This is the fifth post in a series on national disaster reforms. Previous posts outlined principles for reform, examined changes to the federal disaster declaration process, recommended improvements in the federal management system, and explored the division of responsibilities between federal and state governments and between the public and other sectors.

It has been a record-breaking year for the number of severe disasters in the United States. This summer started with the Texas hailstorms in May, followed by the nationwide heatwaves in July, and most recently, the catastrophic losses in life and property in Hawaii’s fires and Hurricane Idalia’s Florida landfall in August. The past season has seen so many of these events that our federal disaster relief funds almost ran dry. But there is no such thing as a “disaster season” anymore—if there ever was.

The ongoing suffering that disasters wreak in communities continues year-round, as do the piling costs of their recovery for local governments and the work needed to get ready for the next disaster. There will always be a role and responsibility for states and the federal government to intervene before, during, and after disasters. But local communities are always the first responders—responsible for managing local conditions and ultimately suffering the most from localized disasters.

The question then shifts from who should be managing disasters to who can. Local governments’ financial, knowledge, and leadership resources are often viewed as not or barely capable of managing the intricacies of federal and state funding—gaps that widen in the chaos and turmoil after a disaster.

Federal resources often go to those communities that are most capable of managing them—not those that most need them

All local governments must actively participate in managing their own risks and emergencies and must facilitate their community’s visions for how to prepare for and recover after disasters. Yet challenges at each stage of the disaster continuum—from assessing risks before disaster strikes to understanding federal regulations during recovery—stymie even the largest, most sophisticated, and well-funded local governments.

Federal assistance before or after disaster may indeed be coming, but it might not be disbursed to local units of government because they are judged not ready to “handle” the funds. Local governments’ disaster management capacity is typically defined as the quantity and quality of financial, political, and knowledge resources for providing services to all residents in a few core capabilities such as planning, operations, public information, and direct health and human services. This also includes managing the additional federal or state fund transfers and the slew of other civil and private sector resources that may come. The number and skills of disaster-related staff as well as the budgets of emergency management or local recovery offices are typical indicators of disaster management capacity. Designing innovations in physical and social interventions—such as new protective infrastructure or neighborhood support networks during a disaster—are also signs of high capacity. But while disaster-specific capacity is our focus, we cannot overlook the underlying governmental functions of financial management, household case management, community outreach, and other public functions that will shape disaster management as well.

Based on the state of those functions, there may be good reason for the federal government to be cautious about some local governments. Federal officials are concerned with overwhelming local governments that may not yet have experienced severe disasters, let alone managed transfers of huge sums for disaster mitigation or recovery. Other places with known corruption or ineffective local leadership—some of which are the remnants of historical colonialism, racial segregation, and centuries of disinvestment—might appear as less than solid investments. Further, many local governments lose out in the competition for talent against their larger, better resourced peers, leaving them with a skeletal staff with limited experience and aspiration to innovate.

Aside from the measurable conditions in these jurisdictions, the definition of “capacity” is often politically subjective and manipulated—for example, by gatekeepers in state governments that may be at odds with the leadership of particular counties and cities. In just the past few years, there have been well-documented cases of state officials withholding funds to local governments for needed infrastructure improvements as well as disaster recovery.

Compounding that, some localities with weak fiscal bases have limited resources for disaster mitigation and recovery offices or have other non-hazard-related emergencies or funding priorities that have depleted them. Some cities simply have not had to think about disaster management capacity because they had little experience to suggest they would have to.

Research is inconclusive about which unit of government disperses funds to their communities and residents most efficiently. But competent, capable, and coordinated governments at all levels clearly drive better disaster preparedness and resilience outcomes. The Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA), Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD), and other federal agencies involved in disaster management—from mitigation through recovery—have implemented multiple strategies over the years to improve local government capabilities. Yet the federal government must continue to do everything within its statutory authority to build the capacity of local governments across the board, especially ones that are physically distant from the centers of financial, political, and intellectual capital such as tribal, rural, and underserved urban jurisdictions.

