The Vitals

Candidates and elected officials have many proposals to change how Americans get health insurance coverage, ranging from President Trump’s proposals to repeal and replace the Affordable Care Act (ACA) to proposals by some Democratic presidential candidates to create a single payer system. These proposals vary widely, sometimes because different policymakers have different objectives and sometimes because they disagree about how to achieve shared objectives. This piece provides an overview of how Americans get coverage today and how prominent proposals would change those arrangements.

-

The share of Americans without health insurance has fallen by more than two-fifths since enactment of the Affordable Care Act in 2010. Nonetheless, 30 million people are still uninsured and people with health insurance can struggle to afford care.

-

Some candidates and officials, notably President Trump, support plans that would reduce the generosity of federal coverage programs and reduce federal spending, but also the number of people with insurance.

-

Some candidates and officials, generally Democrats, support plans that would cover more of the uninsured by expanding federal health care programs and increasing federal spending. These proposals vary widely in scope.

A Closer Look

How do Americans get health insurance today?

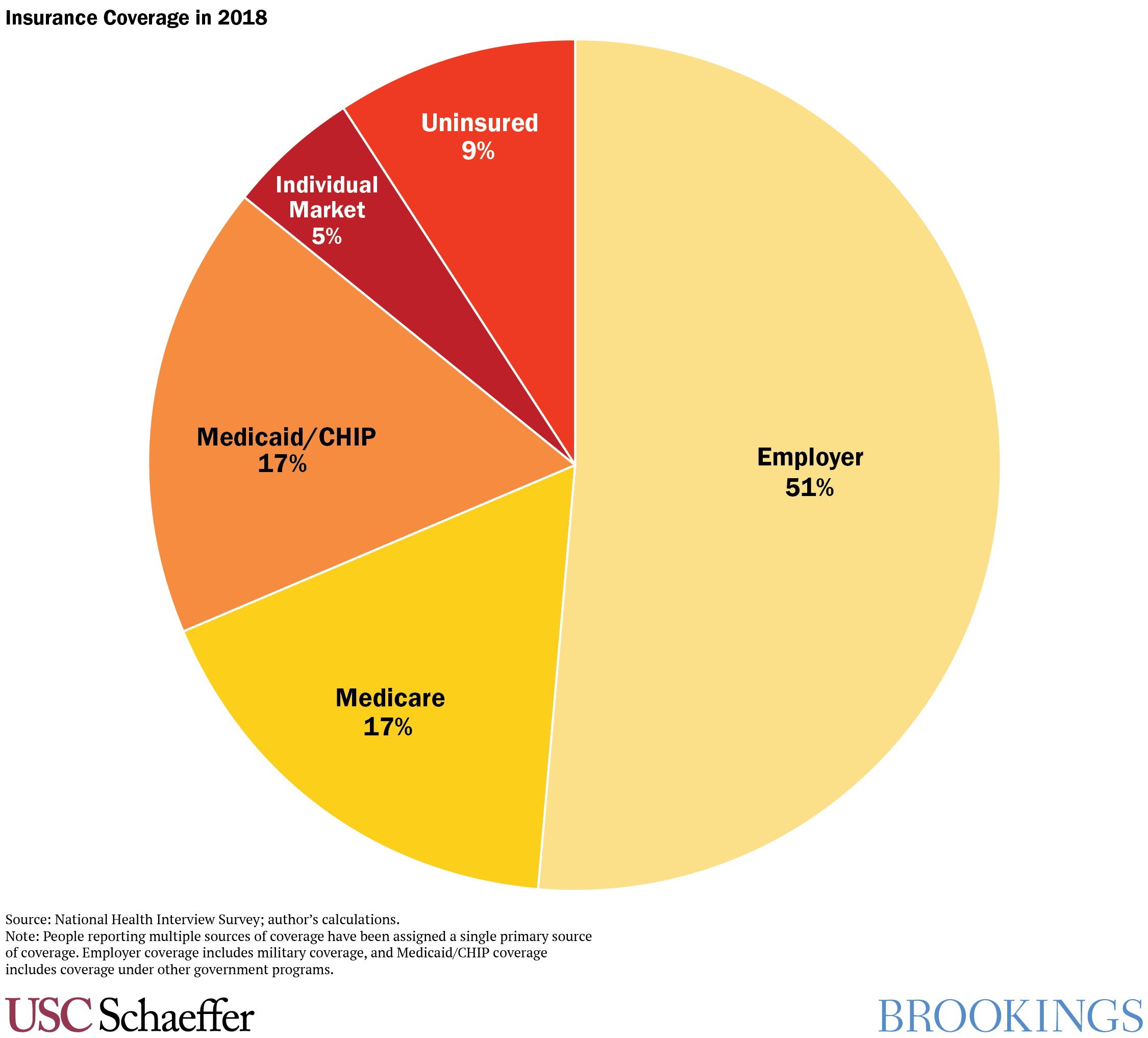

Today, more

than 90% of Americans have health

insurance. Slightly more than half of Americans have coverage through their own

job or a family member’s. Another 17% have coverage through Medicare, a federal

program that covers seniors and some people with disabilities, while 17% have

coverage through Medicaid, a joint state-federal program that covers low-income

people. Around 5% buy coverage on the individual market, either through the Marketplaces

established by the ACA or directly from an insurance company. About 9% of

Americans—almost 30 million people—have no insurance. The share of Americans without

insurance has fallen by more than two-fifths since enactment of the ACA, largely because the

law expanded Medicaid to more low-income people and created financial

assistance for most people who purchase individual market coverage.

These numbers represent a point in time, but individuals’ coverage

status changes over time; people

with insurance today can become uninsured or obtain coverage from another

source in the future, while currently uninsured people may gain coverage. This

means that a person interested in understanding how a policy would affect them must

consider not just what coverage they have today, but also what they might have

in the future.

Almost everyone who currently has insurance receives some form of public subsidy for that coverage. The federal government covers around 85% of the cost of Medicare, state and federal governments together cover nearly the full cost of Medicaid, and most people who purchase individual market coverage receive federal subsidies under the ACA. Even people who get coverage at work receive a substantial federal subsidy. Unlike wages, compensation in the form of health insurance is excluded from income and payroll taxation, which reduces the effective cost of job-based coverage by more than 30% on average.

