This piece was originally published in March 2023. It has since been updated to reflect ongoing developments.

In March 2023, the Federal Reserve responded quickly to the failures of Silicon Valley Bank (SVB) and Signature Bank. It joined other regulators in lifting the $250,000 per account deposit insurance for customers of those two banks, described in more detail in “How does deposit insurance work?” This explainer describes other steps the Fed took.

What is a lender of last resort?

Banks, in general, take deposits from their customers (who often can take their money out whenever they want) and put the money into loans or securities (often longer-term commitments that sometimes cannot be easily sold). In normal times, when most depositors are content to leave their money in the bank, this works well. Banks are required by law to maintain a portion of deposits in cash so that they can meet customer demands for withdrawal.

However, if depositors withdraw a lot of money at once, the bank may not have enough cash on hand to satisfy them. This can happen if depositors lose confidence in the bank’s ability to meet all withdrawal demands so every depositor tries to be at the head of the line – a run on the bank, a phenomenon explained by economists Douglas Diamond and Philip Dybvig for which they shared a Nobel Prize in 2022. If the bank cannot borrow money, it may be forced to call its loans or sell other assets quickly, sometimes at a loss, to raise cash. A lender of last resort – a central bank like the Federal Reserve – provides loans to banks so they can meet depositor demands. The banks pledge collateral – bonds, loans or other assets – so the central bank isn’t at risk of losing money.

What is the Bank Term Funding Program?

