In normal times, and with some distance from the worst of COVID-19, we would take a moment to reflect on the long-term future of social protection. After all, World Bank research shows that nearly 1.4 billion people were reached by social protection measures across the globe during the COVID crisis, with an additional 300 million covered by recent inflation responses.

But these are not ordinary times. With the future clouded with uncertainty, getting clarity on six key issues is more urgent than ever.

1. Where has all the coverage gone?

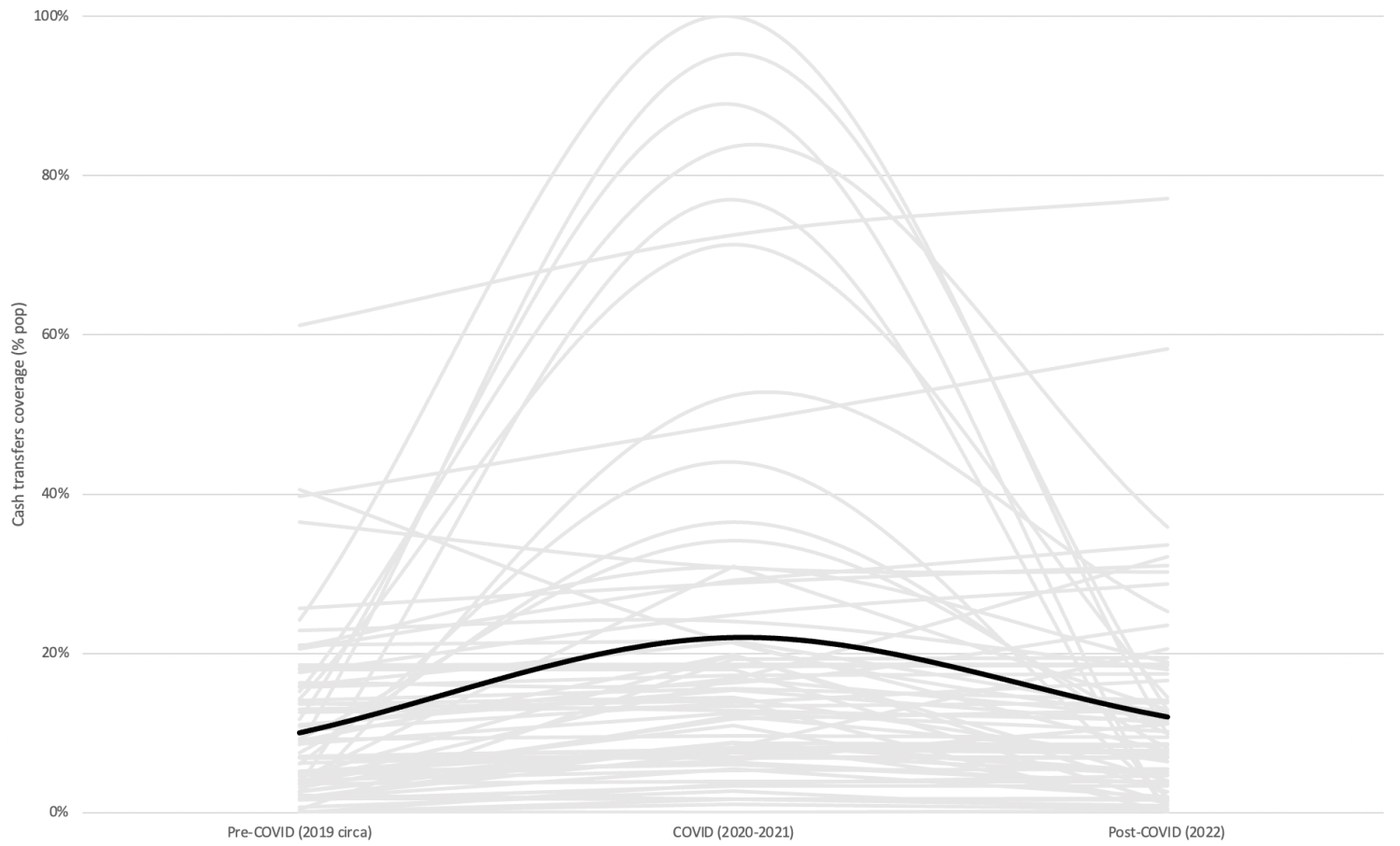

Since the historic COVID-19 social protection response, coverage seems “back to normal.” The fact that countries have been knee-deep in short-term inflation responses has contributed to a slight bump in coverage compared to pre-pandemic levels. Based on a sample of 71 cash transfer programs with available data for “pre-COVID” (circa 2019), “COVID” (2020-21) and “post-COVID” (2022), our estimates indicate that coverage of such programs followed an inverse-U shape: doubling in coverage during the pandemic, from about 10% to 22% of the population, before declining to around 12% in 2022 (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Cash transfer coverage is largely back to normal