Without these subsidies, many fewer people would have insurance in large part because insurance is so expensive. In 2018, the average annual premium for employer coverage for a single worker (including employer and employee contributions) was $6,900, and the average annual premium per person buying coverage on the individual market was similar. Indeed, even with existing subsidies, many insured Americans report being worried about their ability to afford premiums, deductibles, and other cost-sharing.

How would proposals to make federal coverage programs less generous affect health care coverage?

One commonly discussed set of proposals, supported by President

Trump and many Republicans in Congress, would reduce federal funding for programs

that subsidize coverage for low- and middle-income people and eliminate certain

regulations that apply to private insurers. In general, these proposals would

reduce federal spending on health care, but increase the number of uninsured

people and increase costs for sick people while lowering costs for some healthy

people.

President Trump’s proposals, which were

included in his 2020 budget and are modeled after proposals supported by many congressional

Republicans during the 2017 debate over repealing the ACA, have three primary parts:

- Repealing ACA coverage programs: President Trump proposes eliminating the parts of the ACA that provide financial assistance to people who buy individual market coverage, as well as the ACA’s funding for states that expand Medicaid. His proposal would replace those programs with grants to states that they can use to support health coverage, but the grants would offer significantly less funding than the ACA. The administration has argued that states would use funding more efficiently than the federal government, but it is likely that the overall reduction in funding would result in a large increase in the number of uninsured, consistent with analysis of a related proposal from 2017.

- Eliminating regulations

on health insurance: The Trump administration also supports allowing states to

eliminate regulations that bar private insurers from taking an individual’s

pre-existing conditions into account when setting premiums or coverage terms

and that require insurers to cover certain services. Eliminating these

regulations would allow insurers to offer cheaper plans, particularly to

healthier people, which could increase the overall number of people with some

coverage but would generally increase premiums and cost-sharing for sicker

people.

- Limiting funding

for Medicaid: Another proposal is to limit federal funding for the Medicaid

program. Currently, the federal government contributes a fraction (62%, on

average, in 2017) of each dollar a state spends on its Medicaid program. President

Trump would change this arrangement so that the federal government would

contribute a fixed amount that would be smaller than under current law. This is

referred to as a “block grant” or “per capita cap” depending on whether a

state’s federal contribution is fixed or varies as the number of people covered

by the state’s program varies. The reduction in federal funding would cause

states to make changes to their Medicaid programs, including reducing the

amounts they pay to medical providers, reducing what services they cover, and

reducing the number of people covered.