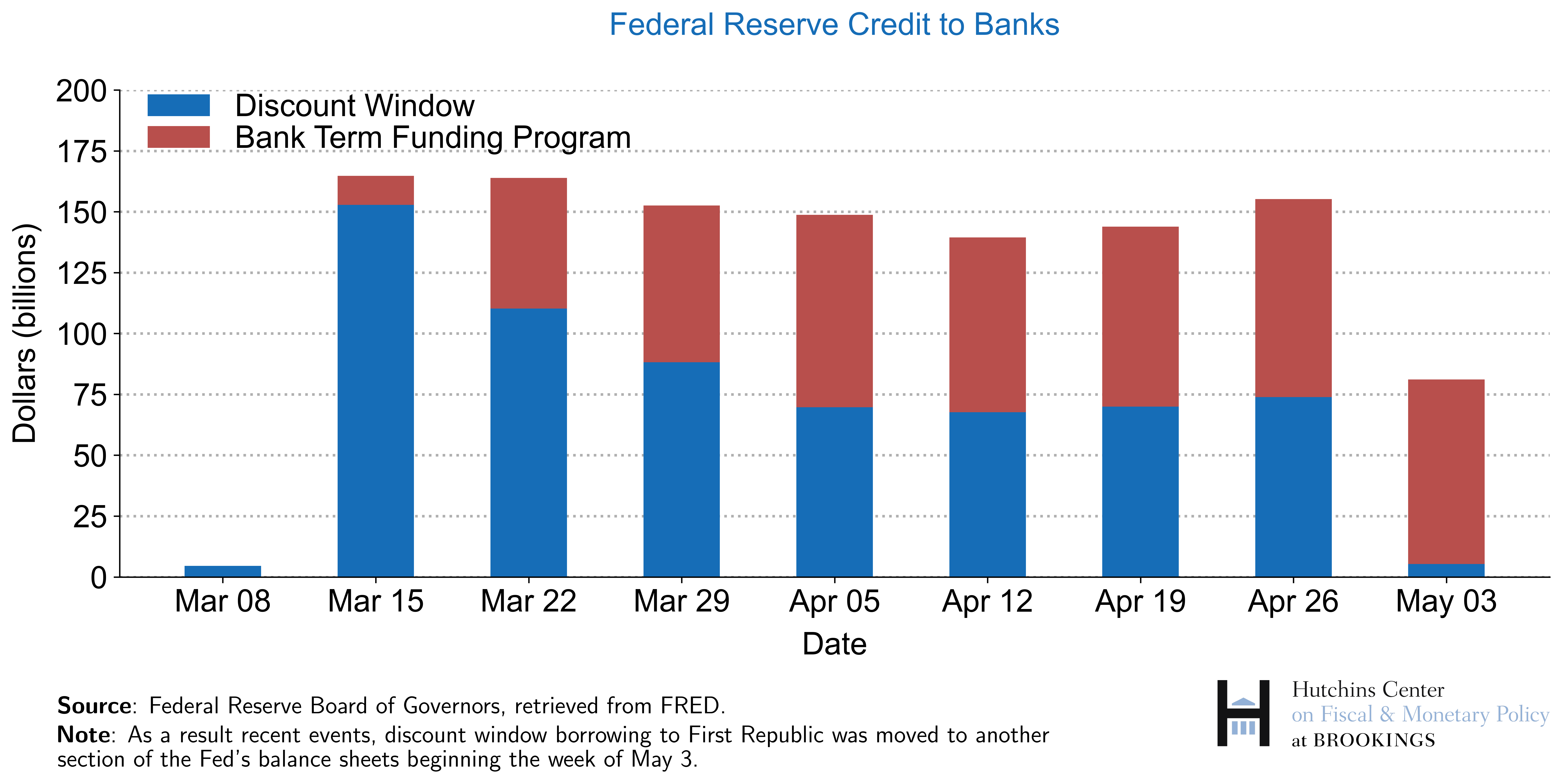

The Bank Term Funding Program (BTFP) is a lender of last resort facility. It was created in March 2023, after the failures of Silicon Valley Bank and Signature Bank, to lend to other banks that had big unrealized losses on their holdings of government bonds and were, therefore, at risk of large-scale withdrawals of deposits. The facility allows banks to exchange assets such as U.S. Treasuries for cash at their full-face amount, regardless of the current market value. These loans are for up to one year at an interest rate equal to the one-year overnight index swap (OIS) rate, plus 0.10 percentage points. This rate varies daily. As of April 28, the BTFP rate was 4.92%. As of May 8, the BTFP rate was 4.81%. As of May 3, banks borrowed $75.8 billion through the Bank Term Funding Program, down from $81.3 billion the week before.

The Treasury has earmarked $25 billion to backstop the BTFP, but the Fed said it does not anticipate it will have to draw on that.

The Fed said in January 2024 that the BTFP would stop making loans, as scheduled, on March 11, 2024. It also adjusted the interest rate on any new loans to be no lower than the interest rate that the Fed pays on bank reserves. Until that change, some banks borrowed heavily at the BTFP and deposited the funds as reserves at the Fed at a higher interest rate to make a profit. As that maneuver became more attractive, bank borrowing from the program rose from about $100 billion in June 2023 to $161.5 billion in mid-January 2024.

What is the discount window?

The Fed traditionally exercises its lender of last resort function through the discount window, a permanent facility that lends cash to banks, often for just a few days or weeks. The banks pledge collateral to the Fed but, unlike the BTFP, the Fed will not lend against the full-face value of the bond or loan; instead, it lends up to the market value of the security or loans and, in some cases, takes what’s known as a haircut to make sure the collateral is sufficient to cover the loan. Until recently, the Fed imposed a haircut between 1% and 5% on Treasuries, agency debt (Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac), and mortgage-backed securities, but it eliminated those haircuts after the Silicon Valley Bank collapse. The discount rate, the interest that banks pay on these loans, is set by the Federal Reserve Board.

The discount rate, the interest that banks pay on these loans, is set by the Federal Reserve Board. As of May 8, it was 5.25%.

