This is the sixth and final post in a series on federal disaster policy reforms. Previous posts outlined principles for reform; examined changes to the federal disaster declaration process; recommended improvements in the federal management system; explored the division of responsibilities between federal and state governments and the private sector; and suggested how to build the capacity of under-resourced local governments.

There are many stories about people who slip through cracks of our national disaster safety net. After Hurricane Katrina, testimonies were transmitted across broadcast and early social media about a fact that many families already know: The “system” was not designed to protect everyone from disasters, nor to make it easy for everyone to recover, leaving them in places where they may be vulnerable to repeating incidents.

The disaster cycle is debilitating, and occurs for vulnerable families of all kinds. For example, the family that lost a child when Hurricane Ida flooded their New York City basement apartment, which continues to flood today. Or the family that fled one disaster only to repeatedly move into the path of another, from Florida’s Hurricane Michael, through California’s wildfires, to this summer’s Vermont floods.

The multiple disasters of 2017 catalyzed demands for documenting who slips through these cracks. This led to calls for possible reforms: more federal intake centers, more survivor-friendly application processes, better case management, and increased transparency about the demography and geography of beneficiaries. These calls also extended to questions about which communities receive resources for building protections before disasters strike.

In the six years since, the legislative and executive branches have learned some lessons. Our disaster mitigation programs—such as the Federal Emergency Management Agency’s (FEMA) Building Resilient Infrastructure and Communities program—have been expanded and more equitably targeted. And the Department of Housing and Urban Development’s (HUD) long-standing focus on low- to moderate-income households and at-risk populations expanded with the Rapid Unsheltered Survivor Housing (RUSH) program.

But there are other lessons to be learned from how our federal safety net could better target disaster-specific aid. The response to the COVID-19 pandemic taught us that the federal government can help efficiently, effectively, and equitably. This included direct cash disbursements that kept at-risk and financially precarious households afloat. With these lessons, how can we reform disaster policy to ensure that no one slips through the cracks?

We conclude our series on federal disaster policy reforms by focusing on the experience of the most important stakeholders—disasters survivors—and considering how to speed up and maximize individual disaster assistance to provide effective and equitable aid.

We don’t always agree on where the cracks in disaster safety net are

Congress typically expands the pool of resources for disaster aid beyond the appropriations to FEMA’s Disaster Relief Fund based on the number of disasters and their severity. But even then, there are unmet needs that private insurance, personal resources, and public aid do not fill. Though more funding matters, throwing money at problems often does not solve the inconsistencies in eligibility, application, receipt, and timing that cause them.