Note: Coverage refers to highest coverage program in each country (n=71); programs include unconditional cash transfers, conditional cash transfers, social pensions, and public works; population data refers to 2021.

Source: Gentilini et al (2023, 2022); ASPIRE; staff estimates

Looking beyond averages, there is significant variation in country trajectories. Some countries like Brazil displayed a vibrant and evolving approach involving seven combinations of flagship and ad hoc cash interventions. In others, COVID-19 shifted the equilibrium of routine systems, albeit temporarily: in South Africa, the pandemic SRD/R350 cash program for vulnerable workers reached 12% of the population and will keep being active until March 2024—almost four years after its introduction.

2. From where and how will future coverage be attained?

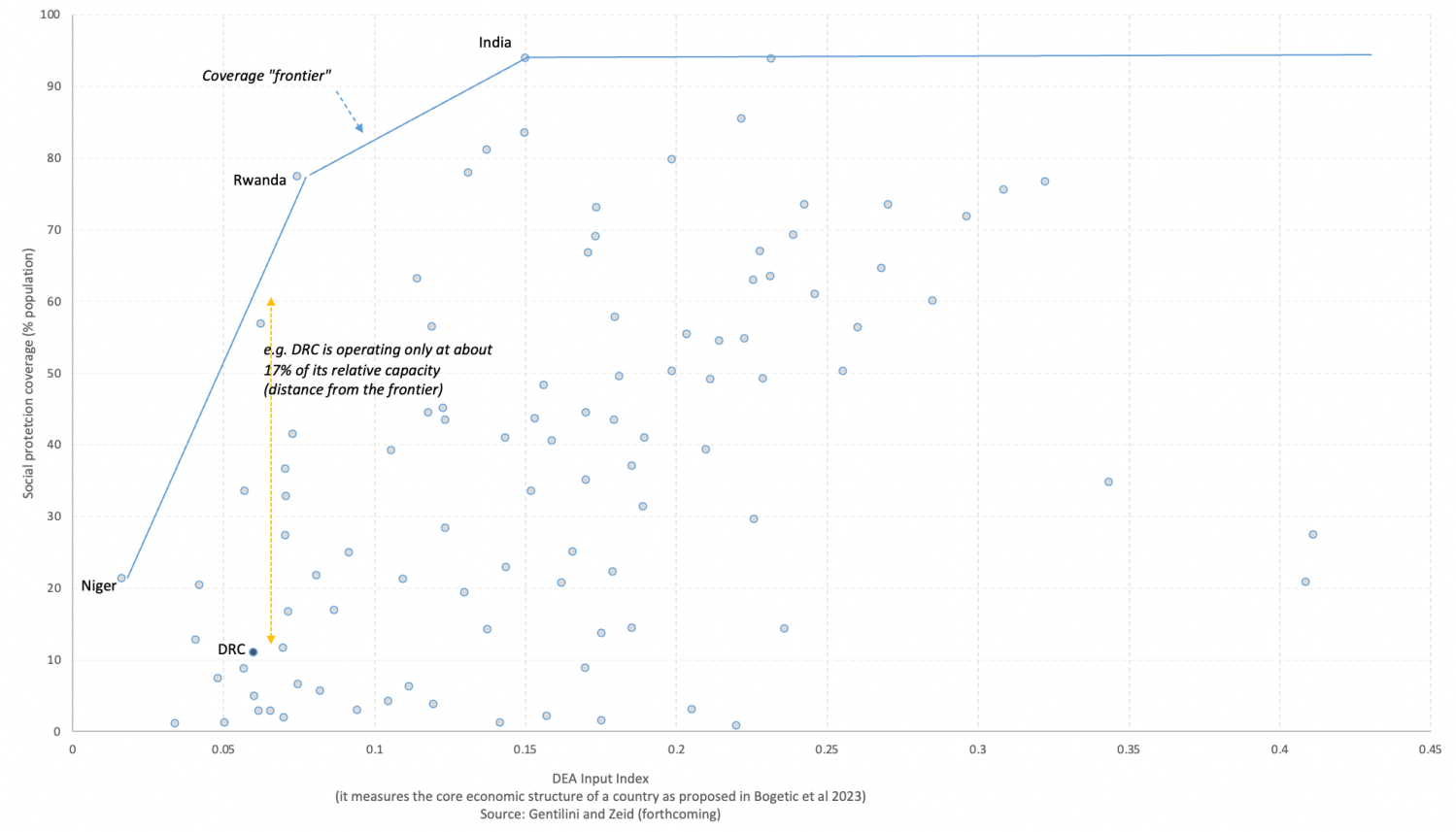

There is considerable momentum around the idea of scaling up social protection. But by how much? If universality is the absolute yardstick, then current global coverage of 57% of the population points to a gap of over 40 percentage points. (In an earlier blog, I estimated it would take between 65 and 240 years to achieve universality). There may be scope for scale up even within current capabilities: when benchmarked against the coverage “frontier” reached by their peers, countries are utilizing just 43% of their coverage potential on average.

Figure 2. There is untapped potential to expand coverage

Whether toward universality or relative to others, what instruments should be deployed to fill the coverage gap? Some of the largest-scale programs, like in-kind transfers, contributory pensions, and subsidies are subject to extensive debate (often to contain rather than expand coverage). Average population coverage of cash transfers is about 13%, but the appetite for wider scale is variable due to technical and mindsets-related issues. Interestingly, there is a family of insurance programs other than pensions—for unemployment, life, accidents, work injuries, health—that appears underutilized. Historically, short-term transfers have sometimes preceded the introduction of long-term insurance for age risks in high-income countries. These insurances may build on existing delivery platforms and bundle programs to help expand coverage.

3. Are we prioritizing social protection?

Spending reflects priorities, and with a slight repurposing of resources, social protection could be expanded considerably. In regions such as in the Middle East and North Africa, expenditures on energy subsidies are twice those on social assistance and over five times higher than spending on cash transfers. And globally, less than 3% of the roughly $200 billion in Official Development Assistance (ODAs) to low- and middle-income countries is devoted to social protection. In fragile contexts, less than 1% of the nearly $50 billion in humanitarian assistance is channeled through local governments, the institutional sites of social protection.

