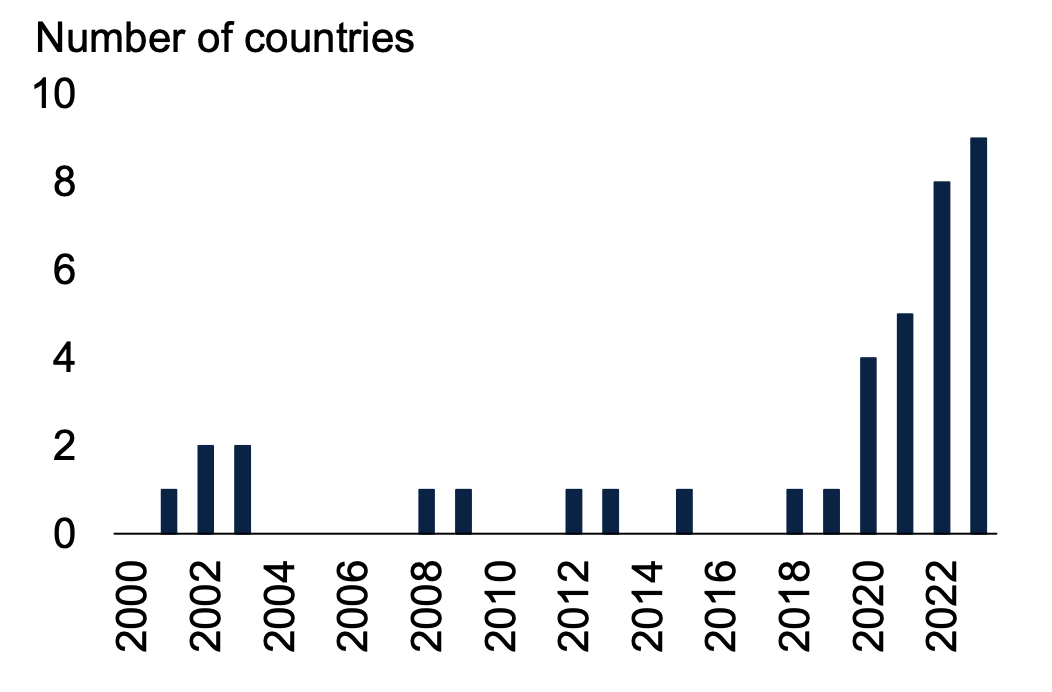

The number of emerging markets and developing economies in debt distress is currently the largest since 2000. With global growth slowing and interest rates remaining high, the next few months may bring more countries to the brink of sovereign debt distress. If past experience is a guide, more than one-third of these countries may fail to durably reduce their debt or borrowing cost—especially those that are unable to accelerate growth, improve fiscal positions, or obtain debt restructuring. Some countries may resort to replacing foreign borrowing with domestic borrowing. While this reduces their default risk, it has historically also been associated with higher borrowing cost and crowding out of the private sector. In short, in choosing between dealing with debt default and borrowing domestically to avert it, countries are caught between a rock and a hard place.

The largest number of emerging market and developing economies (EMDEs) since 2000 is now rated by Moody’s ratings agency as either in outright debt default or on the verge of it (Figure 1). Current global economic and financial conditions are such that more countries may well tip into debt distress over the next few months. Any sovereign defaults in the period ahead will incur considerable economic and social costs—and may not even succeed in lowering debt-related risks. In our recent study, we identify the most common factors associated with a durable improvement in fiscal positions after default and also the cost associated with one widely used strategy for averting default, domestic borrowing.

Figure 1. Number of countries in sovereign debt distress

Source: Moody’s rating agency; World Bank.

Note: Countries rated by Moody’s as C (obligations that are the lowest rated and typically in default, with little prospect for recovery of principal or interest) or Ca (obligations that are highly speculative and are likely in, or very near, default, with some prospect of recovery of principal or interest). Number of countries that were at some point during the year rated C or Ca. Unbalanced sample of 61-108 EMDEs since 2000.

