Those who liked President Trump’s inaugural address last January and his speech to the Republican National Convention in July 2016 will find much to applaud in the National Security Strategy (NSS) his administration published on December 18. Like Trump’s speeches, the NSS describes a world inhabited by hostile forces that threaten American well-being, and it sees America’s future identity, prosperity, and security as largely based on our ability to wall them out, out-compete them, or defeat them militarily. There are some nods to cooperating with allies and like-minded states, and brief references to defense of American values abroad, but these are minor themes compared to the drumbeat about triumphing over others in a competitive world.

One old Trump theme, ignored since his inauguration, that finds new precision and emphasis in the NSS is the characterization of China. It is described as “challenging American power, influence, and interests, attempting to erode American security and prosperity.” This competition will

“require the United States to rethink the policies of the past two decades—policies based on the assumption that engagement with rivals and their inclusion in international institutions and global commerce would turn them into benign actors and trustworthy partners. For the most part, this premise turned out to be false.”

This description is a mixture of truisms, appropriate exhortations, dubious analysis, and bad history.

This description is a mixture of truisms, appropriate exhortations, dubious analysis, and bad history.

On the positive side, the NSS is correct that China is challenging American power, influence, and interests, and this competition will require the United States to rethink its policies. China’s challenge does risk erosion of American security and prosperity if misjudged, misinterpreted, and mishandled.

But what does the NSS mean when it says the premise of U.S. policy—that China’s inclusion in institutions and commerce would make it benign and trustworthy—has been mostly false? Logically, that would seem to suggest that China should be expelled from international institutions and its role in global commerce should be marginalized. Is that the Trump administration’s goal? Needless to say, neither objective will be achieved, in whole or in part. So is this simply a rhetorical device designed to validate the idea that engagement with China has led to unexpected and disastrous results, and needs to be jettisoned?

Virtually no senior officials in the Trump administration worked on U.S. relations with China during the period the NSS describes or before, so they do not know from first-hand experience what engagement has achieved. The brief review of accomplishments in the U.S.-PRC relationship that follows contradicts the NSS’s assessment, and suggests the need for considerable caution about the NSS’s vague prescription for what is now needed.