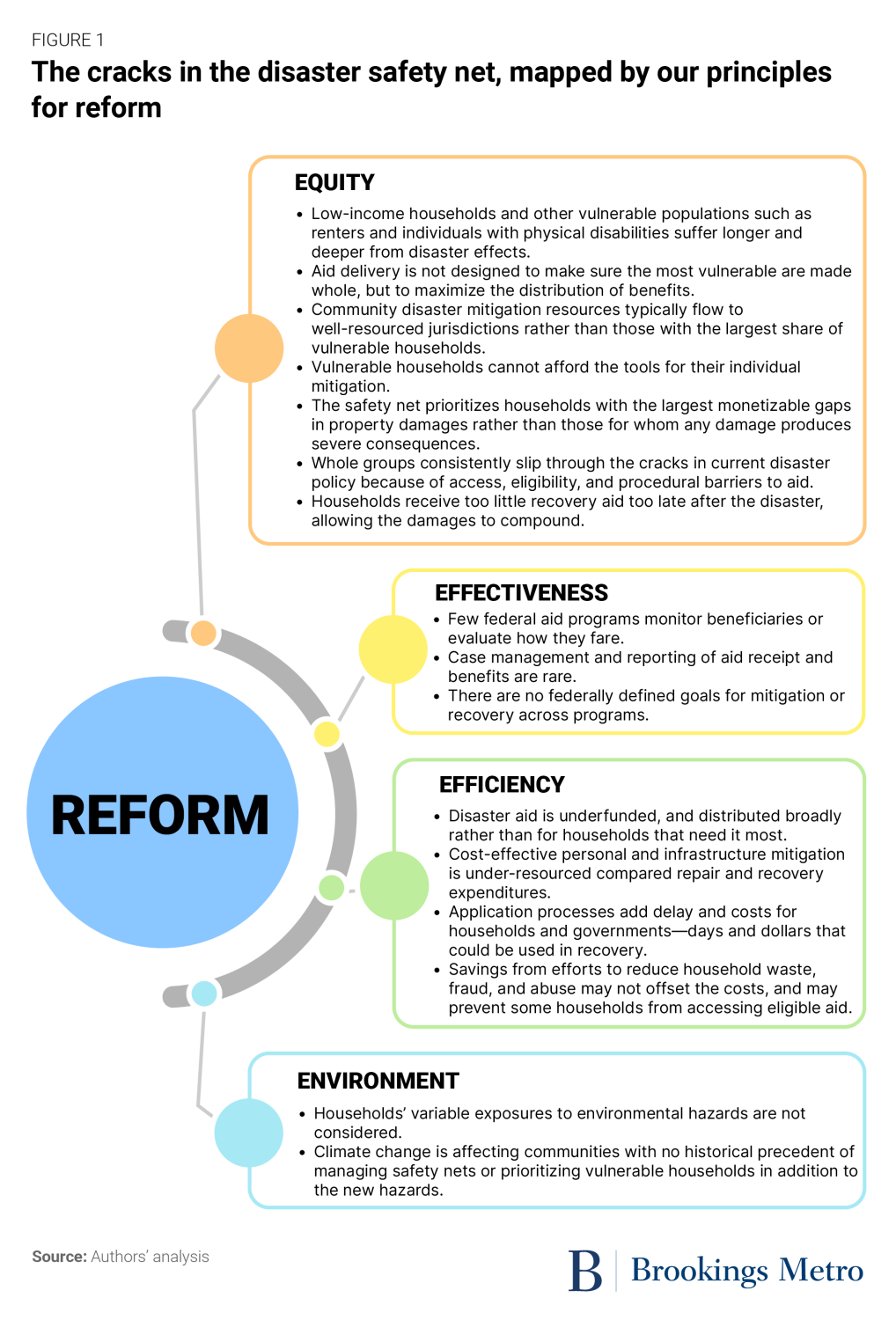

Simply providing more federal money also discourages state governments from investing in hazard mitigation and building the capacity of local disaster functions. Since evidence shows that upper-income households in well-resourced communities benefit most from private insurance and public assistance, more money can also make an inequitable system even more inequitable. Further, debating funding levels obfuscates questions about who we prioritize in the disaster safety net and how their experiences should define how we reform it. Our reform principles in Figure 1 provide insight into how we define the cracks in the disaster safety net.

As agencies share data, we can uncover disparities in disaster protection, relief, and recovery. This data corroborates the media stories: Not everyone is equally exposed to disasters, suffers the same amount during them, or recovers from them to the same degree. Disasters disrupt everyone, but for very low-income households that face a range of financial, social, and environmental vulnerabilities, a disaster can lead to permanent home displacement, job and income loss, downward financial spirals, disruptions in children’s education, ruptures in community networks, and lasting mental and physiological scars—not to mention injury or death. In some cases, these shocks hit the same places and even the same households.

Our current disaster assistance process raises several ethical problems. First, federal policy often aims to distribute assistance as widely as possible. It favors uniformity—standardized helpings of help—over equity. Reasons for that distribution are that there are finite public resources after each disaster, and the government must have a way to spread it out objectively and fairly. However, this way of distributing aid typically neglects the challenges of the most vulnerable residents, who will have a profoundly longer and more painful recovery. We minimally support the many households who are affected over more effectively helping the households who are most negatively impacted.

