With President Obama’s last budget proposal headed for Capitol Hill this week, there will be little drama concerning defense. Last year’s Bipartisan Budget Deal predetermined the big decision—or at least most of it—on overall resource levels for the nation’s armed forces.

Counting nuclear weapons activities at the Department of Energy as well, national defense funds will tick up ever so slightly from $607 billion this year to $610 billion next year. Congress may adjust that latter figure upward modestly to account for new initiatives mentioned last week by Secretary of Defense Ash Carter—about $5 billion in additional funds for the fight against ISIS and for deterrence of Vladimir Putin. But in big-picture terms, the decisions seem to be already made.

Thus, the next truly interesting debates about America’s defense budget will likely play out on the presidential campaign trail. This is a debate we need. It is not, however, a debate that we are yet having—at least not in serious terms.

The sky is not falling

Some Republican candidates have complained about an American military in decline—or even one that has supposedly been “eviscerated” or “destroyed” by President Obama.

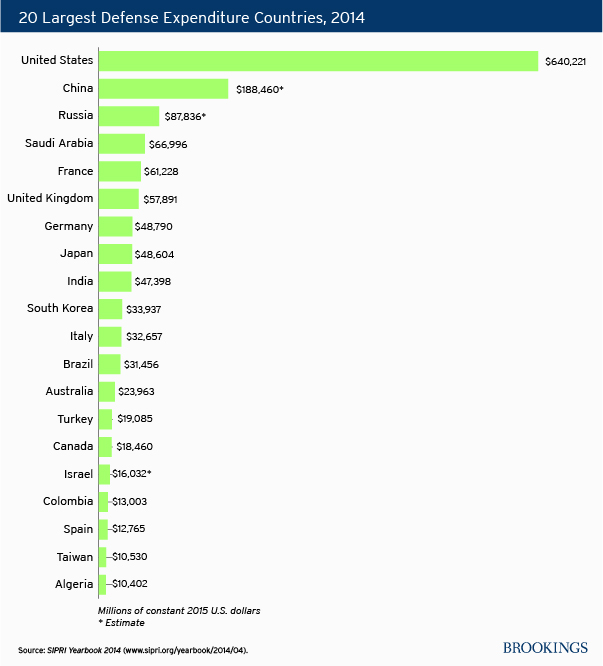

A few basic figures should help calm down the hyperbole. America’s current national defense budget of just over $600 billion a year exceeds the Cold War average for the United States of about $525 billion in those same, constant 2016 dollars. It greatly exceeds the year 2000 level, just before the 9/11 attacks, of some $400 billion. The U.S. national defense budget, which does not include budgets for Veterans Affairs or the Department of Homeland Security, remains a full 35 percent of world military spending. America’s allies and close friends account for almost another 35 percent between them, meaning that the Western alliance system wields the preponderance of global military resources even in the context of China’s rise and Russia’s revanchism.

[T]he Western alliance system wields the preponderance of global military resources even in the context of China’s rise and Russia’s revanchism.

Individual parts of the defense budget are reasonably healthy, too. Military compensation easily exceeds the average for the American workforce for individuals of given age, education, and experience across the preponderance of military specialties. Weapons budgets are not quite what they were under Ronald Reagan. But they do exceed $100 billion a year—a reasonably healthy and sustainable level. The so-called “procurement holiday” of the 1990s and early 2000s is over. Funds for training are roughly adequate for the size of the force, akin to Reagan-era levels as well in terms of flight hours, steaming days, major ground exercises, and the like.

Some point out that defense spending from 2011 through 2020 has been cut by a cumulative total of about $1 trillion already. That is true. But defense spending needed to go down from where it had been. The United States was spending more than $750 billion annually on national defense over the 2008 to 2011 period. That level easily exceeded the real-dollar peaks of the Reagan buildup, Vietnam War, and Korean War. It was more than is needed today; that late Bush/early Obama period should not be retroactively defined as the gold standard in defense spending or strategy.

Have we got what we need?