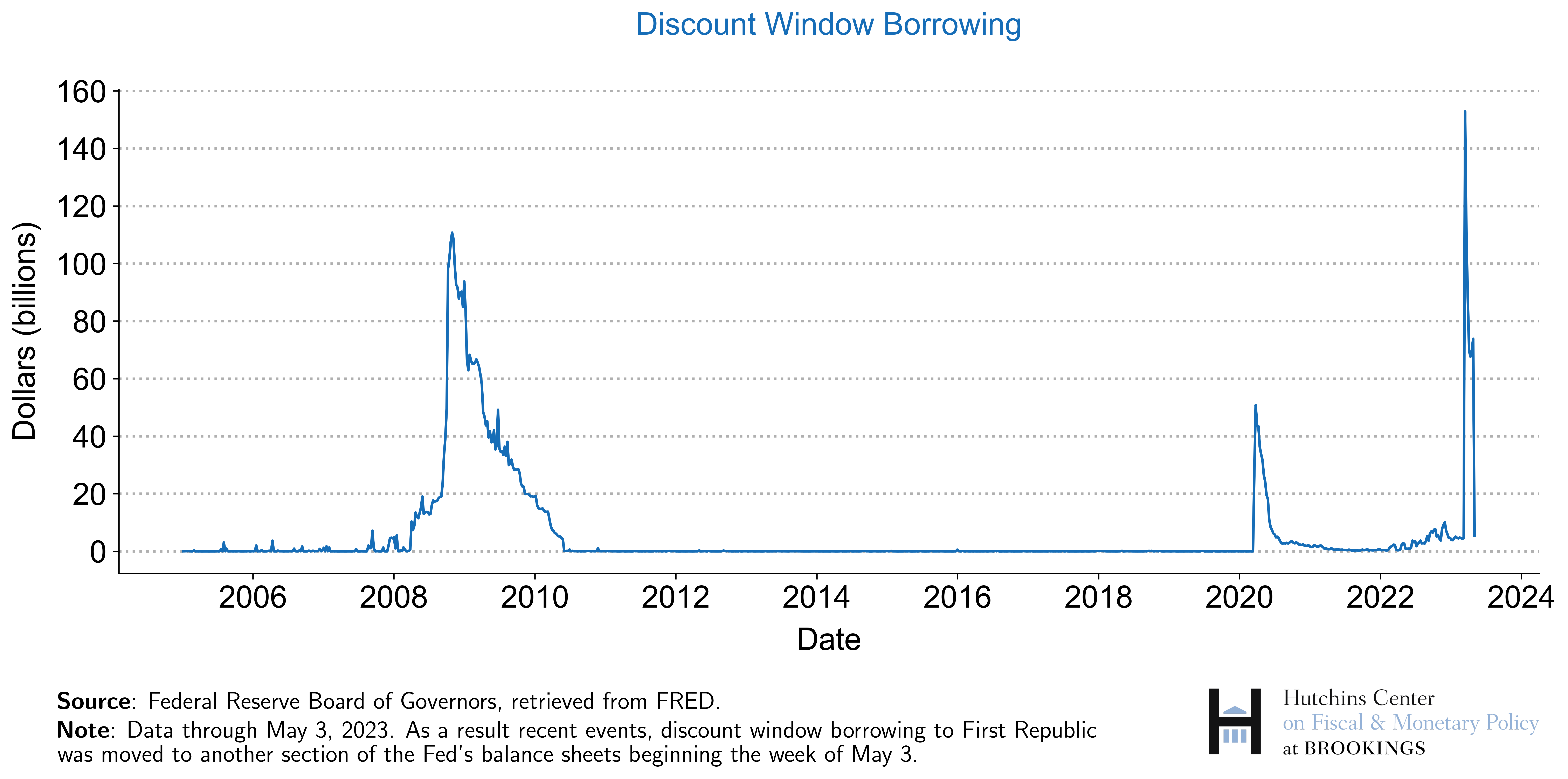

Banks are sometimes reluctant to borrow at the discount window because, if word gets out, it may suggest that the bank is in trouble. Borrowing at the discount window soared from $4.6 billion on March 9 to $152.9 billion on March 15 and fell to $67.6 billion on April 12. This decrease was largely offset by increased borrowing through the Bank Term Funding Program. As of May 3, discount window borrowing was $5.3 billion, down sharply from $73.9 billion the week before, because the Fed’s substantial loans to First Republic were moved to another category on the Fed’s books—one that consists of loans to banks that have been taken over by the FDIC, including SVB, Signature Bank, and First Republic. These loans totaled $228.2 billion as of May 3.

The Bank Policy Institute, which represents U.S. banks, speculated that borrowing at the discount window was heavier than at the BTFP because banks had pre-positioned collateral at the discount window or because they were simply more familiar with borrowing at the discount window than through the new facility.

What are swap lines?

Many banks overseas borrow and lend in U.S. dollars. At times of financial stress, foreign banks often face demands for U.S. dollars that they can’t easily meet. Foreign central banks can print their own currencies – euros, yen, Swiss francs, British pounds – to lend to their cash-strapped banks, but they can’t print U.S. dollars. During the Global Financial Crisis, the Fed began a series of agreements with foreign central banks under which the Fed would swap U.S. dollars for foreign currencies with other central banks; the foreign central banks pay interest to the Fed. At the program’s peak, swaps totaled more than $580 billion, more than a quarter of all the Fed’s assets. Until March 2023, the Fed conducted these swaps once a week. As of May 3, the Fed had $410 million in these swaps outstanding. On March 19, 2023, it said it would begin daily swaps at least through the end of April “to improve the swap lines’ effectiveness.”

What about interest rates?

On March 22, the Fed raised its target for short-term interest rates by another ¼ percentage point to a range of 4.75% to 5%, but it significantly changed its guidance on future interest rates moves. Fed Chair Jerome Powell said in his press conference: “[W]e no longer state that we anticipate that ongoing rate increases will be appropriate to quell inflation; instead, we now anticipate that some additional policy firming may be appropriate.” In its statement, the Fed’s policy committee said, “The U.S. banking system is sound and resilient. Recent developments are likely to result in tighter credit conditions for households and businesses and to weigh on economic activity, hiring, and inflation. The extent of these effects is uncertain.”

What role did the Fed play in supervising Silicon Valley Bank?

The Federal Reserve – primarily the Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco – was Silicon Valley Bank’s primary regulator. Signature Bank, a New York bank that also failed in March, was regulated primarily by the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC). Both banks also were overseen by state regulators.

What did the Fed’s review of its supervision of SVB find?

On April 28, Vice Chair for Supervision Michael S. Barr released a lengthy review of the Fed’s supervision and regulation of SVB. The Fed highlighted four causes of the bank’s failure:

- SVB’s board of directors and management failed to manage their risks.

- Fed supervisors did not fully appreciate the extent of the vulnerabilities as SVB grew in size and complexity.

- When supervisors did identify vulnerabilities, they did not take sufficient steps to ensure that SVB fixed those problems quickly enough.

- The Federal Reserve Board’s response to a 2018 law—the Economic Growth, Regulatory Relief, and Consumer Protection Act, which lightened the oversight of some mid-sized banks—and the shift in top Fed policymakers’ guidance to supervisors impeded effective supervision by reducing standards, increasing complexity, and promoting a less assertive supervisory approach.

-

Acknowledgements and disclosures

The Brookings Institution is financed through the support of a diverse array of foundations, corporations, governments, individuals, as well as an endowment. A list of donors can be found in our annual reports published online here. The findings, interpretations, and conclusions in this report are solely those of its author(s) and are not influenced by any donation.

Commentary

What did the Fed do after Silicon Valley Bank and Signature Bank failed?

January 25, 2024