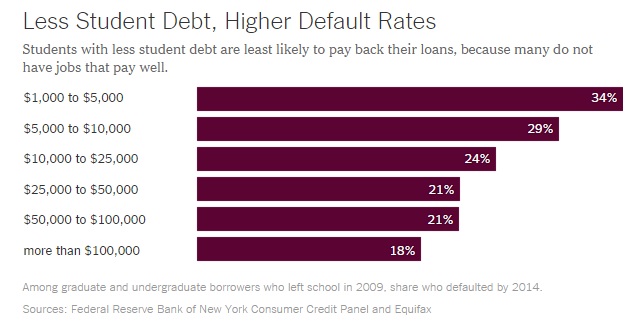

Most borrowers have small debts, according to the Federal Reserve Bank of New York; 43 percent borrowed less than $10,000, and 72 percent less than $25,000. And borrowers with the smallest debts are most likely to default. Of those borrowing under $5,000 for college, 34 percent end up in default. The default rate steadily drops as borrowing increases. Among the small group (just 3 percent) of those borrowing more than $100,000, the default rate is just 18 percent.

What does this all mean for loan policy? Getting students to borrow less is not an obvious path to reducing default, since 51 percent of defaulters left college with less than $10,000 in student loans.

The approach of some countries, including England and Australia, is to link payments directly to income so that borrowers pay little to nothing during hard times. The United States also has income-based repayment options, but relatively few student borrowers — currently 19 percent of Direct Loan borrowers — are enrolled in them. The people who need these programs the most are not taking them up.

Part of the reason is the complexity of the process. Getting into and staying in an income-based plan requires an annual round of complicated financial paperwork. As is true with the process of applying for student aid, those who most need a helping hand are probably least able to navigate this bureaucracy.

There are several proposals circulating around Washington by think tanks and policy advocates that would get more troubled borrowers into an income-based repayment plan. A coalition of student-aid organizations recommends making income-based payment the universal default option, as it is in England and Australia.

I have co-written a similar proposal, which also recommends extending the repayment period to 25 years, as is it in many countries. This allows for smaller monthly payments than the 10-year payment plan that is standard in the United States. The Institute for College Access and Success recommends keeping the standard 10-year repayment plan, but automatically shifting borrowers into an income-based plan if they fall behind on payments.

Of course, if no students borrowed, there would be no defaults. But student borrowing is not going to end. Even if tuition were eliminated at public colleges, as proposed by the presidential candidate Bernie Sanders, many students will still borrow to fund their living expenses. And none of the free-college proposals apply to private college, attended by 20 percent of students. Fixing repayment requires its own solution, distinct from efforts to reduce the price of attending a public college.

This post originally appeared in

The New York Times: Upshot

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).

Commentary

Op-edWhy students with smallest debts have the larger problem

August 31, 2015