Congress has not enacted the administration’s

proposals, although many Republican members of Congress continue to express

interest in proposals like these. In response, the Trump administration has

sought to achieve similar objectives in other ways. Most importantly, President

Trump and 18 state attorneys general are participating in a lawsuit arguing

that the entire Affordable Care Act should be struck down by federal courts. If

successful, this would eliminate everything in the law, including the policies

that help people get insurance. Researchers at the Urban Institute estimate that this step would increase the number of

uninsured by 20 million. The Trump administration has also taken executive

actions. For instance, the administration has allowed insurers to offer plans that

do not provide comprehensive benefits and for which premiums can vary based on an

individual’s pre-existing conditions.

How would proposals to create a single payer system change health care coverage?

Unlike policymakers who are focused on reducing spending, most

Democratic candidates and elected officials support policies that would expand

government programs (and spending) to cover some or all of the remaining

uninsured. Some Democratic candidates and elected officials support creating a

“single payer” health care system that would cover everyone through a single,

unified program, rather than the patchwork of coverage sources we have today.

A prominent single-payer proposal is Senator Bernie Sanders’

“Medicare for All” bill, which would cover

almost all health care services and require no deductibles or cost-sharing,

although alternative proposals could cover narrower packages of services and include

modest cost-sharing. Under Senator Sanders’ proposal, the government would administer

benefits and pay providers, as in traditional Medicare. Some related proposals would

allow enrollees to elect to receive their benefits through a private insurer, as

Medicare enrollees can today through the Medicare Advantage program. While

these proposals are arguably not true “single payer” proposals, they have the

common feature that all Americans would receive their coverage through a single

program financed by the federal government.

A single payer system has potential benefits. It would be

dramatically simpler than the current system and ensure that no one remains

uninsured. A single payer system, as envisioned by its proponents, would also eliminate

premiums and greatly reduce cost-sharing for most families. Such a system would

also likely pay lower prices to health care providers and pharmaceutical

manufacturers and could reduce administrative costs, thereby putting downward

pressure on overall health care spending.

Single payer proposals would, however, substantially increase spending by the federal government. An analysis by the Urban Institute estimated that, if implemented in 2017, a single payer system along the lines of the Sanders proposal would have increased federal spending by $2.5 trillion, after accounting for savings from redirecting spending from existing health care programs, equivalent to almost two-thirds of all federal spending in that year. That increase in spending could be financed by increasing revenues and reducing spending on other programs. The net effects for any specific family would depend on the details of how a single payer system was financed and a family’s circumstances; some families might pay higher taxes but save money overall because they no longer pay premiums and cost-sharing, while others would pay more overall.

Transitioning to a single payer system would also have other consequences. It would, by design, require many Americans—including the 51% of people who get coverage through their employer—to change how they get coverage. Supporters of single payer proposals believe that most Americans would prefer the new system to the status quo, but the transition could be bumpy and polls show that voters are concerned about disruption. Reducing the prices paid to health care providers and pharmaceutical manufacturers could spur providers to become more efficient, but could also reduce quality or reduce pharmaceutical manufacturers’ incentives to develop new medications. The magnitude of those effects is uncertain and would depend on the prices paid under a single payer system.

What alternatives to a single payer system could expand health care coverage?

Not all Democrats have embraced single payer proposals, and even many

single payer supporters also support more limited proposals. Rather than trying

to transform the way all Americans get insurance, these proposals focus on people

who remain uninsured or face particularly high costs today. They generally are

designed to allow existing employer coverage to remain in effect.