Reading the history

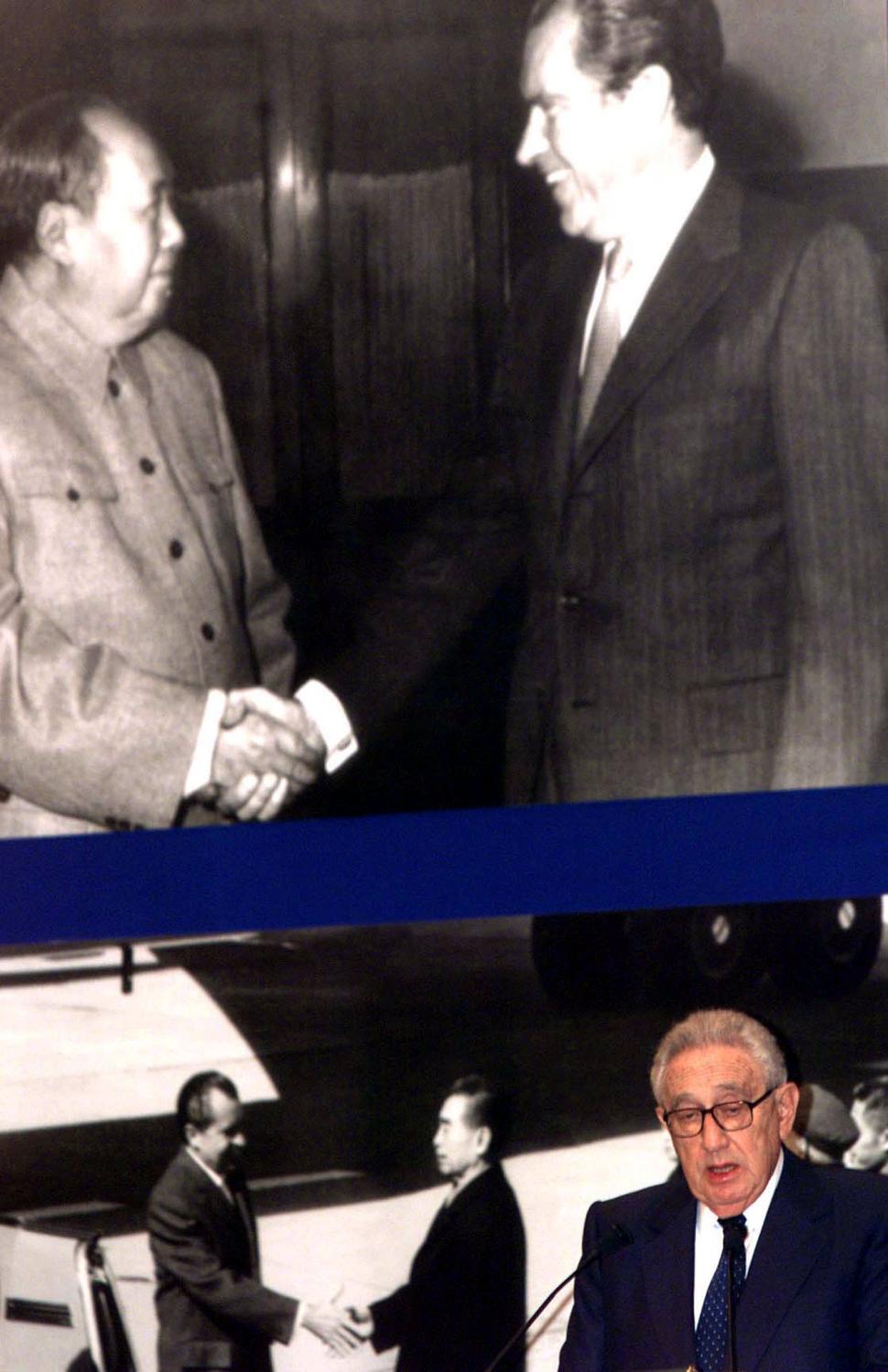

The fundamental U.S. objective in opening relations with China under President Nixon was to work in cooperation and in parallel with China to counter the Soviet Union. That remained the foundation of U.S.-China relations for close to two decades until the demise of the USSR.

After the collapse of the Soviet Union, the basis for U.S.-China relations altered. Trade and investment ties between the two sides have grown by leaps and bounds, though not without significant imbalances and problems. The need for cooperation on global issues increased dramatically with China’s growing strength, influence, and interest in issues outside its periphery. The United States also sought to enlist Chinese support for its positions on areas of international conflict, or at least to minimize Chinese opposition in areas where views differed.

At no point has U.S. policy toward China been based on some gauzy conception of a “benign” China that would sacrifice its interest for ours, adopt a political system modeled on Western values, or cease to be a difficult competitor. Policymakers have understood that the U.S.-China relationship would be a mixture of cooperation and competition, with the hope of maximizing the former and managing the latter so that it did not escalate into conflict. This realistic appraisal was a consistent underpinning of U.S. policy during the 1990s and early 2000s when Trump’s NSS asserts that naiveté guided American expectations.

An impressive list of achievements

What has been accomplished during the years of engagement based on “false premises” since relations were established?

- Nonproliferation. Until the late 1980s, China was the leading proliferator of weapons of mass destruction in the developing world, helping Pakistan develop nuclear weapons and offering ballistic missiles and associated technology to a host of countries in the Middle East. Beginning in the 1980s and continuing through the next two decades, China came to conform with global norms, and it now largely exercises control over export of WMD and associated technologies. It worked with the United States in 2015 to conclude the agreement freezing the Iranian nuclear program, after having been a nuclear partner of Iran until the mid-1990s. It worked with the Clinton and Bush administrations to try to freeze North Korea’s nuclear weapons program, and indeed President Trump has personally expressed pleasure with Beijing’s efforts to rein in North Korea. There is more Beijing can do vis-à-vis North Korea, but its behavior has changed markedly since it served as Pyongyang’s chief ally and enabler in the 1980s and early 1990s.

- International agreements on WMD. China ceased to conduct nuclear weapons tests in 1996 under pressure from the United States and the international community. It acceded to the Conventions on Biological Weapons and Chemical Weapons in the 1980s and 1990s, respectively. It signed the Comprehensive Test Ban Treaty on nuclear weapons, but has declined to ratify until the United States does so.

- Taiwan. There has been no military conflict in the Taiwan Strait since the late 1950s, despite China’s claim to sovereignty over Taiwan and determination to achieve reunification. Since Taiwan is widely seen as the issue most likely to lead to conflict between the United States and China, the management of the issue through a combination of agreements and communiqués, public policy, legislation, deterrence, and development of cross-Strait ties has been vital to peace. Successive U.S. administrations have understood that maintenance of a “one China” framework and overall sound U.S.-China relations are vital elements in maintaining stability in the Strait.

Economic relations. Much attention is focused on imbalances in U.S.-China trade relations, and rightly so. But we should not overlook the fact that China’s economy has become the largest contributor to global economic growth in the last decade, according to the World Bank; that it has expanded profits for leading U.S. companies; that China has become the fastest-growing major economy destination of U.S. exports in the last 15 years; that its government helped prevent a worldwide depression in 2008-2009 through its large stimulus package, which was developed in cooperation with Treasury Secretaries Paulson and Geithner; and that China acceded to the World Trade Organization (WTO), which helped it to become the world’s second-largest importing country. In the last few years, China has become a leading source of global foreign investment, of foreign assistance to Africa and Latin America, and of infrastructure development throughout the world, helping to stimulate economic growth.

Climate change. China passed the United States as the leading emitter of greenhouse gases within the last decade, but resisted the idea that it had any responsibility for restraining and reversing climate change until the Obama administration worked with it closely to alter its approach. China has now accepted that it must play a leading role in combating climate change, even if its commitments remain insufficient.

