In May, the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) and the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers (USACE) finalized a long-debated clean water rule to limit pollution in a variety of streams, tributaries, and wetlands. Aiming to clarify what types of waters receive protection under the 1972 Clean Water Act, the rule offers greater regulatory certainty concerning upstream resources—critical to water quality—and marks a departure from the time-consuming, case-by-case regulatory process currently in place.

Not surprisingly, the new rule has triggered a national political firestorm focused on the measure’s legal jurisdiction and EPA’s potential overreach, issues previously raised in two Supreme Court cases, but more salient questions loom over the rule’s long-term environmental impact at the state and local level. The rule will also have a number of economic implications for developers, utilities, and farmers, among numerous other public and private actors.

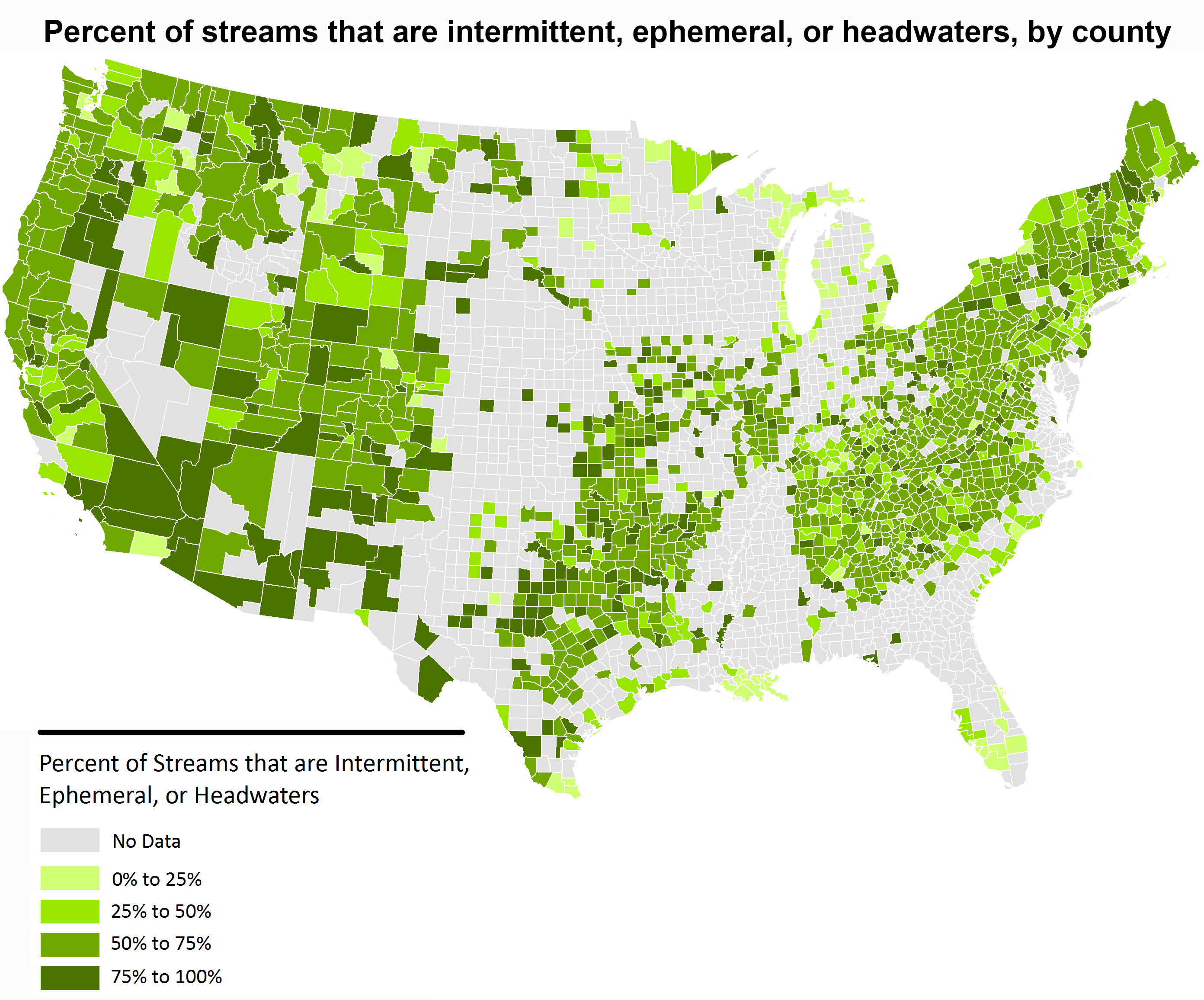

Almost 60 percent (207,000 miles) of the nation’s streams are expected to gain clearer protection from the new rule, particularly those that are seasonal and rain-dependent. In some areas, more than three-quarters of all streams, by mileage, can fall into this “intermittent, ephemeral, or headwaters” category. From drought-stricken parts of California and Arizona to Tennessee and Pennsylvania, these streams serve as a crucial source of water for irrigation, manufacturing, and recreation.