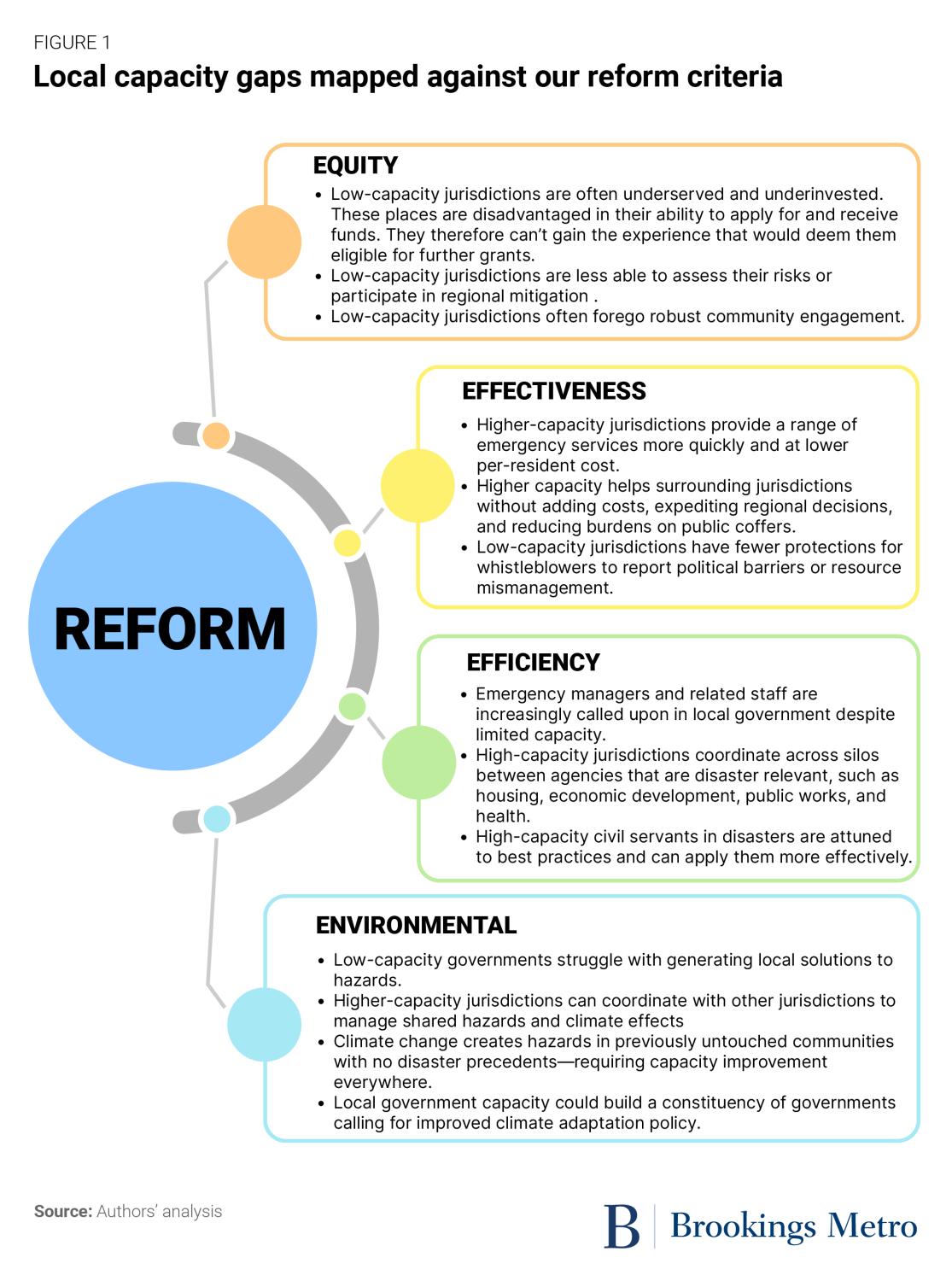

Further, more accountable local capacity-building is a fundamental component of a principled reform of national disaster policy. But knowing what local capacity is—and how to build it—are still works in progress. High local government capacity is a critical piece for meeting the goal of national disaster policy reform. The current state of entrenched low capacity in several local jurisdictions presents multiple barriers to the transformation of federal disaster activities that could meet our principles of equity, efficiency, effectiveness, and the inclusion of environmental change (see Figure 1).

We lack standard definitions for local operational capacity and rigorous ways of assessing it

Federal agencies have grappled with the challenge of defining and assessing local operational capacity in nearly every public service area, not just emergency management. Our compliance-driven approach to government functions limits federal definitions and measures of local capacity to indicators of grant implementation, such as financial reporting, regulatory compliance, and contract documentation. The focus on “program integrity” to minimize waste, fraud, and abuse overlooks opportunities to encourage and reward localities’ creative outputs as well as more socially and environmentally meaningful outcomes.

However, more robust and deeper thinking about local capacity suggests that underlying resources determine whether local governments can access grant programs and then produce the kind of compliance outputs that federal programs expect. Financial resources in the form of tax, permitting, transfers, or other fee revenue clearly are central to a jurisdiction’s ability to hire, train, and promote competent staff. They also enable localities to acquire and maintain modern management information systems and citizen communications. There are proxies for defining those aspects of local government capacity, including: fiscal capacity; disaster-specific expenditures; full-time employee counts and churns; individual employee skills and certifications; the number and roles of external consultants or contractors for disaster-related functions; and even the content of job postings, which provide useful, albeit partial, insight into local government hiring.