Use of force. The last time China engaged in substantial military conflict was with Vietnam in 1979, notwithstanding some dust-ups in the Spratly Islands that led to loss of lives in the 1980s. The other major powers, the United States and Russia, each have been involved in several military conflicts overseas during this period, claiming thousands of lives. China has relationships with a number of its neighbors—notably Taiwan, Japan, India, Vietnam—and various claimants in the South China Sea that run the risk of escalation. So Chinese military restraint is not automatic; it needs to be encouraged through a combination of bilateral and regional diplomacy, deterrence, American alliances and partnerships, and development of ties between China and its neighbors.

Cybersecurity. China has long engaged in theft of foreign intellectual property, including by means of cyberattacks. The Obama administration negotiated an understanding with Beijing under which the latter committed to refrain from government-sponsored cyber theft for commercial gain. The United States and China have held several meetings to implement this agreement, both under Presidents Obama and Trump. It has led to a noticeable drop-off in Chinese hacking of U.S. companies for commercial advantage.

Chinese relations with countries it formerly isolated. Until the 1990s, due to its legacy as a revolutionary power and third-world advocate, China was hostile to Israel and South Korea, siding with their enemies and refusing political and most economic relations with either. The United States for years urged China to develop relations with both, to play a constructive role in both regions, and, in the process, to diminish pressure on U.S. allies. China established diplomatic relations with both in 1992, and since then has played a more positive role in both regions, economically and politically.

China has now accepted that it must play a leading role in combating climate change.

This list of ways in which China has played a constructive international role in supporting U.S. interests is not meant to be a balanced assessment of Chinese conduct, but a refutation of the NSS assertion that engagement has failed to deliver meaningful results.

There have been substantial shortcomings in Chinese conduct in many of these areas, and U.S. policy must adjust to counter them. For example, China pursues mercantile policies that deviate significantly from the norms of other major countries and hurt our economy and our companies. The United States wishes China would increase pressure on North Korea. While it has not used lethal military force, China has pursued coercive policies in the East China Sea, the South China Sea, vis-à-vis Taiwan, and along the Line of Actual Control with India. Its foreign assistance programs, while a net contribution to global development, don’t do enough to protect against corruption, minimize environmental degradation, and offer transparency.

More fundamentally, China poses a challenge in its sheer accumulation of power, wealth, and influence in the last two decades. In parallel with its spectacular economic growth, China has significantly upgraded its military and can better advance its interests unilaterally and through multilateral organizations. The strategy of the Deng Xiaoping era—to be patient, bide its time, and not take international leadership—has been replaced by that of Xi Jinping, which highlights China’s ability and desire to play a larger role on the world stage and accept greater responsibility. Most of China’s neighbors, which have benefited greatly from Chinese economic growth and which would suffer from a trade war, are also anxious over Chinese security and military strategies that they see as threatening.

A fresh start, but from the right starting line

So the NSS is not wrong in concluding that the United States needs fresh thinking. But it would be wrong to do so without understanding what has been accomplished, with great exertion, by administrations of both political parties. None of these achievements happened automatically, all continue to be relevant for U.S. interests, and none will be sustained without persistent engagement.

The NSS puts the emphasis on competition, if not outright confrontation.

The NSS puts the emphasis on competition, if not outright confrontation. Interestingly, when not pontificating in strategy documents, Trump officials seem to understand the need for a mix of cooperation and competition. The background briefings by Trump administration officials about the NSS were markedly more positive about China, highlighting the need for cooperation. President Trump also regularly highlights the importance he places in his personal relationship with President Xi. So it is not altogether clear that the highly competitive, perhaps hostile, relationship with China that the NSS seems to prefigure is really where the Trump administration intends to go.

The strategic shape of the U.S.-China relationship going forward is a subject for another essay. The engagement of the four decades since normalization has never been considered a strategy by itself, but a means to an end. Pure engagement divorced of clear objectives would be even less acceptable. Other ideas—such as former deputy secretary of state Robert Zoellick’s “responsible stakeholdership” and the Obama administration’s stress on a China that lives up to international norms and rules—have continuing relevance, though they will not be self-executing. Former U.S. Secretary of State Henry Kissinger and former Prime Minister of Australia Kevin Rudd have talked about subsuming China along with the United States in a Pacific community, a goal that also could usefully inform diplomacy and statesmanship.

There will doubtless be heightened economic and commercial tensions between the United States and China. More ominously, there will be military competition and elements of an arms race. Chinese paranoia of the West is reinforcing domestic repression and tightening of Communist Party dominance of all institutions. In the West, there are incipient calls to resist Chinese infiltration and influence-peddling that can easily go overboard. The United States will face multiple challenges by a rising China, which the NSS has inflated without offering answers. Figuring these out will be a challenge not only for the Trump administration but also for outside foreign policy analysts. But the chances of success will be greater if there is an understanding of what has been accomplished, and not accomplished—not just a condemnation of Trump’s predecessors.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).

Commentary

Was pre-Trump U.S. policy towards China based on “false” premises?

China in Trump’s National Security Strategy

December 22, 2017