That said, hawks are right that a debate is needed about certain specific unmet needs in Pentagon accounts. U.S. military spending may well be, as President Obama noted in his January State of the Union address, equal to the next eight highest-spending countries combined. But defense budgets do not always dictate combat outcomes, or ensure effective deterrence. Chinese precision missiles, Russian advanced air defenses, and other such assets—whether operated by Beijing and Moscow or sold to other parties—can cause asymmetric, disproportionate effects. New technologies offer promise for America’s armed forces, but also new ways for adversaries to challenge or hurt the United States—as such, it is important for the Department of Defense to have enough resources to pursue modernization itself, and respond to real or anticipated innovations by others.

[D]efense budgets do not always dictate combat outcomes, or ensure effective deterrence.

U.S. military spending is indeed great. But it is now only about three times that of China, after having been nearly 10 times larger at the turn of the century. That 3:1 edge may sound like a comfortable advantage. It is not, especially when the correct strategic goal for the United States is not primarily to defeat China in combat but rather to deter combat in the first place. China has the luxury of being able to concentrate its strategic energies on the Western Pacific region alone. For America, its responsibilities go much further. And while America’s allies are wealthy and numerous in many cases, they have not kept their military spending levels as high as most had promised, and they have not always spent their resources well.

U.S. defense spending as a percent of the economy, as noted, is down to about 3 percent of GDP, after having reached nearly 5 percent in the latter Bush and early Obama years—and after approaching 6 percent under Ronald Reagan and averaging around 8 percent in the latter 1950s and 1960s. That 3 percent figure is much less relative to the size of the economy than was the case even in the days of the “hollow Army” of the post-Vietnam 1970s. Also, today’s U.S. military of some 1.3 million active-duty uniformed personnel is much smaller than the Cold War force that exceeded 2 million during its latter decades.

It is also smaller than China’s and not much bigger than the Indian or North Korean militaries, by way of comparison. High personnel costs, while appropriate for an all-volunteer force that must be excellent to compensate for its modest size, do sometimes crowd out funds for investment. A decade of national budgetary shenanigans such as sequestration, overlapping with a decade and a half of war, have taken a toll on the American armed forces as well.

A decade of national budgetary shenanigans such as sequestration, overlapping with a decade and a half of war, have taken a toll on the American armed forces.

Three ideas

Put this together and I would hope that presidential candidates would discuss and debate three main themes beyond the immediate issue mentioned above of ensuring adequate war funding in 2017 and beyond. Each could involve the added expenditure of roughly $10 billion to $15 billion a year; in other words, if all of them were made, we could wind up with a steady-state military budget perhaps $30 billion to $40 billion higher than now planned. Consider:

- We could end an era of cuts to the active-duty Army that dates back to the early Obama years. Rather than keep cutting the Army, already 100,000 soldiers smaller than a decade ago and modestly smaller than it was in the Clinton years, we could hold the line or even modestly add back some troops.

- The Navy could ensure that it has enough ships in the Western Pacific to give military backbone to President Obama’s half-forgotten Asia-Pacific “rebalance.” This could be done in part by economies and efficiencies in how the Navy allocates its global resources; it could also be facilitated by a temporary increase in the shipbuilding budget of several vessels a year (from the current average of about nine).

- More generally, other modernization accounts in the U.S. military could be more adequately funded. There may be room for some cutbacks in existing plans, as with the F-35 fighter and next-generation nuclear missile submarine, and perhaps even the aircraft carrier fleet. But there are other, unmet needs ranging from underwater robotics to new missile defense technologies to hardened and resilient space and cyber assets that require more resources than they have recently received.

Our national defense debate need not be overly stark or alarmist this year. Today’s U.S. military, while rather small, is excellent, and its men and women are doing their jobs extremely well, with resource levels generally in the ballpark of what is needed for the tasks at hand. That said, there are some specific gaps—and it would be wise of the candidates on both sides of the aisle to start addressing them.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).

Commentary

What the next president needs to think about on defense strategy

February 10, 2016