Yet financial resources are not the only enabling factor. Knowledge resources such as the surrounding intellectual capital in a jurisdiction (including active private, civil, and academic sectors), residents’ civic engagement, governance flexibility, the strength of managerial institutions, ethical leadership, and political will are also critical factors. Knowledge resources are an especially important contributor for jurisdictions to successfully apply for grants to begin with—i.e., having internal expertise within the civil service rather than contracted out, and then using grant resources creatively, with the most recent best practices and evidence base, and with the potential for leveraging the funds.

Not surprisingly, perhaps, federal and state governments have refrained from objectively and transparently measuring these sensitive indicators of local capacity. So, the rules remain largely unwritten for the jurisdictions that succeed in their applications for competitive grants or those that are less likely to be intensely scrutinized in the execution of their formula grants. There is considerable discretion and much subjective judgment-making. Under these rules, high-capacity jurisdictions continue to benefit, and purportedly low-capacity ones continue to be at a disadvantage in securing federal funding. This has increased the potential for politicization of grant eligibility and awards, especially where a state government can preempt local jurisdictions to unfair effect—such as in the recent case between the state of Texas and Harris County over Community Development Block Grant Disaster Recovery (CDBG-DR) allocations. It has also obscured the ability to assess which level of government (federal, state, county, city, or otherwise) and which characteristics can best serve their citizenry.

For disaster management, low local capacity can mean the difference between life or death—literally. So, to lift all boats, federal agencies have attempted to provide guidance, instruction, and in some cases, staff and expertise to jurisdictions.

Federal agencies have struggled with when and where to assess and build local capacity

Typically, federal agencies only assess capacity for current federal grantees. And based on a traditional definition of capacity, resulting technical assistance (TA) has primarily focused on conformity to grant terms rather than a more robust building of fundamental capacity factors that public management literature has identified. This is especially true for disaster recovery functions, with agencies offering TA only after a jurisdiction’s capacity is hampered following a hazard event.

Smaller jurisdictions—especially rural and tribal governments—are at a particular disadvantage. For example, HUD only awards CDBG-DR grants to CDBG entitlement jurisdictions. Some rural counties and tribal governments submit hazard mitigation plans that provide some information about capacity. FEMA has subsequently provided TA to local governments, including tribes, on submission templates. However, jurisdictions have tended to rely on outside consultants when they cannot absorb new staff for short-term funds—missing the opportunity to expand the expertise of local staff.

Direct TA for potential applicants—not just existing grantees—is a relatively new point of federal intervention. Disaster-related agencies such as FEMA have followed suit. Through the Building Resilient Infrastructure and Communities (BRIC) competitive grant program, for example, FEMA has adopted the models of other agencies by providing pre-award technical assistance because of the number of local jurisdictions that had requested help for risk identification as well as plan and project development. Moreover, FEMA prioritized traditionally disadvantaged local governments for this TA.

But we need deeper resources for more communities. We also need a neutral, consistent way to assess both capacity that is specific to disaster management and in other key functions that define local disaster operations, and in a way that is transparent enough to ascribe appropriate resources but sensitive enough to not penalize or draw unfair public perception to capacity gaps that exist due to causes beyond a local government’s control. Then, we need to seed high-quality capacity with expertise where it is most needed.

States and high-capacity cities that have become skilled disaster grant administrators had to go through their own learning curves. Capacity can be built. And the following sections recommend how.

The first step forward for federal disaster programs is to learn from and partner with other federal agencies that assess local capacity

Numerous agencies across the federal government have information that is pertinent not only to federal disaster programs, but for any place-based intervention that falls under federal investments. This is especially true for agencies such as HUD, the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), and the Department of Transportation (DOT)—and there is much they can share with agencies such as FEMA.

Standardizing local assessments will not only ensure that similar capacity limitations are identified, but it can also ensure that federal resources for TA are more efficiently distributed and not duplicated. The White House Office of Management and Budget could lead an interagency working group to make progress on measuring and improving capacity and sustain cross-agency learning and better coordination over time.

Second, there should be more robust and more frequent assessments of local governments’ disaster management capacity

Federal agencies directly involved in local disaster functions—such as FEMA, the Small Business Administration, and HUD—should create a standard and statutory set of assessment criteria. But these should be cross-walked with the criteria from other federal agencies that might bear on relevant local functions shaping disaster management capacity, such as financial accounting. Though many federal agencies acknowledge that the days of checking boxes for grant compliance should be a thing of the past, they are often statutorily limited on what information they can gather, are obliged by their auditors and general counsels to stick with compliance monitoring, or are simply in the dark about what information could be collected and how. In some cases, evidence of strong or improving capacity from one federal agency should count for their potential capacity for disaster-related federal funding.