4. Is social protection enough?

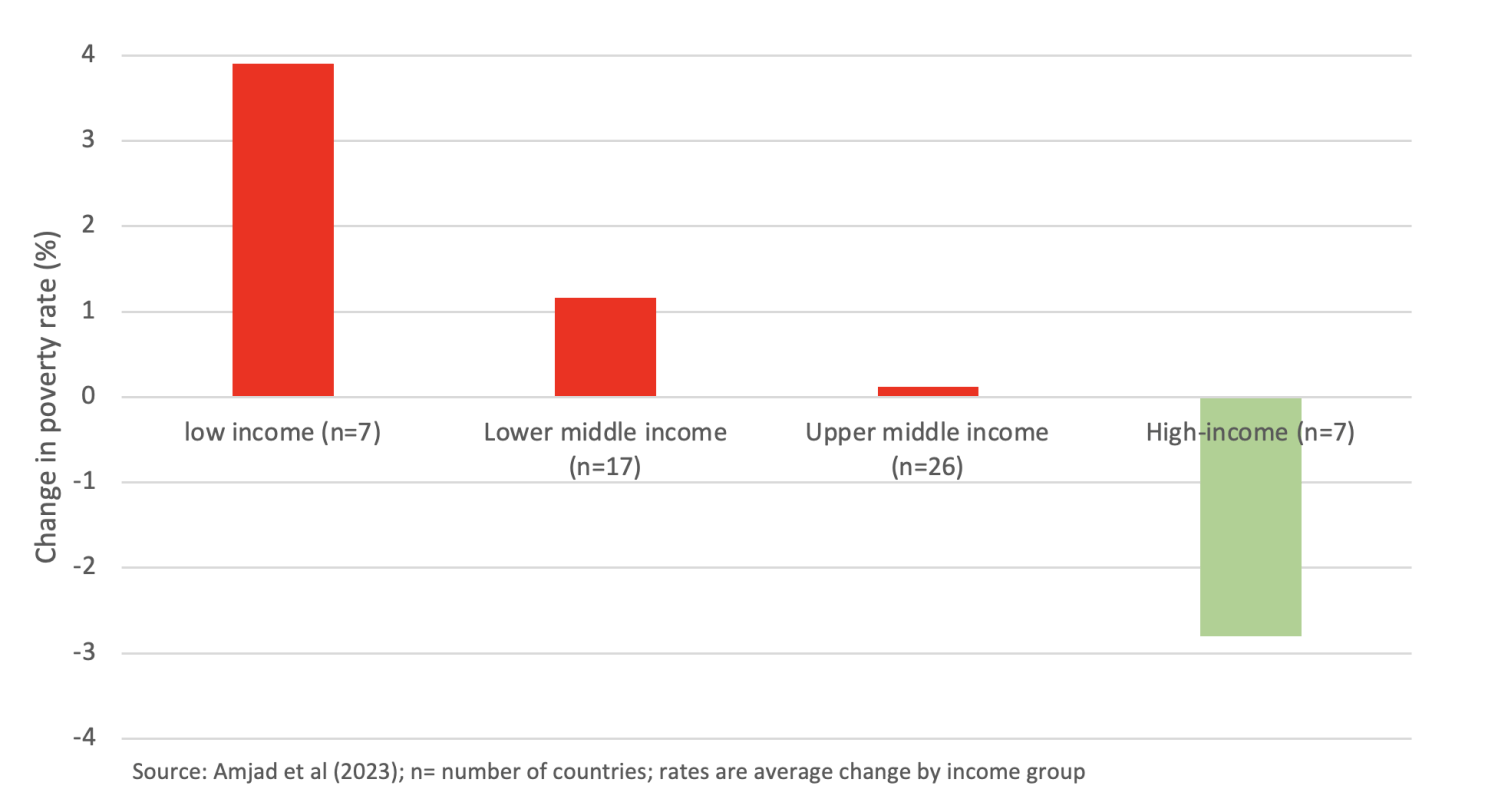

What’s the net welfare effect of a country’s fiscal policy when accounting for the complete set of direct and indirect transfers and taxes? Analysis from 57 countries across the income spectrum indicates that in 60% of the cases (including all low-income and most middle-income countries) fiscal policy can be poverty-augmenting (red bars in figure 3). This means that in the majority of cases, social protection and other human development investments are not overcoming the negative effects of fiscal policy. The ultimate effectiveness of social protection programs may hinge on attacking structural imbalances in fiscal fundamentals. This has important implications for how we communicate about social protection, how we set expectations, and how we manage “blame” when possible needs are unaddressed.

Figure 3. Fiscal policy often increases poverty ($5.5/day)

5. Should we redefine sustainability?

5. Should we redefine sustainability?

Think sustainability, and you think costs. Fiscal prudence is and will remain a linchpin of utmost importance. However, perspectives solely based on expenditures may provide an incomplete view of the dynamics at play: a systematic review of the evidence from over two dozen studies suggests that programs like cash transfers generate an average local multiplier of $1.3 (and up to $2.6) for every dollar injected through those programs. When multipliers are considered in tandem with investments in domestic revenue mobilization, the affordability of social protection programs could be interpreted in a more favorable light than when based on costs considerations alone.

6. In managing large crises, are we better prepared today than we were in 2020?

Some of the practical measures hastily implemented during the pandemic have been absorbed into routine delivery systems. It is unclear, however, if countries have reflected on the pandemic experience systematically — what lessons to draw, what to incorporate, and what not. Early signs point to modest changes: There are very few examples of making social protection more anticipatory, that is, being prepared for the next crisis. This includes establishing early warning systems, devising scale-up protocols and establishing a risk financing architecture. Sierra Leone is one of the few countries that took steps in such direction. If the COVID response was reactive, idiosyncratic, and blunt, the next generation of responses would need to be more anticipatory, planned, and customized. While the signals may be sobering, it is not too late to trigger this shift.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).

Commentary

Where has all the social protection gone … and where will it come from?

November 14, 2023