Second, when we do deliver aid to fill unmet need, we measure that need by monetized damages to property and possessions—not by pre-existing vulnerabilities such as low wealth, lack of housing choice, and limited social capital, which substantially define how these households will fare after a disaster. The dominance of ownership in assessing need also plays out in how we provide pre-disaster mitigation aid, with funds going to places with higher-valued properties whose protection was viewed as more critical.

Third, there is a lag in resource delivery that further disadvantages the most vulnerable. Even when resources are available, they come too long after the disaster event rather than in the immediate aftermath, when additional resources can make the most difference. For example, long-term housing recovery aid often takes over two years to become available to eligible households. By that time, housing-limited families such as renters have either had to find homes nearby (despite limited supply) or they have moved on.

Fourth, the expectation that households can understand aid eligibility, apply for assistance, and provide the necessary documentation for an eventual approval of one program—let alone all of them—is unreasonable. Further, due to a somewhat misdirected concern about waste, fraud, and abuse, too many resources and requirements have been placed on the shoulders of households who have just survived a life-threatening disaster. A growing body of work on government delivery of benefits underscores the pervasive problem of bureaucracy in public aid, while also suggesting how it could be fixed to be more user-centered.

In short, the status quo approach is too poorly targeted, too exclusively focused on property damage, too slow, and involves too many procedures and justifications for the average household, let alone the most vulnerable ones. There are still too many ways anyone—but especially someone with the fewest resources and the most need for a helping hand—can fall into a spiral. Those are the cracks we must fill.

Knowing where the cracks lie is the first step toward filling them

Despite recent attempts by federal agencies to ensure that all households are served, aid programs often have conflicting statutory constraints or program rules that hinder the equitable treatment of survivor households for mitigation before the disaster, relief during, and recovery after. This is where too many obvious cracks lie.

It starts with the challenges of protecting the most vulnerable populations before disasters strike. For some communities, disaster mitigation includes living in places that have protective infrastructure or where there are resources for property-level adaptations such as fireproofing, home elevation, and even buyouts. Research shows that under-resourced and lower-capacity populations are less likely to benefit from and have access to both regional infrastructure and property retrofits. Additionally, communities that are better resourced can competitively apply for mitigation funds. Since much of our mitigation funding is released after a community has experienced a disaster, low-capacity jurisdictions must then make up for multiple disadvantages during the worst of times. Research also shows that lower-income households are less likely to know about household-level mitigation options, let alone have the upfront cash to pay for improvements, the time to wait for reimbursements, or the bandwidth to understand the paperwork.

Disaster mitigation for most households also includes appropriate insurance. Unfortunately, lower-income households are less likely to be able to afford insurance. Access and affordability to insurance diminishes further when considering that these households live in older and potentially less-adequate housing, are renters without housing equity, and may live in locations where exposures are high. When they have the right insurance, insurers’ agents often cannot distinguish between disaster losses and pre-existing conditions. This may lead to lower payouts, if any. There is emerging evidence that low-income households and households of color experience slower claims processing and unsatisfactory claims treatment too.

The cracks widen as disaster strikes and relief programs are launched. Many households turn to FEMA’s Individual Assistance program for immediate help in finding temporary housing, covering expenses, and performing basic repairs to make their homes habitable—needs that private insurance does not always cover. To its credit, FEMA has made great strides toward making the process more accessible by setting up redundant intake centers in survivor communities, providing resources in multiple languages and for a range of individuals with physical disabilities, and creating user-friendly online applications. FEMA has broadened the accepted documentation for proof of land title as well.