One critical omission in local capacity assessments to date has been the sole focus on governmental agents, though local civil and private sectors do not just provide critical disaster-related services. These sectors also help define—and in some cases, raise—regional intellectual and professional capital. For example, Volunteer Organizations Active in Disasters (VOADs) have historically coordinated with local governments, but that depth of coordination is not fully assessed as part of that governments’ capacity.

A regularly timed assessment of local disaster management capacity that can also be coordinated across federal agencies will require time and resources. The assessment should not overly burden or overwhelm local governments with limited resources. But too infrequent of an assessment will also not provide timely information for distributing TA or assessing changes from factors such as local political transitions or from the TA itself. A four-year cycle may be an appropriate starting point.

Third, this sensitive information should be treated with care to avoid unintended consequences that could result from public dissemination

Public dissemination of sensitive assessment information could result in lowering capacity further in these places. Capacity assessments should avoid identifying individual staff, for example. More profoundly, however, is the potential that public knowledge of capacity gaps could result in external effects such as reduced private property values or damaged municipal bond ratings. Consequently, synthesizing information for public transparency akin to local compliance with federal water and air quality standards could be encouraged.

But before the release of that information, providing TA as well as broader financial resources where there are clear gaps could avoid unfair repercussions and let jurisdictions prove themselves. The federal government has typically held low-capacity local governments to the same standards as high-capacity ones and state governments that have managed funds for decades. So, providing direct TA based on objective measures could rise the tide. It could also avoid further penalizing low-capacity jurisdictions before they need to prove themselves.

Fourth, federal agencies charged with disaster-related responsibilities should provide more money for better-quality TA and distribute the costs and benefits more fairly

A first step toward better TA is more and better directed federal funding. TA should be accessible before grant applications are being prepared and across the range of capacity gaps that exist—both disaster-related and for deeper operational capacity across local governments. This includes providing higher-capacity engineers, social workers, logistics experts, and related professionals, paired with trained instructors and community engagement professionals to help communities devise their own creative solutions to risks and recovery.

A range of strategies have been tested for several decades in the federal government, such as HUD’s Strong Cities, Strong Communities program and the Forest Service’s Community Wildfire Defense Grants. Current pilots include the Thriving Communities TA programs across the DOT, HUD, and EPA. Experiments for innovative TA have occurred in the disaster space via public-civil partnerships, including HUD’s Rebuild by Design and the National Disaster Resilience Competition’s Resilience Academies. Along with BRIC’s current pre-grant assistance, there is a wealth of knowledge to be gained. It just needs to be extended to the range of local governments and monitored to ensure capacity has been built after all.

But most rural, tribal, and disadvantaged urban communities are still underserved by these efforts, and their underlying challenges in accessing premier expertise and consultation remain. Teaming up with their regional neighbors might draw a bigger pool and could be more cost-effective for federal TA programs.

Fifth, federal disaster programs should require more state, regional, and county governments to have skin in the game

For federal TA, state governments should commit financial resources and leadership for local governments under their wings. Such collaboration could be incentivized as part of a broader disaster policy reform in which states receive a lower deductible for federal relief and response assistance in exchange for co-funding capacity-building in their most struggling jurisdictions. States could receive higher block grant funds for either supporting federal TA within their jurisdictions or creating their own local TA programs (such as California and North Carolina are currently experimenting with), but would also face reduced funds for not supporting them.

Still, small cities, towns, and tribes should have the ability to circumvent state government bottlenecks to access federal TA when necessary. Regional collaborations among these communities could result in agreements for a jurisdiction’s improvement needs and shared steps between various levels of government.

Finally, the federal government must track outcomes in local governments that have been assessed and received federal TA

Measuring whether federal TA has been effective and the resulting capacity makes a difference not just in fiscal and regulatory compliance, but also in actual disaster outcomes and other measures of community governance, and self-sufficiency must be a priority. Evaluating TA is complicated, but there are ample opportunities given the increased quantity of recent TA efforts (such as BRIC’s) as well as the number of applicants across the range of TA access and eventual award statuses.

Ultimately, all this capacity assessment and capacity-building must focus on long-term outcomes and be linked to a patient vision for change. Many communities have suffered from centuries of disinvestment. Penalizing them further—beyond the withholding of funds that they already suffer—is not going to make them improve overnight. If, per the adage, teaching someone to fish is more just and practical than handing them fish, then the federal government, working together with states, should at least ensure that lower-capacity jurisdictions get their fishing poles.

As climate change increases disaster exposures across more places in the U.S., building the local public sector is fundamental. And it must be done now, otherwise there will be more waste, fewer protections and assistance, and more suffering.

-

Acknowledgements and disclosures

The research included in this report was made possible through funding by the Walmart Foundation. The findings, conclusions, and recommendations presented in this report are those of the authors alone, and do not necessarily reflect the opinions of the Walmart Foundation.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).