Dealing with default

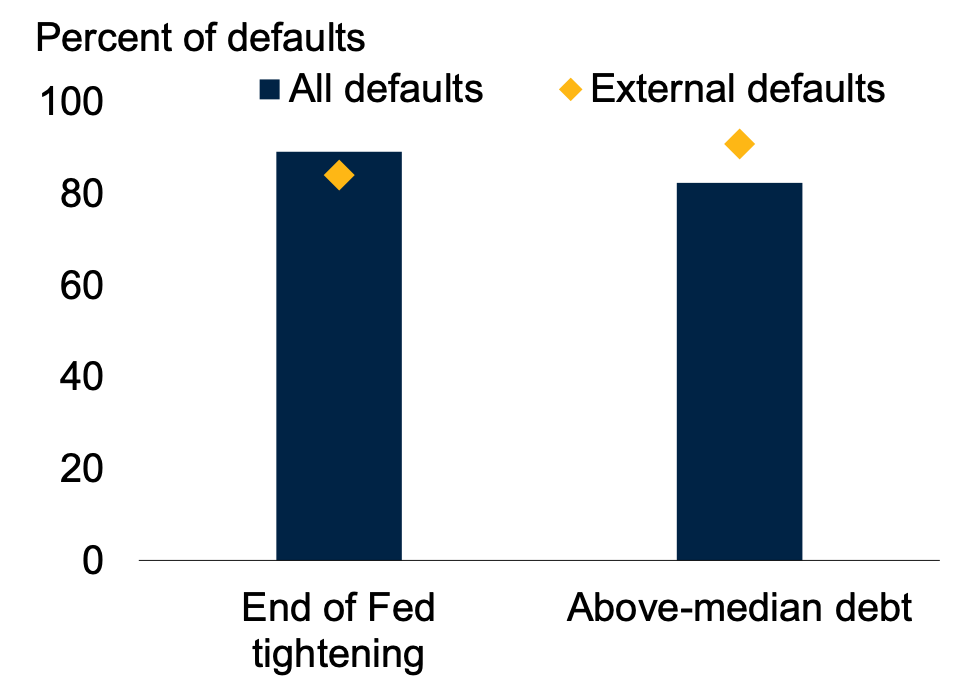

Since 1979, more than four-fifths of defaults in emerging market and developing economies (EMDEs) have taken place within a year of the end of a U.S. monetary policy tightening cycle and in countries with above-median government debt-to-GDP ratios (Figure 2). This was true for debt defaults on external creditors as well as for all debt defaults regardless of the creditor.

Figure 2. Share of sovereign debt defaults in the most common circumstances

Source: Asonuma and Trebesch (2016); Erce, Mallucci, and Picarelli (2022); International Monetary Fund; World Bank.

Note: Share of all defaults that occurred in the year of the end of U.S. Federal Reserve tightening cycle as defined in World Bank (2023) or in the subsequent year. Share of all defaults that occurred in country-year pairs with above-median (across the full EMDE sample) government debt at the time of default. All defaults include defaults on domestic and external creditors, external defaults refer to defaults on external creditors.

Many of these defaults failed to achieve lasting improvements in debt positions. Historically, more than one-third of sovereign debt defaults failed to lower the government debt-to-GDP ratio or the effective interest rate on government debt five years later. Among these “failed” defaults, the probability of relapsing into another default within five years was twice as high as among more successful defaults.