Time will tell whether these steps are sufficient. Other onerous requirements for applying for aid, however, have not changed. Applicants must still undergo confusing and sometimes highly inaccurate damage inspections; their cases will be closed if they miss three phone calls, even amid the interrupted service and chaos of post-disaster life; and they can be bounced between FEMA and other federal aid programs. For many families, this round of complicated and confusing application procedures comes after the trials of filing their private insurance claims. Consequently, stories of aid denials and frustrating appeals processes fill local newspapers and community chatrooms. The result is that low-income households and communities of color face higher barriers to accessing disaster relief, even though the payout is generally minimal: FEMA’s Individual Assistance has provided a historical average of $4,270 per household. The most recent data for FY2022 disasters also shows that renters received 22 cents for every $1 that owners received.1

After a household receives FEMA aid, they may be then eligible for the Small Business Administration’s (SBA) loan program. However, SBA disaster loans are directed toward businesses and homeowners, making it particularly regressive. Lower-income homeowners are also denied SBA disaster loans at higher rates. Many households live in under-resourced communities where individual homes or businesses are assessed and purchased at significantly lower values than their equivalents in neighboring wealthier communities. These households are also more likely to have proportionally more debt on their homes and other assets, reducing their chances at SBA loan approvals. SBA loans, then, are a shaky bridge between FEMA’s immediate assistance and other federal recovery aid programs for vulnerable households.

Though a range of other federal safety nets may be redirected toward disaster survivors (such as unemployment assistance and low-income heating and energy assistance), they are typically supplemental. They are also not well coordinated across the federal government. Yet households are required to report all aid resources and prohibited from duplicating benefits across them. The federal obsession with “program integrity”—that is, tracking and eliminating perceived waste, fraud, or abuse within each program—becomes a family nightmare when it is repeated across numerous programs in which requirements and procedures are not aligned. Driven by unfounded rumors of new “welfare queens” who are purportedly milking a disaster safety net, this focus has led to such onerous restrictions and requirements that we are failing to provide help to those most in need of aid—all in the name of preventing program abuse by households, though the rate and severity of household fraud across disasters is unclear. In fact, fraud is more likely to be found among providers of post-disaster services.

By the time longer-term disaster recovery begins, the cracks have become a gaping crevasse through which more households fall. HUD’s Community Development Block Grant Disaster Recovery (CDBG-DR) program is focused on the unmet needs of low- and very low-income households—serving as a backstop to all other aid. In most cases, the income profiles of the ultimate recipients are those the program is designed to serve, but that does not mean that the CDBG-DR-funded programs that states set up are easier to access. Grantees face numerous statutory and program barriers. These intergovernmental exchanges result in bureaucracy and delays for households too. And, of course, CDBG-DR may not always be available after every disaster, since it is subject to special congressional appropriation.

Aid often comes to families years after the original disaster. In many cases, these families have either moved out of their communities or already suffered financial, health, and related losses and have diminished capacity to pursue any aid. Local CDBG-DR programs often recruit applicants who then undergo entirely new application processes—an absurd redundancy. With delays and bureaucracy, many families have given up and moved on with rebuilding their lives, or remain lost and confused in an alphabet soup of program names and applications.