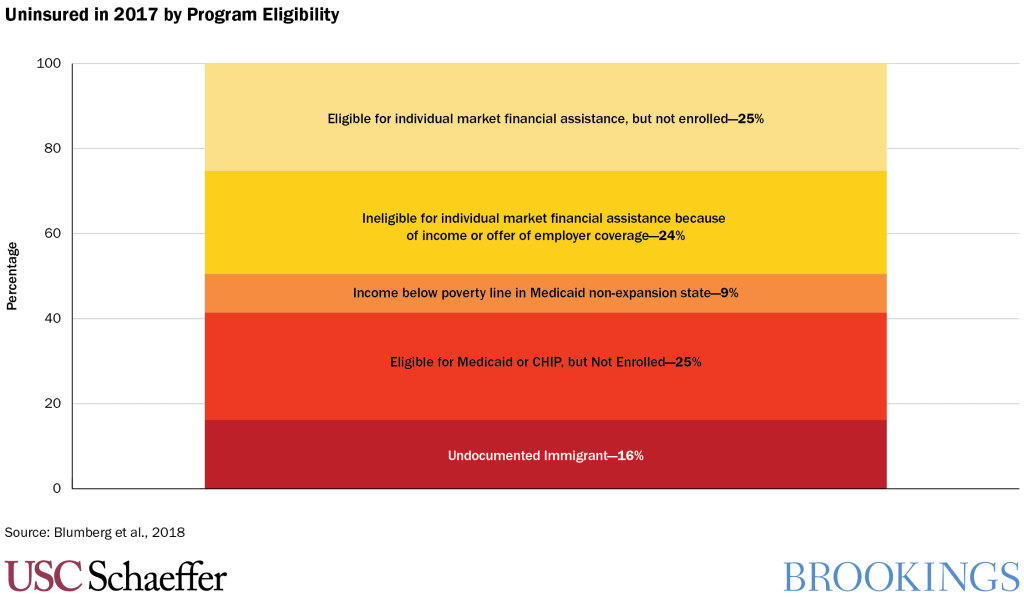

These proposals are more varied than single payer proposals. In

general, however, they aim to increase coverage among specific groups of

uninsured individuals depicted in the chart below, which draws on estimates by researchers

at the Urban Institute. Common steps include:

- Increasing and expanding eligibility for individual market financial

assistance: Many proposals increase and broaden eligibility for financial

assistance to buy individual market coverage. Steps like these would reduce

costs for the 5% of Americans who buy individual market coverage and reduce the

cost of coverage for about half the uninsured.

- Covering people in states that did not expand Medicaid: Some people are

uninsured because their state has not used ACA funding to expand Medicaid to

all low-income people. Policymakers could ensure this population gets coverage by

creating a new federal program or by creating additional financial

incentives for states to expand Medicaid.

- Encouraging people to take up coverage for which they are eligible: Some people are uninsured because they have not enrolled in low-cost coverage for which they are eligible. While some of these people may be induced to enroll by increases in financial assistance, many proposals also take other steps to encourage these individuals to enroll like funding additional outreach or automatically enrolling people in coverage.

- Addressing the undocumented population: About one-sixth of the uninsured are undocumented immigrants. Some envision covering this group by creating a pathway to citizenship for undocumented immigrants, which would ultimately make them eligible for existing coverage programs. Other approaches would expand the circumstances under which undocumented immigrants qualify for these programs.

Many Democratic proposals would also introduce a “public option,”

a government-run insurance plan that is offered alongside current private

insurance plans. In many proposals, the public option would be modeled on

Medicare and could pay providers less for delivering health care services than

private insurance plans, as Medicare does.

If the public option did pay providers less than private plans,

premiums for the public plan would likely be lower than the premiums of existing

private plans. Furthermore, the presence of a public plan might also enable

private insurers to negotiate better rates with providers, reducing premiums

for private plans as well. That said, the public option might be less effective

in utilization and care management, which could cut against any cost-savings.

Proposals differ in who would be eligible to purchase the public plan. Some proposals offer the public option only to consumers who would otherwise buy coverage on the individual market. Other proposals use the public option to cover some people who are currently covered by Medicaid (or who would be covered if their state expanded Medicaid). Some proposals go further and allow employers to purchase the public plan for their employees or allow people who are offered employer coverage to instead buy the public plan. These proposals seek to avoid the disruption of a single payer system that would require everyone with employer coverage to shift, but still allow those who want to shift to do so.

As under a single payer proposal, reducing the prices paid to health care providers and pharmaceutical manufacturers would cause changes in health care markets, including changing how providers deliver care and how manufacturers develop drugs. Once again, the nature of those effects would depend on the prices the public option pays and the breadth of the eligible population.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).

Commentary

What would the 2020 candidates’ proposals mean for health care coverage?

October 15, 2019