Public transportation advocates as well as proponents of dense, walkable cities have long drawn a connection between population density and the efficacy of public transit. But if population density is a good measure of a metro area’s car (in)dependence, why is Los Angeles—which has the nation’s second-highest population per square mile of developed land—a byword for car-dependent sprawl that writer Dorothy Parker once called “72 suburbs in search of a city”?

The short answer is that typical measures of population density don’t capture the sort of urban concentration that encourages walking and public transportation use. For non-automobile travel to be a viable option, many types of trip destinations—not just to residences—need to be easily accessible. As discussed in a new Brookings report, the concentration and mixture of a variety of urban uses in clusters we call “activity centers” is more important than population density in determining whether a metro area’s residents are more likely to use greener alternatives instead of driving alone to work.

Typical measures of population density aren’t useful predictors of green commutes

It’s true that metro areas where a relatively low fraction of the population drives to work alone tend to have high population densities. But the reverse is not: High population density alone is not enough to reduce solo-drive commutes.

Take Los Angeles. While it is not the most car-dependent large metro area (20.3% of commuters there did not drive to work alone in 2019, compared to the median of 15.5% across the 110 U.S. metro areas with at least half a million residents), it is hardly the most friendly to transit, walking, and biking. In 2019, the Los Angeles metro area ranked 14th among those 110 large metro areas in the share of commuters who use transit, with half or less than the share of any of the top seven metro areas. And despite operating the nation’s second-longest light-rail system and the ninth-highest hours of bus service per capita, Los Angeles ranked 10th in annual transit trips per capita according to 2019 Department of Transportation data.

Los Angeles is not unusual in having high overall population density while still being auto-dependent. Indeed, only half of the 10 densest large U.S. metro areas (ranked by population per square mile) are also among the top 10 for “green commutes” (the share of commuters who do not drive alone to work).

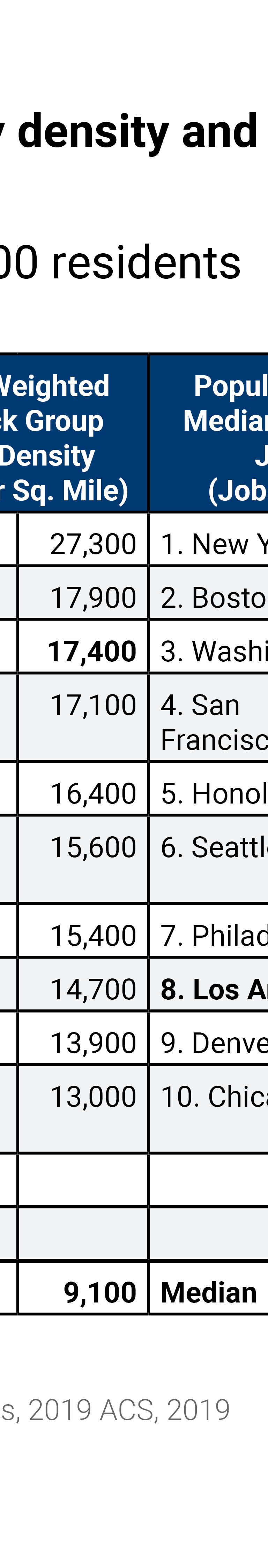

Part of the issue is that population per square mile doesn’t really capture the sort of density that makes walking, biking, and public transportation effective ways to get around. “Population-weighted” population density—the density at which half the residents of a metro area live at or above—provides a better picture of how dense the places most people live actually are. But even that is not enough to resolve the disparity between density and alternative modes of transportation; of the top 10 large metro areas by population-weighted population density, only five (New York, Honolulu, San Francisco, Washington, D.C., and Philadelphia) are in the top 10 for green commutes. The other five (Los Angeles, San Jose, Calif., Miami, Baltimore, and Las Vegas) have substantially lower green commute shares than cities such as Boston, Seattle, and Chicago, which are not on the list of cities with the highest population-weighted population densities.

Dense clusters of activity promote green commutes

Clearly, population density alone is not necessarily a driver of transit ridership. This makes sense if one considers that public transit is most efficient not only when there are many potential riders, but when there are many potential riders who want to travel to the same destinations. High concentrations of potential destinations attract more riders while also discouraging driving by increasing traffic congestion and competition for limited parking—making transit a more time-efficient and often less costly option.

In a new report, Mapping America’s activity centers: The building blocks of prosperous, equitable, and sustainable regions, I and my Brookings colleagues use a novel approach to identify and analyze these destinations. We call them “activity centers”—hyperlocal clusters of a mix of assets, including community institutions, tourism destinations, consumption amenities, major institutions, and jobs in traded sectors. Analyzing these clusters reveals a robust relationship between activity center density and transportation choice.

Look again at Los Angeles. As shown in the third column of the above table, the metro area ranks eighth when measured by its job density inside activity centers—a rank that, relative to the other density measures, more closely comports with its 14th-place rank on green commutes (as seen in the table’s fourth column). Los Angeles’ activity centers are both low in density and broadly distributed across the landscape; so, while a large share of residents live near at least one activity center, those centers simply cannot support a high rate of greener transportation options such as public transit, walking, and cycling. Residents thus have little choice but to drive to access jobs and services, particularly when they are not available in the activity centers closest to them.

The inverse of this relationship is also evident in the table: Eight of the 10 metro areas with the highest shares of green commutes are also in the list of top 10 metro areas by activity center job density. The two outliers are Portland, Ore., which barely misses the top 10 by activity center job density (it ranks 12th), and Bridgeport, Conn., where the large green commute share is primarily due to residents taking commuter rail to jobs in Manhattan.

Promoting public transit and other green commute options is only one benefit of strong activity centers. Our report also shows that metro areas with denser activity centers have higher overall productivity per worker, and that low-income and racial minority groups tend to live in areas with higher-than-average accessibility to activity centers. Together, these findings demonstrate that importance of activity centers to regions’ economic, social, and environmental health—and thus why they deserve public, private, and civic investment in their growth and revitalization.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).

Commentary

Why ‘activity centers’ are key to greener commutes

November 29, 2022