Recommendations for reforming individual disaster assistance

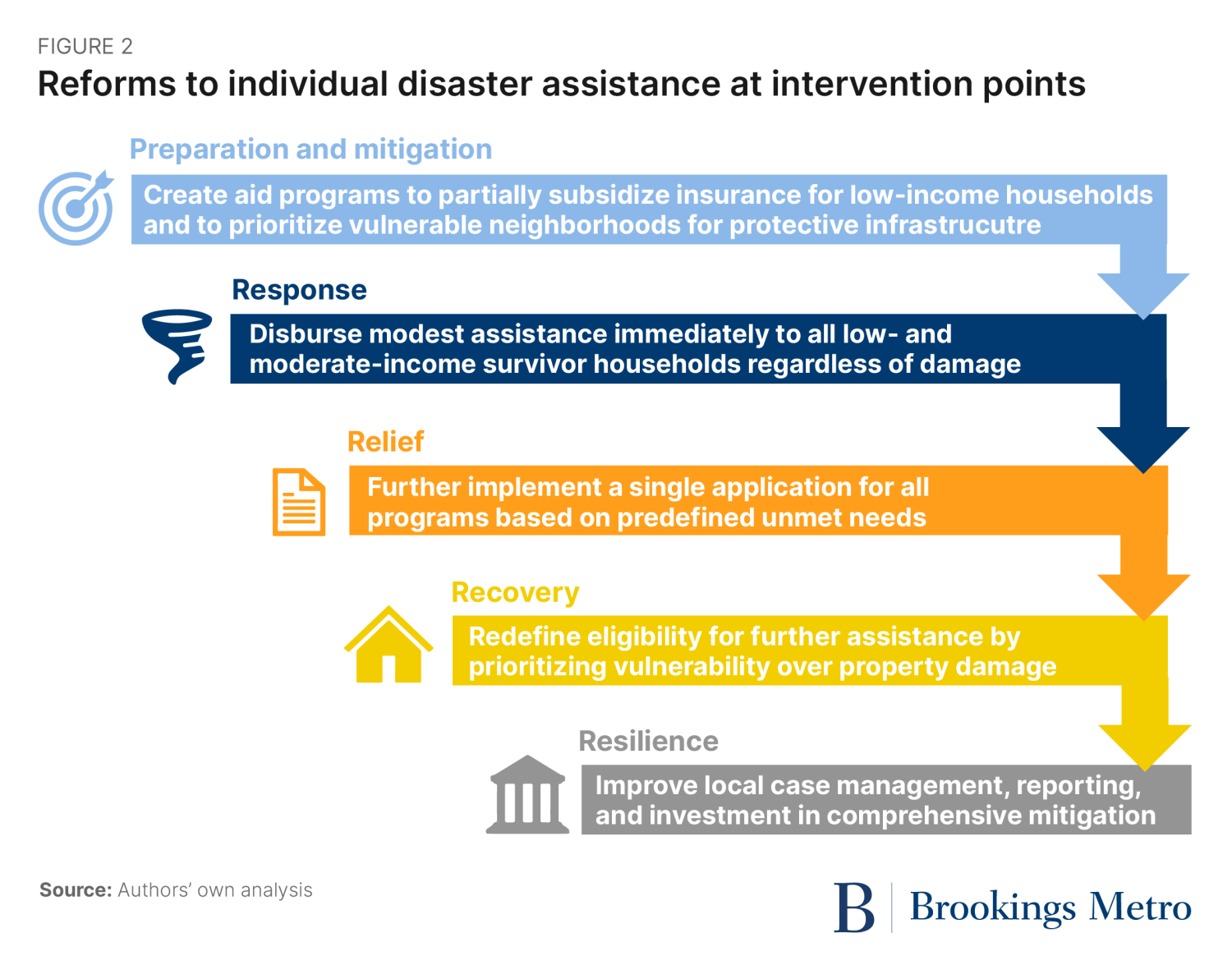

In this section, we recommend a range of policy reforms (depicted visually in Figure 2) that can ensure an approach to individual disaster assistance that serves vulnerable populations, understands their challenges, and prioritizes their outcomes.

First, targeting resources directly to the most vulnerable in all aspects of hazard exposure, relief, and recovery will ensure that social and economic disparities are not exacerbated. This starts with developing a means-tested assistance program to reduce low-income households’ National Flood Insurance Program (NFIP) premiums. This assistance can also come with greater incentives and requirements for property mitigation that reduces the underlying actuarial risk to the program and occupant. Such targeted assistance could also be a model for state insurance pools and insurers of last resort—further ensuring that low-income households are individually covered while reducing physical exposures.

Mitigation of individual properties and possessions should also be matched with increased funding for regional infrastructure that protects whole communities where low-income households live. Programs such as FEMA’s Building Resilient Infrastructure and Communities should expand the award criteria and their current scoring for proposals that prioritize vulnerable households and neighborhoods. Likewise, cost-sharing requirements for Army Corps of Engineers’ projects should be eliminated to produce a more resilient outcome for our most vulnerable neighbors.

Another group of recommendations focuses on streamlining households’ access to and receipt of aid across all programs when a disaster is declared. Should additional household assistance be needed beyond the immediate first payment, households should be able to file a single universal application that identifies all the aid for which they are eligible and pre-approves them, as we have previously suggested and legislators have proposed.