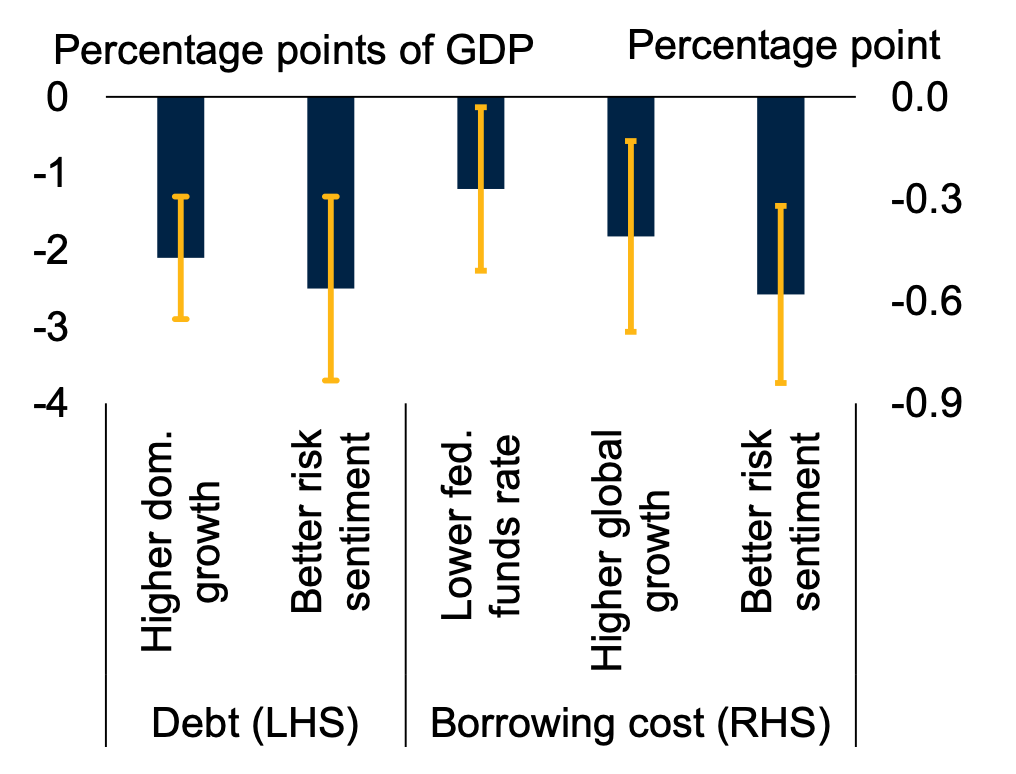

Debt defaults more often succeeded in durably reducing government debt ratios or government borrowing cost when growth was stronger and when global financing conditions were more favorable. This is what selection bias-corrected panel regressions suggest, based on up to 59 defaults in 37 EMDEs (among a sample of 145 EMDEs) during 1982-2018. The regression estimates indicate that the decline in government debt in the five years after debt default was about 2 percentage points of GDP steeper when domestic output growth was 1 percentage point faster. And the decline in effective interest rates on government debt was steeper when global conditions were more benign: When global growth was faster, global interest rates were lower, and global investor sentiment was better (Figure 3).

Figure 3. Predicted changes in government debt ratio and effective government borrowing cost five years after sovereign debt default

Source: World Bank (2023).

Note: Predicted change in government debt ratio or government borrowing cost is defined as 1 percentage point increase in domestic or global growth, 1 percentage point decrease in the U.S. federal funds rate, or half a standard deviation improvement in global risk sentiment during the sample period, multiplied by the coefficient estimate from a panel regression estimation, controlling for selection bias, as described in annex SL.1 of World Bank (2023). Government borrowing cost are defined as net interest spending divided by lagged gross government debt. Yellow whiskers indicate 95% confidence intervals.

Among external debt defaults, specifically, larger debt restructuring was also associated with more lasting government debt or borrowing cost reductions. Two-thirds of external debt defaults with an above-median share of restructured debt in total government debt, and nearly nine-tenths of external debt defaults with above-median haircuts, were associated with lower government debt five years after default (compared with one-half of other defaults).

Averting debt default

Some governments have resorted to domestic borrowing to reduce default risks. In the average EMDE, domestic debt accounted for 58% of government debt in 2022 and it has accounted for almost two-thirds of the government debt buildup since 2010.