Source: Brookings analysis of Environmental Protection Agency data

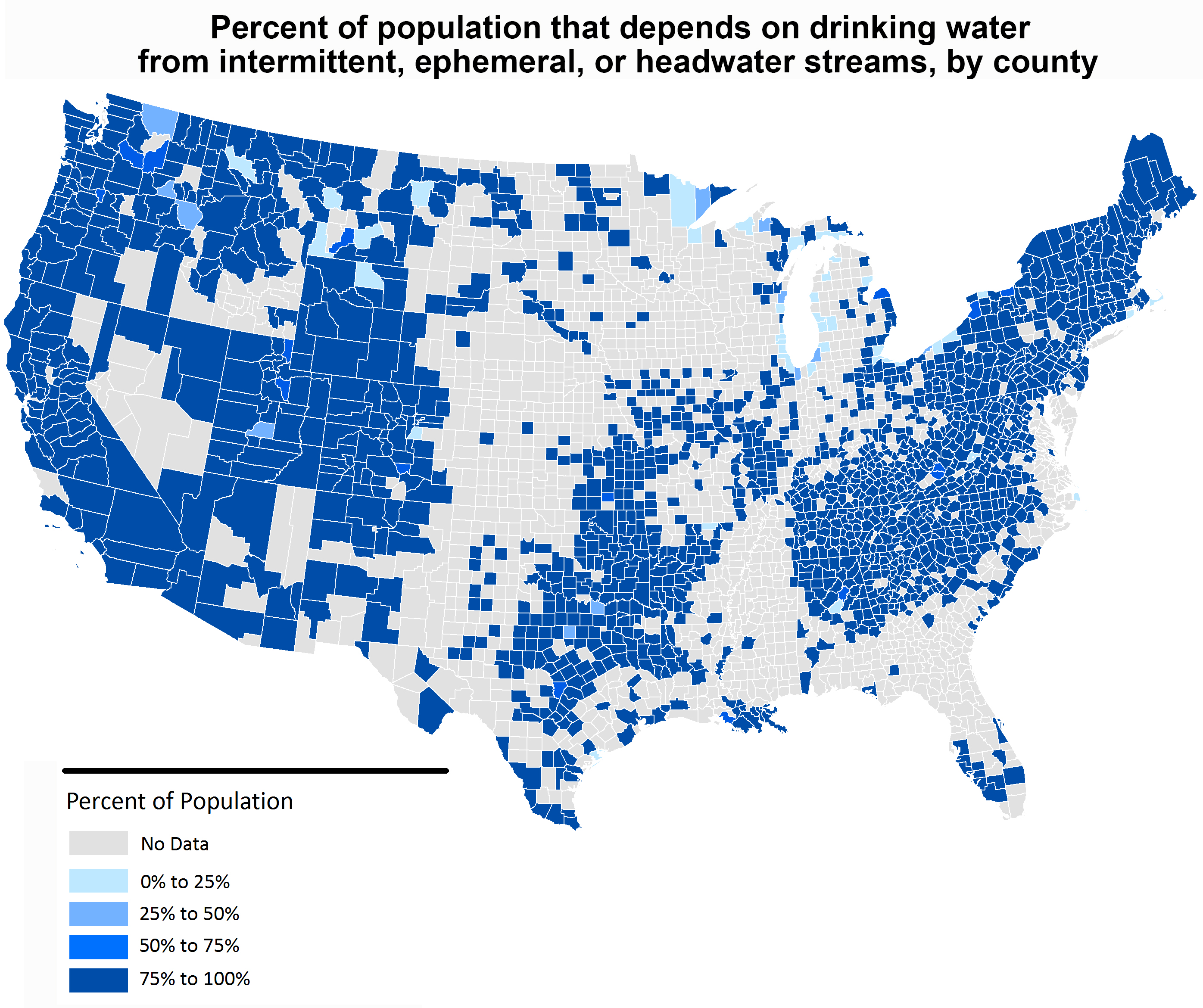

Note: Includes public surface drinking water from intermittent, ephemeral, and headwater streams

In most localities, these intermittent, ephemeral, or headwater streams also represent a vital source for public drinking water. Nearly 117 million people across almost every region of the country get drinking water at least partially from these streams and stand to benefit from safer, cleaner sources. The streams stretch not only across rural expanses of the Midwest but also into several large East and West Coast markets like New York and Seattle, where 90 percent or more of the population depends on such sources for their public drinking water.

Source: Brookings analysis of Environmental Protection Agency data

Note: Includes public surface drinking water from intermittent, ephemeral, and headwater streams

By increasing transparency over what waters are covered under the Clean Water Act, the new rule helps address quality concerns for consumers, especially in vulnerable areas like Toledo. In addition, EPA and USACE estimate that a wide range of direct and indirect benefits could total up to $514 million annually, despite additional permitting costs likely borne by local governments and private entities. Supported by these safeguards, regions can gain access to cleaner, more efficient sources of water, boosting their resilience and economic competitiveness over time.

Commentary

What the new clean water rule means for metro areas

June 10, 2015