To further reduce the procedural challenges to equitable disaster assistance, the federal government should require a range of state and local government improvements to ensure that these jurisdictions are not only contributing to all their citizens’ well-being, but also prioritizing the most vulnerable households in their own planning and services. Better household case management by state and local partners is a starting point, as is more granular reporting to both the federal government and the public about who receives which aid. Allowing lower state and local government matches for governmental assistance—such as for FEMA’s Public Assistance—when their lower-income communities have disproportionately suffered shows the federal government’s commitment to these households. But it must be combined with additional requirements that state mitigation resources be targeted to these same communities and a threat of reducing federal recovery funding and other federal investments in housing, economic development, transportation, and more should state governments not commit.

We also recommend redefining the eligibility for FEMA and HUD assistance to be more inclusive of increased vulnerability. For the former (which provides aid to all households after insurance claim payments), aid could be apportioned not just by monetized disaster damages but also by a preset income-based scale. Lower-income households, then, would be eligible for a higher share of assistance for the same comparable damage as their wealthier neighbors. CDBG-DR, in turn, could also ensure that the lowest-income households (and especially renters)—whose damages are often very modest—are included in unmet needs calculations and that aid to them comprehensively covers all damages and needs.

The most assertive recommendation regarding direct funds for relief and recovery aid involves providing immediate, modest disbursals of aid to all occupants at or below 80% of the median area income simultaneous to the declaration, regardless of damages and without the submission of a formal request for aid. Two precedents support this transformative approach to aid delivery. First, parametric insurance has proven to be a successful tool for recovery. In these policies, the insurer issues a preset payout to the insured party when a predefined hazard severity is met (e.g., two feet of flooding or a Category 3 hurricane has occurred), without proof of demonstrable loss or claims filing. Upfront payments are clear to all parties before the event, allowing individual families to pay for immediate relief needs and plan for their recovery earlier.

Second, a growing body of evidence shows how the federal government’s three rounds of economic impact payments during the COVID-19 pandemic (ranging from $600 to $1,400 per adult and $500 to $1,400 per child) helped to reduce household suffering, raise families above the poverty line, and boost their financial outlook, in combination with other tools such as eviction moratoria. The federal government’s capacity to deliver this assistance so quickly and comprehensively not only helped these households, but it also proved that government can deliver in times of community distress. Early experiments with this approach, including FEMA’s issuance of advance NFIP payments prior to insurance inspections to Floridians after Hurricane Ian, should be evaluated, but suggest some preliminary benefits.

Strengthening our disaster safety net will help all Americans

In past posts in this series, we discussed several strategies for transforming our national disaster framework to center the most vulnerable households and individuals. We suggested that the very definition of a disaster declaration include the share and depth of pre-disaster vulnerability in a survivor community in addition to the severity of damages.

Current assistance programs are statutorily authorized and funded to improve the lives of survivors by alleviating the costs of preparing for and recovering after disaster—though their approaches have been vastly different in design and, in some cases, they have assisted different types of survivors. Aligning these populations across programs and ensuring that they always include the most vulnerable neighbors in survivor communities is paramount to reforming our disaster safety net.

Like our other safety nets, disaster assistance is a fundamental public function. It benefits the aid recipients directly while keeping our neighbors safe. And improving our neighbors’ outcomes benefits all of us by sustaining local economies, reducing blight, and lowering the costs of other state and national safety net programs that are needed when neighbors slip through the cracks. Ultimately, we are all in this together, during disasters and beyond.

-

Acknowledgements and disclosures

The research included in this report was made possible through funding by the Walmart Foundation. The findings, conclusions, and recommendations presented in this report are those of the authors alone, and do not necessarily reflect the opinions of the Walmart Foundation.

-

Footnotes

- Calculated by authors based on data from OpenFEMA, IHP program for renters and owners. The first amount is averaged over the past 20 years expressed in 2022 dollars; the second is based on FY2022 disasters for which IHP was declared.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).