Indeed, based on an event study of past government debt booms, domestically financed government debt buildups have been associated with a smaller probability of default than externally financed government debt buildups. Government debt booms can be defined as debt accumulations that raise the government debt-to-GDP ratio more than one standard deviation above its trend, in at least one year. By this definition, there have been 53 domestic government debt booms and 34 external government debt booms in EMDEs since 2004.

Only 2% of these domestic government debt booms ended in default—one-third the share among external government debt booms. This may have reflected the domestic currency-denominated nature of most domestic debt (so that it is less vulnerable to exchange rate shocks) and the fact that domestic investors tend to be less prone to loss of market confidence.

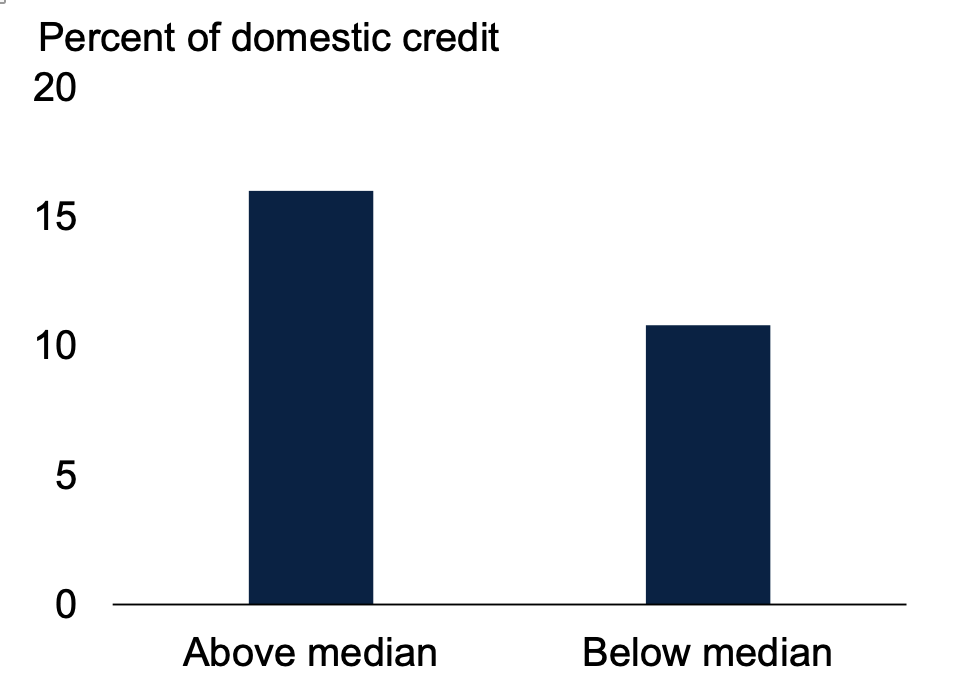

However, this reduction in default risk comes at a price. Between 2010 and 2022, above-average shares of domestic government debt in EMDEs have been associated with higher effective interest rates on government debt, shorter government debt maturities, and a smaller share of bank credit allocated to the private sector. For example, banks allocated 6 percentage points of domestic credit more to government—and less to the private sector—in EMDE with above-median domestic shares of government debt (Figure 4).

Figure 4. Financial system claims on general government, by domestic share of government debt

Source: IMF (various staff reports); IMF International Financial Statistics; Kose et al. (2022); World Bank.

Note: 2021 or latest available data for EMDEs with above-median or below-median share of domestic debt of government debt.

Balancing between a rock and a hard place

The external environment is likely to remain challenging. Global growth over the remainder of the 2020s is projected at 2.2% a year, down from 2.6% a year in the 2010s. Meanwhile, global financing conditions are expected to remain tight as advanced-economy central banks maintain elevated policy rates to rein in inflation, with bouts of financial stress likely to recur. It is therefore up to national governments to put in place the policies that reduce the probability of default and increase the chances of successful defaults when they occur.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).

Commentary

Between a rock and a hard place: Averting, or dealing with, sovereign debt default

October 31, 2023